The Daily Stream: Drive My Car Is A Mesmerizing Tribute To The Healing Power Of Art

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

The Movie: "Drive My Car"

Where You Can Stream It: HBO Max

The Pitch: Actor and theater director Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and his wife Oto (Reika Kirishima), a screenwriter, appear to be the perfect couple, albeit one with a strange post-coital ritual. After they have sex, Oto enters a trance-like state and recounts surreal, seedy stories to her husband, which he'll then repeat back to her in the morning for her screenplays. But Yusuke soon discovers that he's not the only one who has this ritual with his wife. Upon arriving home early after a business trip, he witnesses her tangled up with another man, and quietly leaves, shocked by what he's seen. But before he can confront her about her affair, Oto dies from a sudden brain hemorrhage.

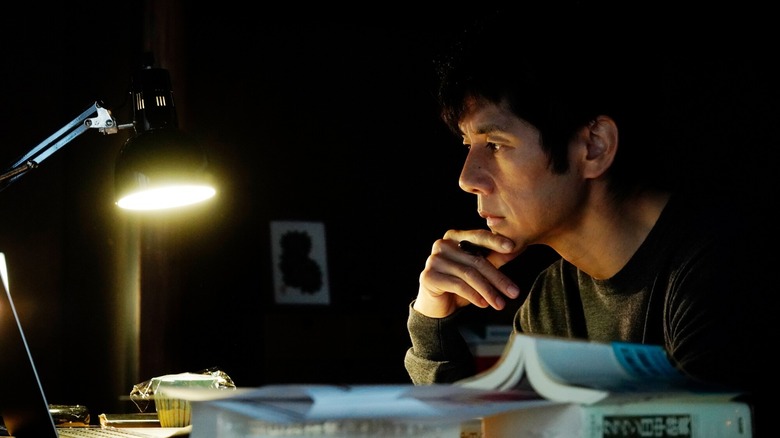

Cut to two years later, and Yusuke has taken on a job as director of a new staging of a play that he made famous, a multilingual production of Anton Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya." He's picked up a new, much more morbid, ritual: listening to the tapes that his wife made for him many years ago to help him memorize his dialogue, and reciting the lines opposite his dead wife's voice. But his ritual is interrupted when he's assigned a female chauffeur, Misaki (a quietly exceptional Tōko Miura), a stoic young woman dealing with her own demons. On top of that, while auditioning actors for the play, Yusuke encounters the very man with whom his wife was having an affair (a chilling Masaki Okada). But rather than being a recipe for disaster (or at least a little drama) as one would expect of these circumstances, "Drive My Car" takes Yusuke in an unexpected direction: on the path towards healing.

Why it's essential viewing

"Drive My Car" is remarkable for many reasons: It's a surprisingly humanist take on Haruki Murakami, whose short story of the same name serves as inspiration for the film; it's a rare depiction of a deep and transformative platonic relationship; and of course, it's three hours long — a runtime that flies by thanks to a laidback narrative and mesmerizing direction by Ryusuke Hamaguchi. But perhaps what's most remarkable is how "Drive My Car" so honestly and nakedly depicts how art can connect and heal even the most different of souls.

Art is how Yusuke and his wife Oto bonded, swapping surreal stories while tangled in the sheets together, bringing them closer together in a liminal space that feels both of this world and not. Art is how Yusuke is betrayed by Oto, who was apparently looking for creative inspiration elsewhere, and in liaisons with other men. Art is what brings Yusuke closer to Misaki, a fellow wounded soul who never really had an appreciation for theatre. Art is what brings together the strangers who would be cast in Yusuke's play — through a unique multilingual production of a Chekhov play in which they would all speak their own languages (Japanese, Korean, Chinese, sign language) without having to understand the others. But through art, they do understand each other, at least on some level.

All the world's a stage

There's a scene in the latter half of "Drive My Car" in which two of the actresses in Yusuke's play are rehearsing their scene together outdoors, Yusuke having decided to switch up the scenery after they had spent months doing robotic table reads indoors. Suddenly, something comes over the two of them. One of the other actors moves as if to do something, but Yusuke stops him — "they found it," he says. The two women act out the scene with increasing intensity, speaking in their separate languages, but that barrier that was between them before — of stiff rehearsal and non-understanding — has disappeared. It's almost as if they're not acting anymore, but simply speaking to each other, person to person. Chekhov's words are spilling out of their mouths, but something much deeper and more tender is playing out in their actions with each other. They hug and cry, emerging a little shaken, as if they were possessed by something other than themselves. But at the same time, it feels like the most honest and clear-eyed moment of the film until then.

Hamaguchi has always had a talent for charting characters and narrative through dialogue, which makes the conceit of "Drive My Car" such an intriguing fit for him. The characters have to overcome seemingly the most impossible obstacle — language — but in rehearsing a dead Russian playwright's story, they achieve a closeness that they might not have reached otherwise. Aren't we all rehearsing words and phrases put in our mouths? The "hello's," "how are you's," the "good mornings." Courtesy, especially in Japan, can be the biggest barrier between people, and we see how "Drive My Car" tears that down.

At the same time, sometimes those barriers exist for a reason, as we see in the case of the cryptic Kōji (Masaki Okada), the man with whom Yusuke's wife was having an affair. There's an impenetrable darkness to him that Yusuke soon discovers while working with him on the play, and it's one that cuts through some of the warmer stories of the people we encounter. And of course there's Misaki, who carries with her a bitter burden which Yusuke helps unload, while she in turn helps him decipher the mysteries of his dead wife. They all come together to form a rich tapestry of peoples' lives, some loving, some tender, some fragmented, some hopelessly lost. It's part of the beauty of "Drive My Car," that art can bring all these people together and mend some while exposing others — but connecting them all the same.