Breaking Down The Biblical Imagery Of The Batman

Much like Robert Pattinson's version of the Caped Crusader himself, "The Batman" isn't a movie that even attempts to hide its various influences. As Bruce Wayne mopes around Wayne Tower (on the rare occasion that he's actually there and not beating criminals to a pulp on the streets, that is) and listens to Nirvana like a total emo edgelord without an ounce of self-consciousness, director Matt Reeves adds to his already-impressive filmography with yet another thoughtful, ambitious blockbuster that reveals some fascinating sources of inspiration.

Much of the anticipation in the lead-up to release has been dominated by all the unmistakable parallels to movies like "Se7en" or "Zodiac" — not without good reason, of course. But focusing exclusively on those specific cinematic predecessors would do a disservice to everything that Reeves brings to the table in "The Batman." The filmmaker has never hesitated to infuse these sorts of pulpy stories with iconography lifted directly from classic literature and myth. Think of how he approached "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes" with no sense of irony or condescension, instead taking a page out of Shakespearean tragedy to depict the inevitable conflict between Caesar's advanced society of apes and a local settlement of surviving humans. "War for the Planet of the Apes," meanwhile, doubled down on the dour atmosphere of the previous film and took things in an even grander direction for the threequel. Biblical imagery, historical epics, and various war films of decades past all functioned as a roadmap to bringing Caesar's story to a fittingly operatic end.

"The Batman," as it turns out, works on multiple levels: 1) as yet another reinvention of a well-worn franchise, and 2) as a fascinating new entry from one of our best blockbuster filmmakers, bearing all the hallmarks and fingerprints of his previous efforts. Superhero movies going full Biblical on us is nothing new, especially in recent years, but Matt Reeves' particular approach to "The Batman" stands apart for its subtlety, nuance, and on-point thematic precision. Of all the aspects begging for discussion, it's worth diving into how this reboot uses Old Testament imagery to add to our understanding of a very familiar pop culture icon.

Major spoilers for "The Batman" follow.

Bruce Wayne, Batman, and ... baby Moses?

Probably one of the more divisive elements of "The Batman" may be rooted in the apparent lack of separation between the Batman persona and Bruce Wayne himself. Previous iterations of the superhero, from Michael Keaton to Christian Bale to Ben Affleck, have all taken full advantage of the different masks that the character is compelled to don across a broad range of situations. Robert Pattinson's version, meanwhile, immediately sticks out like a sore thumb (drive?) for his unapologetic disinterest in maintaining the brash, billionaire playboy façade. There are several justifiable reasons for this approach — like the fact that Bruce is depicted much younger in this film and hasn't needed to establish his public-facing image just yet — but I'd argue this goes hand-in-hand with the choice to position the hero as a Moses metaphor.

Thankfully, we need not be Biblical scholars to understand what Matt Reeves and co-writer Peter Craig are going for here. Anyone who's watched "The Prince of Egypt" or "The Ten Commandments" knows the broad strokes of the Israelite brought up in immeasurable wealth and security among the Egyptians. "The Batman" emphasizes Bruce's upbringing as an orphan time and again, which neatly parallels Moses' biological parents sending the infant away on the Nile river to avoid genocide on the orders of the callous pharaoh. (Of course, one major difference is that Moses gets to enjoy many years of peace as royalty among his adoptive family. Cynical Bruce, meanwhile, repays Andy Serkis' loyal and would-be father-figure Alfred over the years with the cruelest twist of the knife: "You're not my father.") Both Bruce Wayne and Moses share the same historical DNA, stemming just as much from the privilege inherent within their respective family dynasties as their eventual self-loathing at being a part of that power structure in the first place ... until each of them makes the fateful choice to take a much different path altogether.

Here, the creative decision to turn Pattinson's Bruce Wayne into a reclusive shut-in suddenly snaps into focus. Where Moses turns his back on the Egyptians and instead sides with the enslaved Israelites, Wayne turns to the cape and cowl to save the innocents of Gotham from rich crime lords. When the time comes for Batman to essentially become reborn in floodwaters and lead citizens to safety, well, consider that his parting of the Red Sea.

The ivory (Wayne) tower

The downright Biblical question of legacy and historical evils passed down from one generation to the next hang heavy over the events of "The Batman," with Paul Dano's terrifying Riddler pronouncing his sadistic judgment on everyone he deems worthy of it, from mayors to commissioners to district attorneys to Bruce Wayne himself. The delusional serial killer sees himself as a partner in crime with Batman, leading him on a bat-and-mouse chase and forcing him to uncover Gotham's sins right alongside himself. But none of those fond feelings (in a twisted sort of way, naturally) extend to Bruce Wayne, the last and greatest victim in the Riddler's schemes.

