The Classic Crime Novel That Inspired The Big Lebowski

The Coen Brothers' 1998 film "The Big Lebowski" has become a cult hit of the highest order, inspiring annual conventions in both Louisville, KY (Lebowski Fest) and England (The Dude Abides). It's odd that such a nonchalant feature film should move so many to such passion — surely the more appropriate response would be hole up with a White Russian (if you're over 21!) or an edible (if you're of age and they're legal in your area!) and try to get on the same lazy wavelength as The Dude.

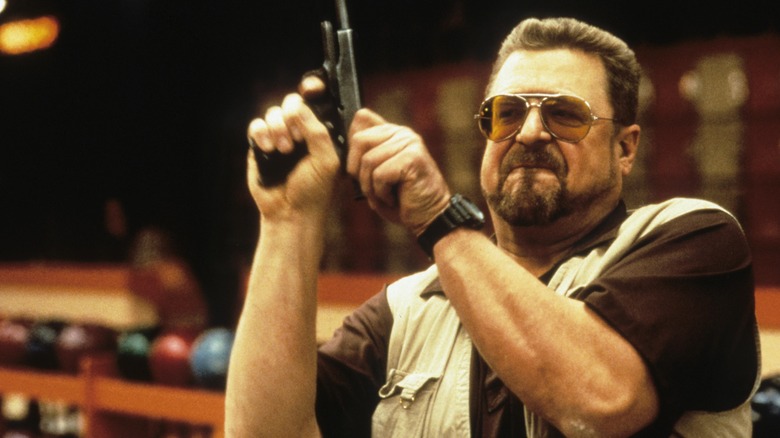

This part is well known: The Dude (a.k.a. Jeffrey Lebowski), played by Jeff Bridges in the film, was inspired by producer/activist Jeff Dowd. Dowd was one of The Seattle Seven, and produced several Hollywood films prior to "The Big Lebowski." The character of Walter, portrayed brilliantly by John Goodman, was inspired by director John Milius, who wrote several notable films — including "Magnum Force" and "Apocalypse Now" — and who directed "Big Wednesday," "Conan the Barbarian," and "Red Dawn." Milius was a warmonger and a gun nut, and many of Walter's ravings about Vietnam were at least partially lifted from Milius' rants.

In terms of story, however, "The Big Lebowski" took much of its inspiration from a source that matches the film's genre, but not its tone: Raymond Chandler's classic hard-boiled detective novel "The Big Sleep."

Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler is often credited for inventing, or at least popularizing, "hardboiled" detective fiction. A poet and a journalist, Chandler is best known today for his seminal crime novels "The Big Sleep" (1939), "Farewell, My Lovely" (1940), and "The Long Goodbye" (1953). Chandler typically set his stories in Los Angeles, creating a dark myth of the city as well as popularizing L.A. as a setting for crime novels. In his introduction to the 1950 short-story collection "Trouble is My Business," Chandler wrote that the difference between hardboiled detective novels and Agatha Christie-style murder mysteries is that the latter are more meticulous and devoted to clues, allowing readers to potentially solve the mystery before the denouement. Hardboiled novels are more immediately emotional, focusing more on the confusion and danger of the situation than the details of the crime. Indeed, the mysteries at the center of hardboiled novels were often difficult to penetrate in any kind of meaningful way, leaving readers awash in mystery. "The ideal mystery was one you would read if the end was missing," he wrote.

Chandler also offered one of the best pieces of writing advice I've ever encountered: If you're suffering from writer's block, and you don't know where to take your story next, simply have two men with guns burst into the room. The action will continue apace.

Chandler's novels have been adapted for film many times, famously in the 1946 version of "The Big Sleep" with Humphrey Bogart and a 19-year-old Lauren Bacall. The 1973 Robert Altman adaptation of "The Long Goodbye," meanwhile, has more in common with "The Big Lebowski": It transposes the action to the present, and makes the novel's central detective Philip Marlowe into a laid-back character who's befuddled as often as he's on top of the case. (This approach would be tried again in 2014 with Paul Thomas Anderson's film "Inherent Vice," based on the novel by Thomas Pynchon.)

Hardboild stoners

"The Big Lebowski" borrows only minor plot points from "The Big Sleep," and playfully mutates the sweaty, hard-boiled tone of the novel into, well, a stoner comedy. (In the film's opening scene, Sam Elliott's cowboy narrator muses that sometimes there's a man .... that ... and then loses his train of thought.) What "Lebowski" does take from Chandler is its setting, as well as the general sense that one is a little bit lost. Both genres are very much about being distracted and unable to focus on the mystery; in one, it's because you live in a morally empty world where heroes no longer exist and stopping crime and corruption will only be a temporary salve on the way to dusty death. In the other, it's because you've had some prime chronic.

"The Big Lebowski" was the Coen Brothers' third film based on works by a famed mystery author. Their debut, "Blood Simple," took its cues from James M. Cain ("Mildred Pierce," "Double Indemnity"), while their gangster film "Miller's Crossing" took its iconography from Dashiell Hammett ("The Maltese Falcon," "The Thin Man"). Those films, while each stylized in their own way, are more direct homages to their source material than "The Big Lebowski," which — like its protagonist — is comparatively loose.

"Lebowski" is about clues that never pan out, a murder that never happens, and a mystery that didn't really teach anyone anything. And yet, at the film's end, when The Dude is back to doing exactly what he was doing at the beginning of the film, there is a strange, meditative catharsis. There may be something to be said for abiding.