Year Of The Vampire: Ganja & Hess Is About So Much More Than Bloodlust

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

One of the best vampire films I have ever seen actually never uses the term "vampire" at all. Very early in Bill Gunn's unsung masterpiece "Ganja & Hess," we learn that Dr. Hess Green is addicted to blood. It's hard to tell whether this statement, delivered casually by Hess's chauffeur, is a literal fact or one that's yet to come to pass.

The bloodsuckers in "Ganja & Hess" are unlike any audiences in 1973 would have seen before. They had no fangs, they were impervious to sunlight, and could only turn a human by stabbing them with a ceremonial African dagger. Not only were they Black, but also affluent and refined, which seemed to confuse critics even more than the film's non-linear narrative. So many of Gunn's choices here are hard to analyze, but one has to wonder if they were meant to be analyzed at all.

"Ganja & Hess" was, in a lot of ways, Gunn's response to the Hollywood system that had chewed him up and spit him out in the '60s. The multihyphenate started off in the New York theater scene, writing and acting in plays before trying his luck out west. He even wrote a handful of successful movies — but he still chafed under the limits for Black stories at the time. The '70s might have seen the rise of the blaxploitation movement, but in the late '60s, the films that degraded the Black experience were the ones that made bank. Gunn was only approached to make "Ganja & Hess" in an effort to recreate the success of "Blacula," and though he'd certainly make a film about Black characters and their bloodlust, it wasn't anything like the film his backers were hoping for.

What It Brought To The Genre

"Ganja & Hess" was inarguably ahead of its time — and in some ways, even today, it still is. Gunn's hypnotic exploration of sexuality, colonialism, religion and addiction told through the lives of two unapologetic Black characters isn't all that common even now, although it's become increasingly popular in horror. "Ganja & Hess" deliberately flouts the western perspective. That the film's particular brand of vampirism originates not in Transylvania, but from an African civilization, shows how concerned Gunn is with shifting the narrative.

The film's credits play out over close-ups of marble sculptures, twisted white limbs and faces in anguish — but that's about as close to whiteness as "Ganja & Hess" gets. Gunn immediately pivots to a scene in a chapel, and introduces us to a Black preacher, Luther (played by Nina Simone's brother, Sam Waymon) who also moonlights as Hess's chauffeur.

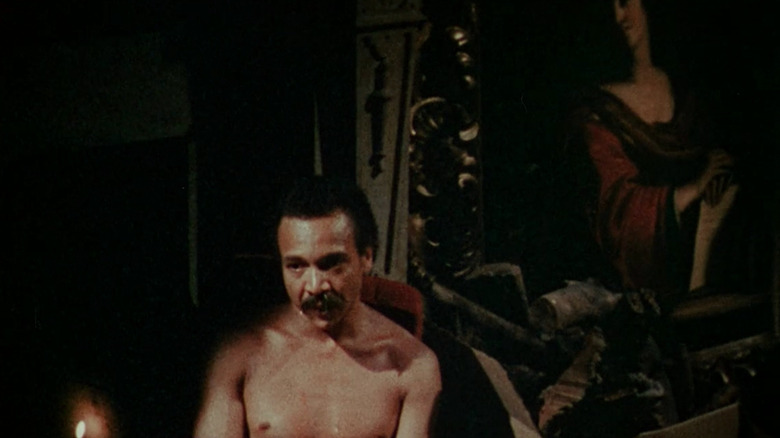

By contrast, Hess (Duane Jones of "Night of the Living Dead") is not religious at all. He's dedicated only to studying the Myrthians, that aforementioned African tribe, and the mysterious disease that wiped them out. The whole deal with the Myrthians is definitely a metaphor for colonialism: they were cursed with a craving for human blood, a curse that only the shadow of a crucifix could deliver them from. Ironically, Christianity wouldn't exist for centuries, which doomed the Myrthians to their bloodlust and eventual extinction.

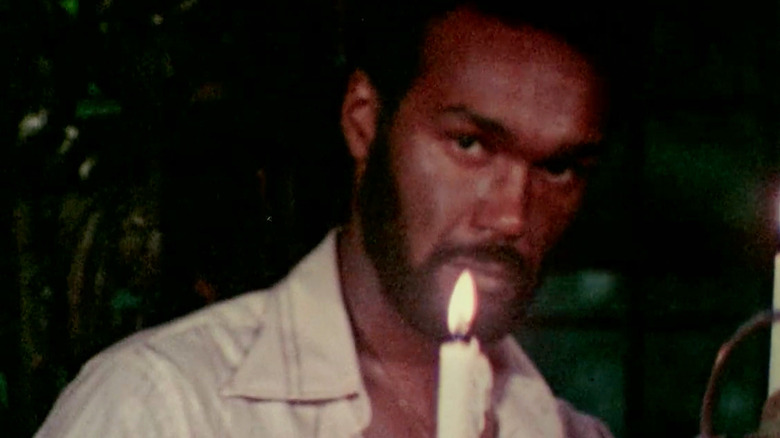

Despite his obsession with African culture, Hess is refined and distant in a way that likens him more to a figure like Dracula. He's able to send his son to boarding school and converse with him in French. He can afford lavish parties on his estate. But at the end of the day, he is still a Black man — the only one in his neighborhood. When his new research assistant (played by Gunn himself) attempts suicide at his house, he's more concerned with the "embarrassing" questions the police will ask him than the fate of his guest. He's able to talk Meda down at first, but soon after Meda attacks him with a Myrthian dagger and — according to the film's initial title cards — stabs him three times: once for the Father, again for the Son, and finally for the Holy Ghost.

