The French Connection's Famous Chase Scene Was Filmed In An Extremely Reckless Way

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"The French Connection" is renowned for having one of the greatest car chases in film history, but director William Friedkin used highly unorthodox and even downright dangerous methods to capture it. Many stories have circulated about Friedkin slapping priests and ambushing actors with projectile vomit on the set of his 1973 horror film, "The Exorcist," but before that came his guerrilla-style 1971 police thriller, "The French Connection," starring Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider.

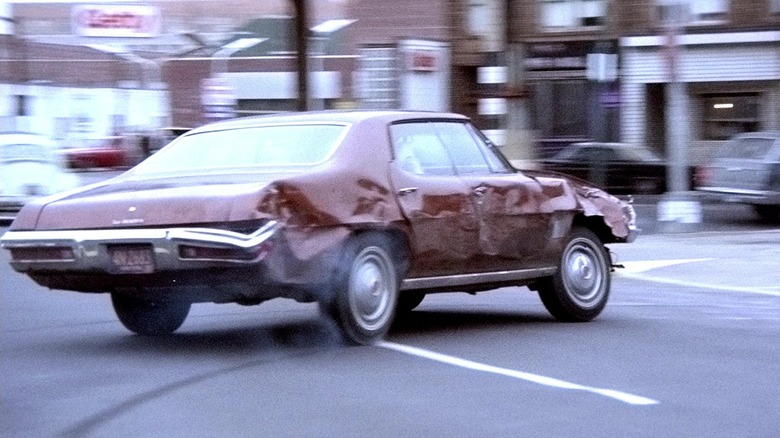

Friedkin's experience on "The French Connection" perhaps even emboldened him to go further and abandon the proverbial fear of God while filming "The Exorcist" — all in the name of art — since by then, he had already survived that death-defying car chase, filmed mostly in one take and in real traffic, on streets not blocked off in New York. Honestly, it was an accident waiting to happen. According to Hagerty, Friedkin spent weeks goading "French Connection" driver Bill Hickman before Hickman got behind the wheel of the stunt Pontiac LeMan, with Friedkin working the camera over his shoulder. The incensed driver slammed on the accelerator, running stoplights and driving up to 90 mph for over 25 blocks.

Like Hackman's reckless cop character, Popeye Doyle, Friedkin was obsessed with getting what he wanted — in this case, a pseudo-realistic, documentary-like chase.

The French Connection car chase was incredibly dangerous to film

To shoot the chase sequence, they had a siren mounted on the car, and William Friedkin had worked the chase out beforehand with his actors (including the woman pushing a baby carriage, who Popeye almost hits). Friedkin was able to shoot some scenes on the overhead train Popeye was chasing by bribing an official with $40,000 and a get-out-of-town ticket to Jamaica. What he didn't have was a permit to shoot on the street, let alone endanger the lives of real Brooklyn motorists.

Friedkin did have crew members and off-duty cops working to help him contain the situation, so it wasn't like he just stuck a runaway car in traffic with no buffers. However, there was no official traffic control, and during a sequence where the late great Gene Hackman was actually driving, there was an unscripted collision with another stunt vehicle. That moment made it into the film! (Believe it or not, Hackman was really behind the wheel more than you might expect, with Friedkin telling the Directors Guild of America, "I should point out that he drove considerably more than half of the shots that are used in the final cutting sequence."

Apparently, Friedkin, in his guerrilla filmmaking zeal, recognized how hard he was gambling, which is why he was working the camera, since, as a bachelor, he could afford to die young, unlike some of the other family men in his crew. Friedkin identified the theme of "The French Connection" as "the thin line between policeman and criminal." Behind-the-scenes stories like this also go to illustrate what a crazy-thin line there is between artist and criminal sometimes — including but not limited to, times when creative risk-taking spills over into on-set or on-location safety hazards.

Friedkin admitted he put lives at risk during the French Connection chase scene

William Friedkin got lucky since no one was seriously injured, but in a post-"Rust" industry, it feels like he or any filmmaker would not be able to get away with some of the things he did on the set of his movies in the 1970s. In 2021, he implied the car chase put people at risk when "The French Connection" was celebrating its 50th anniversary, saying:

"I was like Captain Ahab pursuing the whale. [I had] a supreme confidence, a kind of sleepwalker's assurance. As successful as the film was, I wouldn't do that now. I had put people's lives in danger."

"Ahab" is a reference to the Herman Melville novel, "Moby-Dick," which ends with a vortex dragging an obsessed whale hunter down into the sea in a hearse of America-grown wood: his ship. That feels like an apt metaphor for the '70s American New Wave and all the filmmakers, like Friedkin, whose careers somewhat crashed and burned after the cinematic heights of that era.

"The French Connection" remains a classic, and watching the above chase with knowledge of how it was filmed does raise the tension of it, but would it be any less great had it been filmed under less perilous conditions? Did the real-life danger somehow contribute to the film's visceral power, or could it have been made to look just as authentic with some movie magic? These are questions that drive (chase pun intended) film discussion in the 21st century.