What We Talk About When We Talk About Spoilers

If you're a fan of gigantic, big-budget studio genre pictures, and you live on the internet, then you have likely already internalized the 12-step process of marketing anticipation:

Step 1: A studio announces a new film project surrounding a well-worn, and comfortingly familiar intellectual property of theirs, leading to enthusiasm from half of the intended audience, and skepticism from the other half.

Step 2: A few giddy news stories will be written, and pop culture pundits will mention the project on their podcasts.

Step 3: Two or three production stills will be released, sparking a firestorm of reaction videos and speculative articles about what is being done "correctly" and what is being done "incorrectly" in terms of extant canon.

Step 4: The teaser trailer will be released at a convention or on YouTube, forcing speculation and anticipation to grow. Fans and pundits will note how many views the video gets, and use that number as scientific evidence of how anticipated the movie is.

Step 5: A firestorm of speculative articles and podcasts hit the digital airwaves, and fans enter a fugue state wherein they begin scrounging for as much information about the film as possible in an attempt to "scoop" other fans, and define what the unseen film will be like.

Step 6: More marketing elements are released in drips over the course of the next few months, with each release inspiring a new round of speculation, articles, podcasts, Reddit posts. A consensus about the unreleased film has now been reached: This will be the Greatest Film of All Time. A general attitude and tone about the project calcifies.

The 12-step process

Step 7: Criticisms made in ill faith, which originated on the fringes, have begun to appear in more and more mainstream discussions. The unseen film is predicted by fringe-dwellers to have a vital flaw that will destroy its chances at the box office. These arguments are most frequently based in sexism and racism; the film will be "too woke," or a casting decision is "too political." "Too woke" and "too political" are code phrases used by racist people.

Step 8: Another preview is released. Information about what is included in international trailers becomes part of the discussion. Some fans have noticed that tie-in toys have character reveals that haven't been included in any of the marketing to date. Spoilers!

Step 9: Speculation about the unseen film's box office success become central to discussions about it. It will break X records. It will make upwards of Y dollars on Thursday previews alone. All pundits become financial prognosticators.

Step 10: Early reviews will hit. Fans will read them and then claim they don't read what critics have to say. It's around here that cries of "NO SPOILERS" begin appearing on social media. The reviews will, as the marketing process has dictated, contain juuuust too much information.

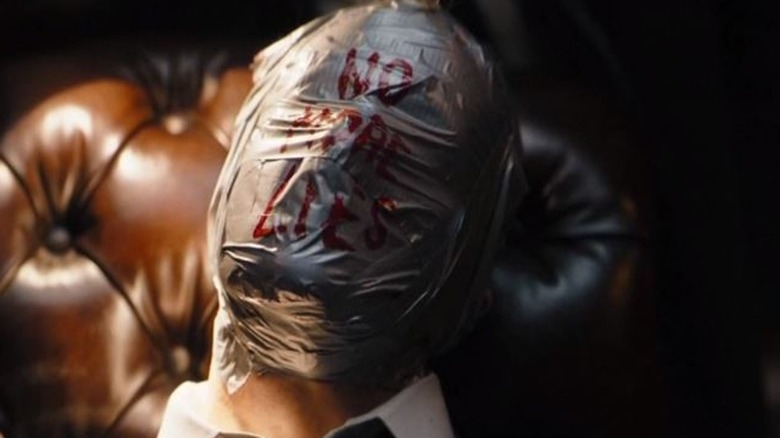

Step 11: A 48-to-96-hour information blackout period. No spoilers! No spoilers! No new trailers, no new information is permitted at this time. Anticipation is at its peak. Fans are frenzied.

Step 12: The film is released. Twitter gushes about the film for several days. It truly was everything the marketing had led us to believe it is. The information blackout continues through the opening weekend. All information about the film's plot and characters can be openly discussed the following Monday.

Repeat the process for the next blockbuster.

Do we really care about spoilers?

