Mulholland Drive Ending Explained: The False Promise Of Hollywood

The original DVD of David Lynch's Oscar-nominated 2001 film "Mulholland Drive" included an insert that offered viewers a series of clues as to how one might interpret and decipher some of the more surreal aspects of the film. It had 10 steps, which I present here fully transcribed, because they are bloody fascinating:

- Pay particular attention in the beginning of the film: At least two clues are revealed before the credits.

- Notice appearances of the red lampshade.

- Can you hear the title of the film that Adam Kesher is auditioning actresses for? Is it mentioned again?

- An accident is a terrible event — notice the location of the accident.

- Who gives a key, and why?

- Notice the robe, the ashtray, the coffee cup.

- What is felt, realized and gathered at the Club Silencio?

- Did talent alone help Camilla?

- Note the occurrences surrounding the man behind Winkie's.

- Where is Aunt Ruth?

The language definitely sounds like David Lynch, who tends to describe his own films with brief, pat axioms; Lynch described "Eraserhead" as "a dream of dark and troubling things," while "Inland Empire" was summed up as "A woman in trouble." But giving a list of clues about his films is markedly out-of-character for Lynch, who has been openly reluctant to discuss such details as "meaning" and "symbolism" in his films. Lynch has said in interviews that the film is all that was needed; everything a viewer needed to know was already presented in tact up on the screen. Further discussion could only be a watered down version of what he already did. This is why no home video releases of Lynch's film contain commentary tracks. Don't talk over the movie. Just watch it.

Thankfully, going down Lynch's list of clues is maybe one of the least helpful approaches to "Mulholland Drive," which Lynch described as "a love story in the city of dreams." When looking for two clues before the credits, one can only postulate what Lynch might be getting at. A robe, an ashtray, and a coffee cup don't necessarily highlight any plot details. Clue #4 might reveal that Lynch is just toying with us: The accident in question takes place on Mulholland Dr. That's the name of the movie!

Should we be doing this?

Given Lynch's propensity for deliberate obfuscation, is it even proper to offer an explanation of his films' endings? Surely watching the nightmarish psychological labyrinth of "Mulholland Drive," and being deeply lost in a mystery that is not meant to be escaped is a powerful enough emotional experience to lure in a casual viewer. Perhaps, then, we can call it a cognitive exercise or a literary experiment in order to discuss what Lynch would prefer we not. Or we can throw propriety to the wind, and just have a little fun. Let's take a shot of espresso and dive in.

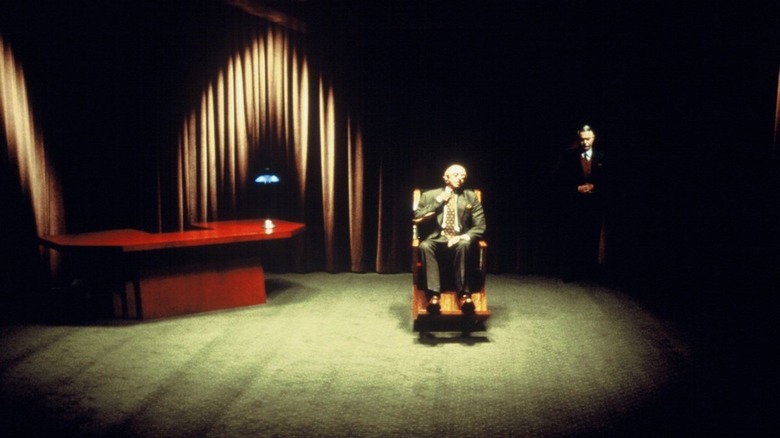

"Mulholland Drive" is, to this critic's eye, a kind of a love/hate letter to Los Angeles, and to the film industry in particular. J. Hoberman in The Village Voice called it a poisonous Valentine. Many scenes early in "Mulholland Drive" take place at film studios, in board rooms, or in the home of a Hollywood director, and these scenes are tense, horrifying, threatening. When the director character Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) takes a meeting with one of the studio's executives (composer Angelo Badalamenti), the executive spits out his subpar espresso onto a napkin, inciting his wrath and insisting on a casting change to the film Kesher is working on. Another studio toady is later seen in a dark, mysterious space talking to an unnamed man (actor Michael Anderson in an outside body suit) who issues casting decrees with single-word codes.

An artist like David Lynch has likely taken plenty of meetings with studio heads and executive mucketymucks who have, no doubt, asked him why he has made the artistic decisions he has made, and wondered if could he perhaps tweak it a little bit to make it more bankable please? One can't help but postulate that these ineffable studio meetings wherein sinister characters hate coffee and issue creative decrees through a byzantine series of bizarre passwords, and who are driven by unknowable motivations, are David Lynch's view of the Hollywood studio system. Although the Kesher character does not look or behave like Lynch, one can't help but see him as a Lynch stand-in for these scenes, as he reacts to the studio's weird proclamations with bafflement and rage. No doubt the scene wherein Kesher takes a golf club to an exec's car was a miniature outlet for Lynch himself.