Meda then sits down to write an open letter to Black youth; it also serves as his suicide note. He dies just as Hess is resurrected. His blood becomes Hess's first meal.

Enter Ganja

Hess is able to live, for a time, as one of the undead. He steals from blood banks and drinks neon-red blood from fancy crystalware. When that tactic fails, he preys on sex workers in the seedy parts of town, and feeds on people he's sure that no one will miss. Like in so many vampire movies, our protagonist fights to keep one foot in the human world — but it's taken a step further by conflating his curse with his African heritage. Whenever he feels the urge to feed, a pulsating drone rises in the score, as do the sound of drums and chanting. The connection is impossible to sever, but he works to suppress it as best he can.

His new system is disrupted when Meda's wife Ganja (Marlene Clarke) comes looking for her late husband. Their affair seems almost inevitable: Ganja is arresting, gorgeous, and uncompromising. When Hess asks her what she wants most in the world, she tells him money. She has a habit of interrogating him with impolite (even embarrassing) questions. "They're the only ones worth asking," she tells him slyly. Ganja is a woman that both challenges and intrigues Hess. Even with the secret of Meda's death festering between them, they still fall in love — or as close to conventional love as either can get.

They're not exactly a perfect match: Ganja, like Gunn himself, is almost antagonistic in her desire to be free. She sneers at any sort of adherence to the norm, while Hess tries everything he can — even, eventually, religion — to reclaim his humanity. Ganja is more afraid of living a life of obscurity than she is of becoming a vampire. She embraces the lifestyle without looking back; her lust for blood and for flesh heightens Hess's own. Her desires may seem erotic and materialistic on paper, but it's all in the pursuit of freedom — freedom to exist without shame, something that Black characters (much less Black women) are rarely able to attain.

"Ganja & Hess" is not so much a vampire film as it is a film that uses vampirism to unpack its themes. Obviously Gunn wasn't the first — and certainly wasn't the last — to contextualize a personal struggle within the framework of a horror film, but there's something about his efforts that feel intensely catered to his experience, and by extension the experience of any Black creative who feels stifled by the white gaze.

The Arthouse Double Standard

Unfortunately, the white gaze still influences so much of what constitutes a "good" film. For all Gunn's efforts, "Ganja & Hess" fared terribly — not just at the box office, but with critics as well. Overseas, it was the only American film to screen during International Critics Week at the Cannes Film Festival, but that carried little weight in the U.S. itself. The film was slammed by The New York Times; critic A.H. Weiler disparaged the film's "black-oriented" and "confusingly vague mélange of symbolism, violence and sex." Gunn hit back with a scathing response, which the Times also published a month later: "There are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with black creativity."

Gunn still found his creativity suppressed in other ways. His backers at Kelly-Jordan Enterprises pulled the film after just three days in theaters. Desperate to recoup their losses, they sold the rights to Heritage Enterprises, who re-edited "Ganja & Hess" into something more palatable, and even changed the name from its original title to "Blood Couple." The only reason Gunn's vision has prevailed today is because the director made two copies of the film and donated the unspoiled version to the Museum of Modern Art, who spearheaded a restoration years later.

Even now, there are those who claim not to "get" the film, which is a bit of a frustrating and telling response to a film that was almost destroyed by people who felt similarly. It's easy to dismiss a film when the experiences within it feel so disparate from your own. But people have suspended disbelief for less.

"If I were white, I would probably be called 'fresh and different,'" Gunn mused in his letter published in the Times. "If I were European, 'Ganja & Hess' might be 'that little film you must see.'" The reception of his film compared to similar films of the decade — "Suspiria" and "Repulsion" specifically — is a painful reminder of this sentiment. It's still difficult for Black filmmakers to express themselves without judgment or confusion, to really be free to make creative choices.

Understanding "Ganja & Hess" is easier with context, and only possible through empathy. It doesn't quite fit into the box of a vampire film, but that's because it's so much more: Gunn's last-ditch effort to tell a story on his terms (he would direct only one other film before his death), a stinging critique on assimilation, a fever dream ... However imperfect, it's a fearless effort from a director who refused to play by any rules but his own, and it opened the door for filmmakers like Spike Lee and Jordan Peele to express themselves without fear as well.