John Hughes Wrote A National Lampoon Article That Launched His Career

Long before he was entertaining audiences with "The Breakfast Club" and "Planes Trains and Automobiles," John Hughes was a staff writer for one of the most chaotic American counter-cultural (if you can call a Harvard humor magazine spin-off such) outlets of the 21st century. "National Lampoon" magazine, during its run from 1970-1998, traded in bawdy jokes and stinging parody, and no subject was safe. As former "Lampoon" editor Tony Hendra says in the documentary "Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon": "It is the job of a satirist to make people in power uncomfortable." So they did, with social relevance and outrageous comedy in equal measure.

Hughes came onto the parody writing scene during the "Me" decade. "Lampoon" editor P.J. O'Rourke recalled in The Daily Beast:

I met him in the mid-1970s when he was the youngest vice president ever at Leo Burnett and — for the Ferris Bueller of it — was writing freelance articles in the National Lampoon. I was an editor there. John wrote so fast and so well that it was hard for a monthly magazine to keep up with him.

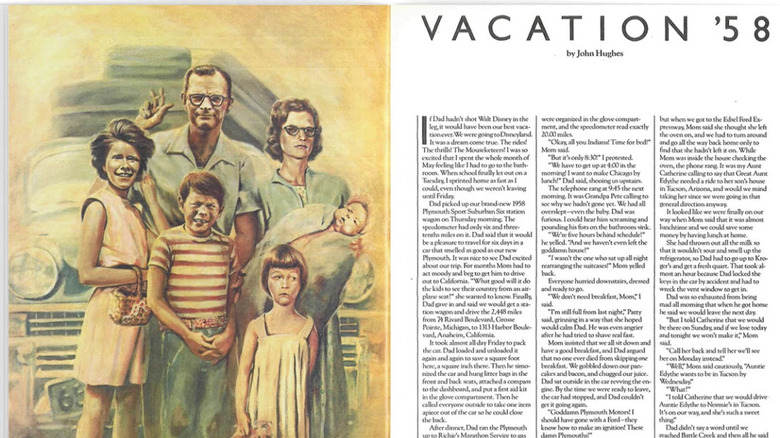

The 1979 issue of "National Lampoon" published the one-day filmmaker's fictional account of a disastrous road trip with his beloved family, and The Hollywood Reporter has reprinted it for your reading pleasure.

'If Dad hadn't shot Walt Disney in the leg, it would've been our best vacation ever.'

Like many great works of literature, "Vacation '58" was borne of isolation and desperation. John Hughes had a 9-to-5 writing advertising copy at ad agencies when this story came about, and a furious Chicago blizzard provided the conditions for Hughes to write — he was snowed in, and simply couldn't leave for a few days. And thank goodness for that.

The story itself is a bundle of familial dysfunctions and absurdities, fully believable to anyone who has been on a road trip with loved ones across the American landscape. The fictional child of the tale recalls the meticulous preparations to pack the family's new '58 Plymouth Sport station wagon for the arduous drive from Grosse Pointe, Michigan to the Happiest Place on Earth. Humor is found in the father's intensely poor emotional management (he sits in the idling car pouting in the driveway while the family eats breakfast after everyone — including him — overslept on travel day) and the underwhelming tour of the nation ("There was absolutely nothing to do but stare out the window at the moonlit fields of corn."). Set during a time when "Father Knows Best" was dominating the CBS ratings, Hughes' story poked fun (as National Lampoon is wont to do) at the sacred cow of the traditional, "ideal" American family while maintaining admiration for their messed-up dynamics.

'Sorry, folks! Park's closed.'

It's an especially fascinating tale to read at the dawn of the Reagan era, when the Republican president would try to make good on his campaign slogan ("Let's Make America Great Again!") and call for a return to a simpler time (for white dudes), when, as Archie Bunker wailed in the "All in the Family" theme, "Girls were girls and men were men." The fall issue containing Hughes' story alongside a parodic Norman Rockwell-esque portrait would publish just months after then-president Jimmy Carter reported on a "crisis of confidence" from the American people in a nationally televised address to the people.

As in most of Hughes' later films, the family sat at the center — warts and all. As Hughes' lil' scamp would observe in the essay, Dad made all of the preparations and acted as the family leader, but his ineptness popped up just as often as his most competent moments. But the essay is just as much a product of its time: an unfortunate passage highlights the family's journey past an indigenous people's reservation, where they are held at gunpoint and accosted by stereotypically drunken Native Americans. Considering the button-pushing humor that the Lampoon works have long championed in print, on stage, and on screen, these pitfalls are impossible to avoid when revisiting or evaluating any of their eras. Refusing to stop along any diminishing lines of common decency, Hughes plows forward, culminating in dear old Dad's cheese sliding off his cracker upon learning that Disneyland ... is closed for repairs. He snaps, and the climactic incident is a dangerous, goofy reckoning for Walt Disney himself. Though he rarely spoke about politics in public, Hughes' fun-making still holds a reverence for family — albeit one whose lack of polish and perfection add to their humor and charm.

Sound familiar?

While reading "Vacation '58," dedicated National Lampoon fans will easily spot the bits and bobs (Dad named Clark falling asleep at the wheel, giving an elder Aunt a ride that ends in ridiculous tragedy, visiting country bumpkin cousins, etc.) that would later build the foundations of the 1983 comedy "National Lampoon's Vacation," which Hughes would also write. Under the direction of Second City alumni Harold Ramis (who would go on to pen and star in "Ghostbusters" the following year), "Vacation" followed the misadventures of the Griswold family on their cross-country journey to the Walley World theme park in California. It's an infinitely quotable film, and one that still has enough purchase to inspire a revival series (though we haven't heard anything on it since 2019).

Since the magazine's launch in 1970, "National Lampoon" has brought forth far-reaching comedy in nearly every medium in addition to advancing the careers of scores of comedy luminaries. From the "Vacation" springboard, John Hughes leapt into Hollywood and stood at the helm of over a decade's worth of successful, timeless live-action comedy films. Remember that when you're writing that story during quarantine.