FLCL's English Translation Was A Uniquely Tricky Process

I'll be honest, I don't typically listen to English anime dubs. That doesn't mean that dubs aren't important — They're the only accessible means by which blind folks who can't understand spoken Japanese can experience anime. They're also the format by which anime is broadcast on television, spreading the medium to new audiences. Seeing "Digimon Tamers" and "Fullmetal Alchemist" as they aired definitely shaped my tastes as a young person. But these days, I'm far more likely to seek out the subtitled versions. I'm a fast reader, and voice acting is a field whose nuances I've never taken the time to pick up. When given a choice between the source material and a transformative version that adds an additional interpretive layer through English voice acting, I would go for the source material every time. Even if that means avoiding popular dubs beloved by fans, like the ones for "Cowboy Bebop" and "Yu Yu Hakusho."

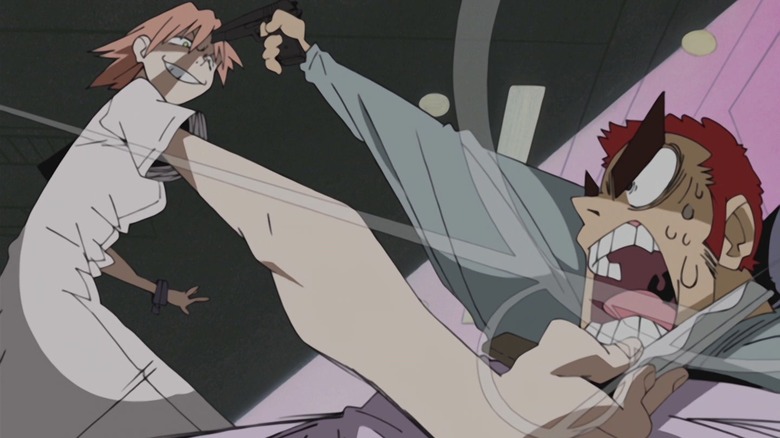

However, I have one exception: the anime classic "FLCL." It's my favorite series of all time, a blast of adolescent malaise, bizarre animation and rock and roll guitars, and it's as immediate and transient as lightning. I have watched "FLCL" more times than any other anime I can think of, and every time it has been the dub version. Not once in my life have I been tempted to resort to the subbed version. Whenever I hear series antagonist/femme fatale Haruko Haruhara shriek the word "lunchtime," that's English voice actor Kari Wahlgen blasting through my laptop speakers. What's most impressive about this feat is how poorly "FLCL" lends itself to a dub, at least in theory.

"FLCL" is loaded with double entendres, pop culture references and plenty of straight-up nonsense. The dub team at Synch-Point faced a stiff challenge in transforming the source into something comprehensible to English audiences while maintaining the spirit of the original. Their success wasn't just a landmark release for anime translation, but it's proof that, despite any personal reticence on my part, anime dubbing is as fascinating and complex a part of the medium's history as animation itself.

It takes an idiot to do cool things

Mark Handler, the ADR director and writer of the English dub of "FLCL," was as aware as anyone of the challenges faced by the project. In an interview with the late journalist and critic Zac Bertschy at Anime News Network, he discusses the show's "literary" nature and the challenge of bringing that quality to an English-speaking audience. He also says two things that, at first glance, appear to contradict each other. First he stresses the importance of faithfulness, saying that "our mission was to take what was there and bring it to an American audience as faithfully as we possibly could." You'd think from that statement that the team dubbing FLCL meant to keep as close to the source material as possible. But then Fisher proceeds to say, "if it's a double entendre, a play on words...if you do a direct translation, you've lost the juice." In other words, accuracy isn't enough. To do justice to the humor of the source material, sometimes you have to make something up.

The debate between accuracy and flow in translation continues to rage in English fan communities, even today. Anime fans insist that they want faithful, uncompromised versions of their favorite series. But the folks translating that anime know that adhering too closely to the source material results in stilted English that fails to convey the nuances of the original. Voice acting complicates the situation even further, presenting new tools to help deliver the story as well as unique challenges like lip flaps and timing.

At its best, the dubbing process produces iconic lines such as, "Hey, bitches and bros and nonbinary hoes!" from fan-favorite anime "Sk8 the Infinity". There's nothing like it in the Japanese version, but it fits the universe of the series perfectly. At its worst, the dubbing industry produces the infamous "Ghost Stories" dub, which not only spits in the face of its sedate but good-natured source material but encourages its fans to do the same.

But I don't like sour stuff

In the best existing resource I've found on the "FLCL" dub, "Why the FLCL Dub is So Important," video essayist Cartoon Cipher brings up two important decisions made in the dub's production that successfully unite accuracy and adaptation. The first was close coordination between Japanese and English crews from beginning to end. Not only did the creators of the series at Gainax and Production IG provide Fisher with extensive cultural notes for every cultural reference in the series. They also helped to provide equivalents for English-speaking audiences, to place them within the same nostalgic framework as the Japanese version. There's also the presence of Japanese staff like Production IG's Maki Terashima, who, according to Fisher, attended nearly every recording.

The second was casting with an ear for vocal essence, just like series director Kazuya Tsurumaki did for the Japanese voice track. Kari Wahlgren was hired to play Haruko despite her lack of dubbing experience because her delivery sounded exactly like that of Japanese voice actor Mayumi Shintani. Similarly, voice actor and producer Stephanie Sheh was picked for the role of Mamimi because a certain quality in her voice matched that of the original actor. Wahlgren and Sheh were led to replicate the inflection of key scenes from the original as closely as possible, even when the lines themselves were reworded for English audiences. As Cipher points out, this sometimes leads to decisions that make no sense in English, like Mamimi referring to series protagonist Naota as "Ta-kun." But the majority of the English dub not only captures the character of the original voice acting but even rivals it for enthusiasm.

Nothing can happen till you swing the bat

"Creative teams need to find a synergy with the series they're adapting," Cipher says. "That synergy...leads to dubs that capture the spirit of the original without being defined by it."

Cipher precisely nails the most important quality, not just of dubbing, but of translation as a whole. While I believe directors like Bong Joon-ho are correct in encouraging audiences to venture beyond the "1-inch tall barrier of subtitles" when they can, translation is transformative. Even with subtitles, your experience with the text will be subtly different from the original. A full-scale localization only increases that difference. Yet to defer too closely to the source without a reason is an act of cowardice. The best translators and localizers don't simply copy the original in a new language — they capture something essential, even if that essence cannot be put into words.

For those willing to go digging, the anime voice acting community is overflowing with the spirit Cipher describes. It's a world replete with bizarre niches, like "abridged series" that skewer popular anime out of love and affection. It has a continuous history, bridging the past and future of English-speaking fandom in ways that defy contemporaneous efforts to erase or rewrite that history. It has its own set of success stories, not just for "FLCL" alumni like Wahlgren and Sheh, but for relative outsiders like the abridged series producer Team Four Star. Even bad dubs earn their share of fan affection, like the infamous "Garzey's Wing." The source material was bad to begin with, but it's the English voice acting that elevates it to disasterpiece.

When I first saw "FLCL" I was blown away by its ferocious creativity. Each successive rewatch has solidified my feelings towards it, but slowly but surely shaved away its mystique. I was worried the show would become a solved problem for me, a nostalgia object capable of inspiring warm fuzzy feelings but no longer able to surprise or to shock. It's why I'm always happy to stumble across communities that tackle those works from a completely different angle. You can't ever re-experience a piece of art for the first time, but you can always find another way in.