We Need To Stop Romanticizing The Tortured Batman Actors Narrative

Whenever a new Batman film is released, we expect to hear certain things during the promotional trail. We want to know what it's like to wear the Batsuit and do the growling voice. We get into arguments over who the best actor to play the role is and which version of Gotham City intrigues us the most. Most of it is fun and games, nothing too different from the usual spiels of a movie's marketing cycle. With Batman films, however, there is a darker streak to the narrative that rears it ugly head every single time. As we neared the premiere of "The Batman," starring Robert Pattinson in the title role, some familiar headlines began to spring up.

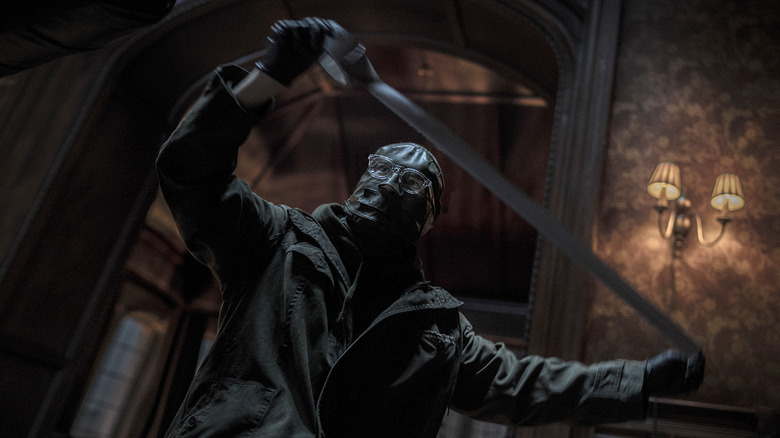

Paul Dano was asked about his process for getting into character as the Riddler, and articles offered dramatic headlines that turned his work into something scary, almost torturous. He creeped out director Matt Reeves with his prep, headlines screamed. He "looked into certain serial killer things" for inspiration. Mostly, it was noted how Dano admitted he had trouble sleeping because of the intensity of the character. A lot of this seems rather standard for an actor playing a dark role, and this film's iteration of the Riddler is certainly a bleak one. It was less the actor's own descriptions of his work that proved discomfiting than how the media immediately latched onto it as something to simultaneously laud and leer at.

Check out any reporting of Batman productions of the past 15 years or so and you'll see a hell of a lot of coverage with this strange focus and tone. More than any other superhero franchise there's something about Batman that has led to this peculiar myth-making regarding how these stories are told and the supposed damage it inflicts upon its participants. It seems as though we are obligated to gawk over the ways that actors have apparently put themselves through hell to play characters from comic books initially intended for kids: Christian Bale's intense bulking up for the Dark Knight trilogy; Jared Leto's carnival of faux-method nonsense, including sending his co-stars dead animals, to get into the mindset of the Joker in "Suicide Squad" (and early reports of the "tormented" actors for that film having a therapist on standby because of its supposed darkness); the drastic weight loss of Joaquin Phoenix for "Joker" and claims he tapped into his own tragic past for the part; and, of course, the death of Heath Ledger being consistently connected to his rumored seriousness over playing the Joker in "The Dark Knight."

The fallacy of becoming the Joker

It's tough to talk about this problem without talking about the premature passing of Heath Ledger, who died in 2008 at the age of 27 from an accidental drug overdose. He would receive a posthumous Oscar for his performance as the Joker, an undeniable tour de force that helped to radically redefine the character for a new generation of Gotham lore. Yet, arguably more than the work, what has come to define Ledger since his death is the way he died and the tenuous connection it held to his prep for playing the Joker. Much was made about how he lived alone in a hotel room for a month and kept an extensive diary to formulate the Joker from the ground up. Rumors started spreading that Ledger was stridently in-character at all times on set, that he found it difficult to get out of the Joker mindset for months after the shoot, leading to drug use. None of this was true. His co-stars refuted such claims many times and noted how Ledger was friendly and charming to work with. Yet the myth was so morbidly appealing — this notion that a man could be so dedicated to the darkness of his craft that he gave up his life for it — that it took root in the public imagination. No matter how much we try to correct the lies, and no matter how deeply exploitative this take on addiction is, Ledger's life and career seem permanently tied to this agony. It cannot help but feel like an insult to his legacy on some level.

It's not just Ledger, of course. Leto's antics for "Suicide Squad" were so uncomfortable that they became parodic, a total bastardizing of what method acting actually is. At times, his "in-character actions," like sending used anal beads to co-stars, were less the actions of a dedicated actor and more an example of workplace harassment. Indeed, these stunts felt just like that in the end, a matter not helped by the harried attempts to change the film's tone to something more frenetic and humor-driven in the reshoots. All those reports of actors feeling overwhelmed by the darkness of the story suddenly dissipated when the new trailers had neon graffiti overlays and pop music blaring off the screen.

So much of the marketing and awards campaigns for "Joker" were obsessively centered on Joaquin Phoenix's supposed physical and mental trauma, with many critics trying to draw parallels between the character and Phoenix's own loss following the death of his brother. The notion of losing around 52 pounds in mere weeks through a borderline starvation diet was wildly fetishized as a symbol of artistic dedication, even as Phoenix described the process in extremely questionable terms that set off alarm bells for anyone with experiences with disordered eating. With both films, Warner Bros. seemed keen to emphasize the actors' commitment beyond the call of duty or common sense. They keenly understood how it benefitted them to make those narratives work, both for commercial and critical purposes. It certainly worked for "Joker," a billion-dollar hit that won two Oscars out of 10 nominations.

Praise be to Robert Pattinson

None of this is exclusive to Batman cinema. We could be here all day listing the ludicrous ways that actors have gotten into character for films, whether it's Leonardo DiCaprio eating raw bison liver for "The Revenant" or Daniel Day-Lewis demanding to be spoon-fed while playing a disabled man in "My Left Foot." There's a long and dubious tradition of male actors utilizing (or completely bastardizing) the method to mythologize themselves in the pursuit of actorly acclaim. Christian Bale, an actor known for going deep and physically torturous for his films, once described his job as being "very sissy," so what better way to combat that than to commit to it in such brutally macho terms that acting suddenly feels dangerous?

For thousands of years, it's been seen as not only expected but preferred for artists in all forms to truly suffer in the name of their work. Batman has attracted this mindset more than, say, Iron Man or Captain America, because of the emotional darkness of the source material. Gotham is a grimy world centered on a traumatized orphan with regular dealings at a mental hospital. Of course the actors would want to go dark for that, right? But it's not healthy or even especially interesting for us to perpetuate this idea. To insist that only those who have truly suffered can accurately convey it is mentally damaging and also just unfair to the creators doing the work. As Laurence Olivier was famously quoted as once saying, "have you tried acting, my dear? It's so much easier."

Praise be to Robert Pattinson, a semi-trolling leading man of immense self-awareness who has uniformly rejected this narrative. A man who admits to lying through most of his interviews just to keep himself entertained, Pattinson has avoided playing up the tortured Batman image, even as he plays a version of Bruce Wayne who is damaged to the point of ceaseless self-loathing. "The Batman" is an excellent film and its performances are allowed to stand on their own two feet, not bolstered by fraudulent narratives about how the actors engaged in acts of borderline torture for your entertainment.