Betty

Standing in stark contrast to Lynch's cynical view of Hollywood, represented by Kesher, is Lynch's optimistic view of Hollywood, represented by Betty (Naomi Watts), a bright-eyed hopeful Canadian actress looking to make it big. Betty, as a character, is a throwback to a particular Hollywood archetype seen in multiple showbiz dramas of the 1930s. She is wide-eyed, innocent, and unsuspicious. And Betty — as she drifts into L.A. and away from reality — eventually finds herself becoming the main character in two well-worn Hollywood genres: The film noir, and the cautionary tale. In the former, Betty teams up with a beautiful and mysterious amnesiac (Laura Elena Haring) who Betty finds unexpectedly hiding in her borrowed apartment. They choose the name Rita (à la Hayworth) for her, and delve into the dark world of crime to suss out Rita's true identity. In the latter genre, Betty attends auditions for big Hollywood projects, and finds the world to be far more intense — and far more merciless — than she previously expected. Betty will eventually cross paths with the Kesher character.

While "Mulholland Drive" will eventually be about Betty's eventual disillusion and disintegration at the hands of Hollywood's illusions, Lynch acknowledges the power that Hollywood — and Los Angeles in general — holds on the American consciousness. Hollywood success stories are a modern American myth; the promise of fame, so much glorious folklore. The promise of Hollywood fame is perhaps a 20th century analogue for Horatio Alger's ultimately empty promise that hard work and decency will lead to prosperity and strength of character.

But, oh! The allure! The magazine covers! The wealth! The attention! The awards! Betty longs for it. And not for vapid or prurient reasons; she doesn't want to indulge in a life of vice and conspicuous consumption. Betty is lured by that most ineffable of all Hollywood qualities: the glamour. And that longing for glamour has a preternatural innocence. It's almost like Betty is not a real person ... she is someone else ... dreaming of another, more innocent version of herself ...

Silencio

There is a pivot point in "Mulholland Drive" that reveals what might be — to postulate — Lynch's thesis. Over the course of their investigations into Rita's identity, Betty and Rita find themselves falling in love. This comes as a bit of a surprise to both of them. When in bed together, Betty asks Rita if she's ever slept with a woman before, to which Rita logically replies that she doesn't remember. A classic Hollywood love story, mercifully queered.

Later that night, Rita and Betty drift, dreamlike, out into the midnight streets of L.A., and find the back entrance to a mysterious theater called Club Silencio (really The Palace Theater in Downtown Los Angeles). Seated in the balcony, Betty and Rita watch the show, rapt and terrified. The emcee on stage announces that everything they're about to hear has been tape recorded. A trumpet player emerges playing a trumpet, then drops his instrument as the music continues. A worn-out chanteuse (Rebekah Del Rio) takes the stage and sings "Llorando," a Spanish a cappella version of the Roy Orbison song "Crying." It's penetrating and heartbreaking. Betty begins convulsing and has to be calmed. The chanteuse then collapses on stage as her singing continues over the loudspeakers. The spell is broken. Stagehands help her off stage as "Llorando" continues to fill the room.

That's Los Angeles: Mysterious, glorious, beautiful, heartbreaking ... and all illusory. Even if we know it is an illusion — there is no orchestra — we persist in believing in it. A showbiz metaphor for Hindu Advaita Vedanta philosophies: The world phenomenal is maya, and the truth will mean untangling yourself from your worldly attachments.

Diane

Betty does free herself from her worldly attachments. Shortly after the Club Silencio scene, the film unlocks — literally! A characters turns a key in a mysterious blue metal cube found earlier in the film, and the camera swiftly zooms into it. A cowboy appears and tells someone (Betty?) that it's time to wake up.

The final act of "Mulholland Drive" is now about Diane (Watts), a parallel version of Betty, also played by Watts. This world is a darker, sadder place, full of familiar faces and locations, but now marred by alienation and depression. Diane is on the outs with her girlfriend Camilla (Harring), who is in the long process of leaving her for the Kesher character, abandoning Diane in an emotional abyss. Diane is in the process of discovering that she was perhaps the "secret girlfriend" of an insensitive, semi-closeted lover (although Harring later kisses Melissa George in the middle of a party, adding much salt into Diane's wounds).

The relationship between Diane and Betty is merely a matter of idle speculation, and discussions about their shifting identities, while making for a fun pseudo-intellectual klatch, will warrant no palpable conclusions. Is Diane the dark fantasy of Betty, who was "corrupted" by death and artifice in the city of Angels? Or is Betty the escapist fantasy of a wounded woman, hurt by love, hurt by the closet, and hurt by the lie of Hollywood glitz? Cannot both be true? What we do know is that Diane/Betty were both eventually led down a dark path by the promise of love and glamour, and both ended up disappearing in their separate ways.

This pivot of identities will feel familiar to fans of Lynch's 1997 film "Lost Highway," which featured Bill Pullman spontaneously transforming into Balthazar Getty. Looking forward, Lynch would also express a deep interest in the sublimation of human identity as it sinks into cinema with "Inland Empire," where Laura Dern plays an actress who makes the ultimate sacrifice to the audience by disappearing into the identities of others, i.e. acting. "Highway," "Drive," and "Empire" serve as a thematic trilogy of sorts, wherein Lynch explored the very concept of identity, the transmigration thereof, and how the cinema camera can reach deep into your heart and find where the emptiness may be hiding.

Or maybe not! At the end of this article, we should still acknowledge that spinning our wheels will still remain secondary to the films themselves. Better to go watch them instead.

"Mulholland Drive" is currently on the Criterion Channel.