Dim The Lights: It's Time For The Return Of Overtures And Intermissions

(Welcome to The Soapbox, the space where we get loud, feisty, political, and opinionated about anything and everything.)

Matt Reeves' "The Batman" clocks in at just under three hours, you know. That's right, the new superhero offering from Warner Bros. sits at 175 minutes, which doesn't quite best the three-hour, two-minute runtime "Avengers: Endgame" but illustrates how epic Heroes' Journeys have become the norm for moviegoing audiences.

Of the longest movies of the 2010s, the majority of epics (fantasy or otherwise) have been comprised of auteurs and IPs: Martin Scorsese's "The Wolf of Wall Street" needs no cape to tell the story of Jordan Belfort (the filmmaker's "Silence" is also on the list of long yarns), but it does need three hours of audience time; "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey" and its follow-up "The Desolation of Smaug" are both over 2 hours and 41 minutes, while the alien robot saga of "Transformers" has a pair of two-plus hour movies on the list. Even at home, the Bingeclock enables those with the time to watch their desired TV series and movie franchises in bulk.

The data is in: the long movie here to stay. Why not bring back the old seventh-inning stretch for movie fans? The intermission was a relic of cinema, but it doesn't have to remain that way. It's time for the return of the overture and the intermission.

Room for one more?

On the roster detailing the longest movies of the past decade, the most interesting entries on the list come by way of vocal cinephile Quentin Tarantino, whose most recent films "Once Upon A Time in Hollywood," Revisionist Western "Django Unchained," and taut stage-play-on–the-big-screen "The Hateful Eight" all run up over two hours and 45 minutes of mayhem. The movies themselves are all fantastic; it's Tarantino's old-school film presentation that led to something beautiful.

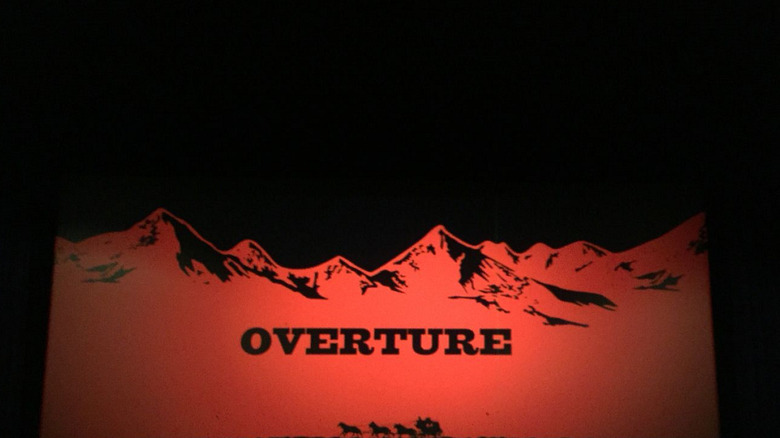

Upon the 2015 release of "The Hateful Eight," the "Jackie Brown" writer-director decided to usher moviegoing audiences back to a time when the movie was a capital-E Event. Through a limited engagement campaign, the ensemble Western opened on 100 screens across North America, and with none of that namby-pamby digital projection. No, "The Hateful Eight" would be projected in real deal Holyfield 70mm, a format that was good enough for the likes of "Lawrence of Arabia" and Christopher Nolan's 2017 war picture "Dunkirk." In this "roadshow release" of "The Hateful Eight," an overture and intermission would play. /Film's Jacob Hall had a chance to sit in on a screening, and he had this observation:

The Hateful Eight is a lot of things, but it is, above everything else, a crowd movie. Whether that crowd is laughing at its pitch-black comedy, cheering on its merciless cast of vicious characters, or cringing at the third act's brutal and bloody violence, this is a film that all but demands an audible reaction every few minutes or so. During the (hugely necessary and well-timed) intermission, you could feel the mixed reactions brewing in the air. For every filmgoer who was giddy to get back to their seat for the final stretch, there was someone else who was more wary about what lay in store. Although a 15-minute break in the middle of a three-hour movie allows for a fantastic physical break, the real pleasure came from having a chance to pause, think about what you've already seen, discuss your feelings with your neighbors, and mentally prepare for what comes next.

It seems that celluloid is still, as always, tantalizing and awe-inspiring as a format. The film was shot on 65mm, with classic Panavision lenses shooting the ridiculously wide aspect ratio of 2.76:1. The roadshow was a success, proving that the success of lensing used in classic films like Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" was evergreen and lending credence to the idea that film and digital can cohabitate in the same pop cultural space.

