The World Of Mad Max Isn't A Junkyard, It's An Art Gallery

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Mad Max: Fury Road" is one of the greatest films of all time because of its specificity. Other films would be content to have great action sequences, striking visual design and an exciting narrative that riffs on second wave feminism. Masterpieces have been made with less. But the cast and crew of "Fury Road" wanted something more than a great film. They wanted to create a world that felt distinct, that had a sense of texture, history and depth. Creating this world took years of work, the dedicated labor of many smart and talented individuals, and an expense of nearly two hundred million dollars. Thankfully, they pulled it off.

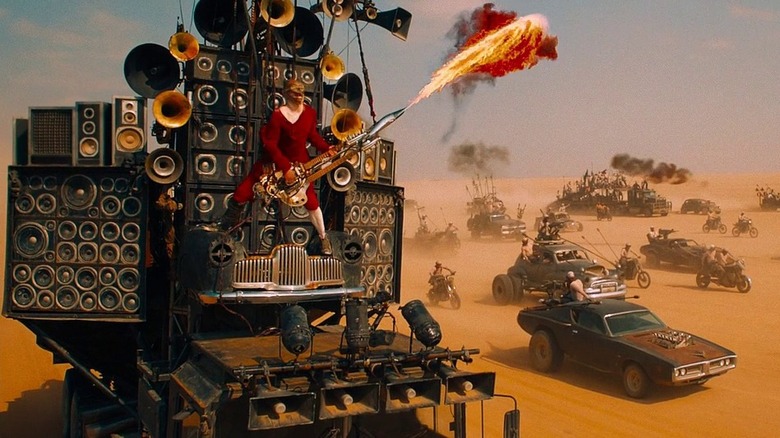

A massive spiked tanker truck. A bird skull bobbing on a spring. A fire-spitting guitar. Mention these to a fan of "Fury Road" and they will recite the names and context of each prop with the intensity that accompanies religious scripture. These props are as important to the film as the actors, because they are characters themselves. In the recently published oral history "Blood, Sweat & Chrome: The Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road," journalist Kyle Buchanan interviews several members of the "Fury Road" crew. In the process, he uncovers what any fan of the movie may have suspected from repeated rewatches and close attention. If every object in the world of "Fury Road" appears to have a story of its own, that is because they were designed that way.

'We found things that we thought were beautiful enough to salvage'

The world of "Fury Road" was forged from junk. By command of George Miller, "everything has to be created out of found objects repurposed." To this purpose, the crew bought, stripped and retrofitted used cars. They cut the heads off dolls and turned them into steering wheels. They paid daily visits to "the boneyard," a nearby junkheap loaded with objects ripe for the taking. "We found things that we thought were beautiful enough to salvage," said production designer Colin Gibson. "Or at least...to think, I wonder what it was?" The props of "Fury Road" were not just built, but discovered. Each a rescue in spirit from obscurity in the wastelands. Sometimes they were repurposed, often transformed, but at the center of each prop was some mysterious object that caught the eye.

The crew of "Fury Road" were as concerned with function as form. The harshness of the film's universe demanded economy and ease of use. On set, Gibson requested that each prop have three or more functions. In "Blood, Sweat & Chrome," salvage artist Matt Boug brings up a tool kit used in the film as an example. The tool kit comes with a crowbar, which can be used to remove a tire as well as bludgeon somebody over the head. But the crowbar is also cross-shaped, and thus a religious icon. Tool, weapon and fetish. The crowbar fulfills each of these functions, and therefore develops three-dimensionality.

The guitar of Theseus

The Doof Warrior's guitar presents a fantastic example of the dangers of form over function. Pieced together from a porcelain bedpan and a french horn, the result greatly impressed George Miller. But then he asked the fateful question: "Does it play?" The crew had thought carefully about how the guitar would look, and they'd done the work to ensure that it would spit fire on command. Yet they found themselves rushing at the last second to break apart their work and reassemble it around an actual guitar. The final result was workable, but so heavy that they had to add a bungee cord to the set to provide the Doof Warrior with support. According to Australian singer iOTA, the Doof Warrior himself, "It is the shittiest guitar I've ever had the misfortune to have hanging in front of me."

The secret sauce that made "Mad Max: Fury Road" is the genuine respect for the film's world and its people. The crew of "Fury Road" did not simply strive to pack the movie with cool objects. They thought about whether the prop was convenient or inconvenient to use and what that said about the person who owned or inherited it. They took the lives and psychologies of the film's characters seriously, even when those characters were named things like "The Bullet Farmer" or "Toast the Knowing." Best of all, they thought through how these characters might express themselves through the objects surrounding them. For the reclusive Vuvalini, a team of older warrior women, Boug developed a fuel tank cover made of knitted electrical wire. It could be used as protection, but also functioned as a kind of tea cozy for machines.

I'm gonna die historic on the Fury Road

In an interview with the Guardian in 2015, George Miller confirmed that despite the harshness of "Fury Road," art and self-expression does exist within its universe. "If you look at all human culture, no matter how impoverished the circumstances, it doesn't mean that there's not a strong aesthetic," he says. He expresses a similar sentiment in the "Blood, Sweat and Chrome" book, "Just because it's the wasteland, it doesn't mean that people can't make beautiful things." In other words, people are people regardless of their surroundings. For this reason, the film's style and art direction is not simply affect but instead a direct expression of the characters and their psychology.

At this point you may be asking yourself, "If this is the right way to do things, why doesn't every movie take this route?" What does "Fury Road" have that most modern blockbusters simply do not? Money and talent are two possible explanations, but I think the correct answer is time. Due to a series of costly disasters, "Fury Road" took over a decade to make. This caused enormous stress to the cast and crew, and it worked the executives at Warner Bros. into a froth. But it was this protracted production schedule that allowed the crew to flesh out the world of "Fury Road" to such a degree. The characters evolved, their cultures were developed and reworked, the designs were iterated again and again. The final results were undeniable, but only because the artists had managed to stump the executives every step of the way.

The props of "Fury Road" may have been short-lived art, produced only to be destroyed at the film's end. But in the arc of their short lives, the fire is unmistakable. They represent a freak accident in the course of film history that may never be repeated, even were the same cast and crew to reassemble. Each of us in our own way may carry the lesson forward, that in the awful heat and cold of the desert there are people who might build things for the joy of it.