By day, Bruce must be prodded into going through the motions as one of Gotham's royalty, the very avatar of the rich and powerful whom the Riddler has branded the enemy of the people. Forcing himself to shed the comforting cocoon of his Batsuit and attend the former Mayor's (Rupert Penry-Jones) public funeral as he's expected to (even if only to keep an undercover eye out for a gloating Riddler), he runs into a cynical funeral attendee waxing poetic about influential people like the mayor deserving what he got. The damning moment lingers, both on-screen and in Bruce's id, adding to his already-intense guilt of, in the words of mayoral candidate Bella Reál (Jayme Lawson), not "doing more for this city." The Wayne-emblazoned cufflinks he borrows from Alfred for this event might as well be chains, weighing him down with the oppressive failings of his family legacy. By night, he's freed from these suffocating constraints and partners with Zoë Kravitz's Selina Kyle/Catwoman. Her presence keeps him grounded as a result of the various hardships she's had to overcome. In fact, she quickly deduces that Batman must've grown up rich without ever needing to know who lies behind the mask. Bruce's inherited sins aren't so easily buried, after all.

By the time Batman and the Riddler finally come face-to-face, the murderer efficiently lays out the blatantly disparate paths he and a young Bruce Wayne had to walk as fellow orphans. He bitterly remarks upon Bruce's ability to hole up in Wayne Tower, a way to look down on everyone else from an ivory tower — itself a phrase lifted straight from scripture. By exposing Thomas Wayne for what he was, the Riddler tears down Bruce's world around him.

Welcome to Gotham, the tenth circle of hell

It wouldn't be a proper "Batman" movie without dreary visuals and silhouette-tinged cinematography, which Matt Reeves and masterful director of photography Greig Fraser ("Dune," "Rogue One: A Star Wars Story," "Zero Dark Thirty") pull off with eye-popping flair. But more than merely securing prominent placement on One Perfect Shot for years to come, the creative team needed to find a way to communicate Reeves' hellish vision of Gotham and Bruce Wayne's callow recklessness into the visuals of the story, as well. The answer? Drenching the proceedings with vibrant reds and pitch-dark blacks. Pulling from established chiaroscuro techniques to achieve the unforgettable aesthetic, it's as if Bruce's tortured psyche had broken loose and set all of Gotham aflame.

It wouldn't be much of a stretch to posit that the rotting, morally bankrupt city stands in for the notoriously debauched Biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Traditionally, the legend acts as a parable of the mythological flood narrative, in which God destroys almost the entirety of unrepentant humanity in righteous anger. Reeves channels fire and brimstone throughout "The Batman," evoking the idea of waking visions of hell spilling over into the streets of Gotham. Consider when the souped-up Batmobile gives chase to the sinister Penguin (Colin Farrell) before ending in the instant-classic shot shown in all the trailers, or Wayne Tower itself coming under explosive attack by the Riddler.

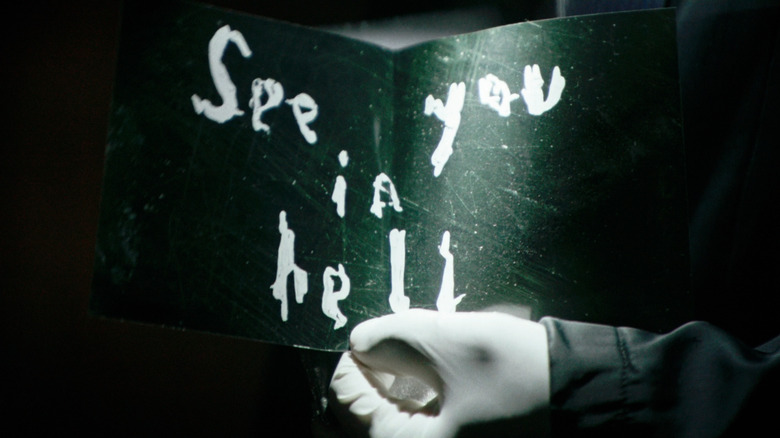

Both examples, combined with all the third-act flood imagery (the juxtaposition of rain with flames becomes a recurring motif throughout the movie), call to mind artwork like the 1822 Eugène Delacroix painting "The Barque of Dante," depicting a scene from "Dante's Inferno" where the poet Dante travels across the River Styx in hell as the City of the Dead burns behind them. I don't need to point out what Gotham City would represent in this analogy, do I? In any case, the Riddler turns all this subtext into actual text with the delivery of his last letter addressed to Batman and stating that he'll "See you in hell," which he pointedly calls back to once behind bars (er, very heavy-duty glass?) in Arkham Asylum.

Unlike past "Batman" movies, "The Batman" takes a mythical approach to the character. Biblical parallels might not be anyone's main takeaway from the film, but it simmers just beneath the surface, waiting to reveal itself like a festering lie.