/Film's own B.J. Colangeno recently wrote eloquently on how spoilers don't matter as much as fans and pundits claim they do, and that knowing details about a film actually increase one's appreciation of the art in question. I agree with this point, as I have come to learn what "spoilers" actually are when it comes to the well-worn cycle of anticipation.

"Spoilers" are not necessarily the act of exposing vital story elements or ruining certain surprises that occur in the film — although they certainly are that; I recall Variety's Peter Debruge being lambasted for revealing Yoda's cameo in his review of "Star Wars: The Last Jedi." "Spoilers," more than anything, now refer to any "outside" information about a film that breaks from a very carefully constructed marketing and anticipation process mandated by the studios. The steady drip-drip-drip of officially sanctioned information must now come at a certain pace, as it's what fans have come to require in order to allow their excitement to crest into an outright furor.

A spoiler is anything that interrupts the marketing process. That involves plot reveals and details about surprises, yes, but it also involves basic descriptions of the film's plot, its tone, characters that may not have been included in any of the marketing materials, etc. This is why so many modern film reviews are peppered with "spoiler warnings": The basic act of describing a film's story — a requirement when reviewing a film — is not something that was previously revealed in marketing, and is considered to be too much information. It's not a spoiler to tactfully describe a film's plot, but, in the marketing-driven anticipation frenzy, it's an interruption, and will be described as such.

Information mining

The curious habit enacted by fans — frenzied with anticipation and feeding from the sparsely-refilled corporate marketing trough — is that, until that 48-to-96-hour blackout period, there doesn't seem to be any talk of spoilers. Indeed, many fans will go well out of their way to mine for as much information about an unseen film as possible. The cycle of speculation — based only on what marketing materials have ben released, mind you — will lead to deeper dives into the trenches of the internet. Pundits will overanalyze leaked snapshots taken from the set of a film in production, trying to suss out what a costume might mean, or what role an actor may be playing. Interviewers are often seen trying to "scoop" Kevin Feige or other filmmakers, hoping to get a "reveal." Most actors and filmmakers have come to steel themselves from such scrutiny, often falling back on teasing, winking stock answers to remain within the marketing flow.

It's actually kind of refreshing when Tom Holland lets major details about a film slip during an interview. The actor is humanly careless enough to stay outside of the studio mandated information cycle. However I may feel about him as an actor, I admire his brazen marketing cluelessness.

But there will eventually come an unofficially agreed-upon point in the marketing cycle when the above-mentioned information mining becomes gauche, and new information becomes anathema to the growth of excitement. To make it especially unfair to critics, reviews often arrive after this agreed-upon point.

The bigger problem

This hyperfocused anticipation cycle surrounding upcoming blockbusters my be described, however, as the mere natural order of things. Advertising is, after all, a mere conveyance of information about a product, mixed with exaggerations and style to connect a feeling to that product that consumers are then expected to get excited enough about to buy. That's all a movie preview is, after all. A little sample of a larger product. Roger Ebert once drew the simile that modern movie trailers are like the cheese cubes on toothpicks you eat at a grocery store. By eating a single bit, you know everything you can possibly know about that cheese, other than what it would be like to eat a great deal more of it. There's no real mystery; it's just a smaller version of the big thing you want.

But the anticipation cycle goes beyond merely being excited about an unseen film. The fealty to which many fans adhere to corporate marketing speaks to how the corporate marketing is the only source of information to be trusted. One can only experience excitement as it follows the dictates and caprices of a major company's marketing department. And fans are perfectly willing to lap up what is being dripped down to them. We live in a world where the business word "franchise" is used to describe a series of films without a hint of awareness or irony. Casual Twitter users comment relentlessly on what does and does not make for good marketing. People celebrate when they see a good marketing gimmick.

It seems the larger — and, to my eye, more problematic — element of the anticipation process is that fans, after having pledged fealty to the advertising blitz of the choice, are now more in awe of the way marketing is constructed than anything to do with the film itself. At some point, actually seeing the film almost feels like a tertiary formality.

My controversial take on all this: The best time to get excited about a movie is after you've seen it.