Let's all go to the lobby

The full roadshow experience is a pricey one, but including intermissions in tentpole films is not only doable, it's been done. In the mid-20th century, people had to be pulled away from their brand spankin' new television sets, and the onus was on studios to maintain A/V supremacy. So Paramount put out Cecil B. DeMille's "The Ten Commandments" the same year that 20th Century Fox churned out "The King and I" and United Artists released "Around the World in Eighty Days," all with overtures, intermissions with entr'acte, and/or exit compositions. Bring these back and it can help everyone — the studios, the storytellers they hire, the theaters they show the these pictures at, and the moviegoers who want both a movie and an experience without surcharges or needing to access a DVD special feature.

There is more than one way to watch a movie in the current landscape, and so studios these days are doing whatever they can to get butts in theater seats. Riding on the coattails of the 3D craze of the early 2010s (which faltered by 2018) and with theatrical attendance down before and during the pandemic, exhibitionists have started putting their eggs into the IMAX basket to keep profits rising after screenings of big-screen-friendly epics like "Dune" and "Spider-Man: No Way Home." But those fancy screenings have fancy surcharges attached to the price of admission. The onslaught of streaming and the advent of day-and-date releases have made staying home feel more convenient than ever.

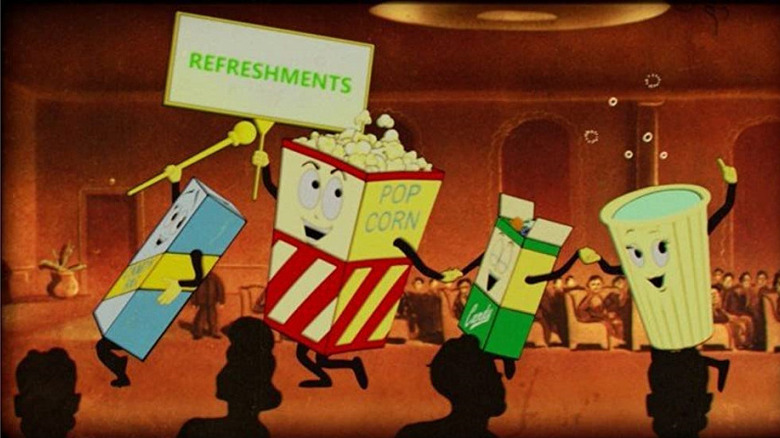

On top of providing projectionists a chance to switch reels, intermissions would give relief to patrons, provide a break between features, and maximize concessions sales, which is the bread and butter of most movie theaters. In 2020, when most theaters around the country had closed their doors, places like the El Capitan in Hollywood tried to stay afloat by selling their concessions curbside, promising "contactless pickup" for moviegoers. For a while, many independent theaters ran a catchy 1957 ad that encouraged patrons to buy snacks and tasty beverages. Filmack Studios' "Let's All Go to the Lobby," AKA "Technicolor Refreshment Trailer No. 1" played before the main show, and featured animated food items like popcorn and a soda urging the audience to grab something to eat in the theater lobby. It's iconic enough that it hasn't left the culture consciousness; throw pillows featuring the ad can be found and purchased on genre fandom websites like Horror Decor. Then and today, concessions (and the ads that support them) do the heavy lifting in supporting your local movie theater.

For your consideration

Perhaps the movie-as-event doesn't have to stay a pricey indulgence for the most avid movie-watchers; audiences have already shown that they're willing to sit through two-plus hour movies, so why not bring in musical breaks that showcase the very composers fans are paying to hear, and bring relief to both ticket buyers and the bottom line of movie theaters? As illustrated earlier, the movie already has the potential to be an "event," and enables storytelling flourishes that you can find in the stage setting, like the mid-feature cliffhanger. Imagine the Russo brothers breaking up the Avengers tale into five acts instead of the requisite three! Complaints of a padded second half would be nipped in the bud, and audiences are revitalized for the rest of the show following the break.

On a technical level, there's little need for the overture or the intermission; projection faculties have evolved along with arc lamps that eliminate the need for physical maintenance needed in decades past. Digital projection may be here to stay, but reviving the overture and the intermission music can help everyone — the studios, the storytellers they hire, the theaters that need direct support, and the moviegoers who want both a movie and an experience without surcharges or needing to access a DVD special feature.

Roger Ebert said it best, "No good film is too long, and no bad film is short enough." As audiences gleefully pour out of "The Batman" with three fewer hours left in their day, it seems that people are ready to attend something big, something they can't quite replicate from home, where you can always pause or skip the tunes. The theatrical experience can be reclaimed as an accessible event, and audiences are ready. Studios, particularly those with hefty IP collections like Warner Bros., should chew on it.