Year Of The Vampire: The Lusty Legacy Of The Lost Boys

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

Soon after my siblings and I reached adolescence, our mother made sure to give us a good old-fashioned cinematic rundown of the films that helped shape her own understanding of the world when she was around our age. Luckily for us, mom always had a penchant for the morbidly hilarious. MPAA ratings never factored into what she was willing to show us, meaning Sunday afternoons in the Keogan household would regularly consist of matinees of "An American Werewolf in London," "Jaws" (which is only rated PG!) and, most importantly, "The Lost Boys." The overt 70s/80s overtones of these films helped minimize their horrifying impact (though it was admittedly hard to swim in the local Jersey watering hole after watching "Jaws," despite all of my wisecracks concerning how "fake" the shark looked), and we were genuinely delighted to have a window into our mother's previously unknown filmic tastes — even if the more salacious elements of these movies were a bit awkward to process during early pubescence in her company.

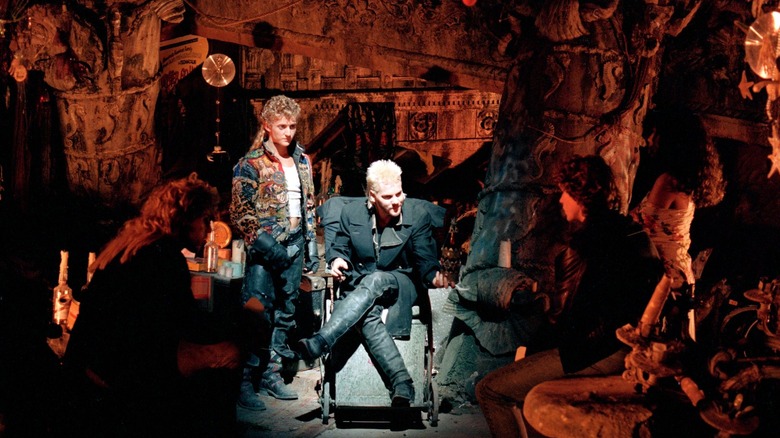

Why "The Lost Boys" in particular struck such a cord — both for us and our mother — definitely has a lot to do with how emblematic it feels of that particular era of pop culture. Though it was released during Ronald Reagan's second term, the film is totally in touch with the acts of youthful rebellion that existed on the ostensible margins of the reactionary climate of the 80s. This probably has a lot to do with director Joel Schumacher's own identity as a gay man during the AIDs epidemic, an anxiety that imbues the film with a heavy sense of fraught, fractured homoeroticism between mortal-turned-vampire Michael (Jason Patric) and blood-sucking coven leader David (Kiefer Southerland). Additionally embroiled in the thrilling danger and inherent sex appeal of living outside of society's conventions, "The Lost Boys" solidified the notion that our mom was (and still is) a deeply cool person with taste to boot — making these movie marathons all the more special as bonding exercises while also serving as benchmarks for understanding a bygone era (at least for a few 11 to 13-year-olds during the late aughts).

What It Brought to the Genre

If we're getting into the nitty-gritty of "The Lost Boys" plot points, what makes the film such a unique foray into vampiric cinema is its sunny California setting. Traditionally, the settings for these stories have provenance in dark, dreary corners of the world — Transylvania, London, Germany — as these locations provide ample cover for vampires from the sun's smoldering rays. Yet the fictitious city of Santa Carla (standing in for Santa Cruz) which hosts "The Lost Boys" inverts the classic vampire story on two fronts: it gives credence to the idea that vampires can infest any given area despite its climate, while also asserting that these vampires have to compensate for a lot considering their daytime disadvantage. In fact, there's almost an anti-drab air of liveliness to the city of Santa Carla — the sunny beachside feel which permeates the day gives way to a light-soaked metropolis by night, dominated by the luminescence of the boardwalk which becomes inundated with young people during the evening hours.

However, the overwhelming influx of pedestrians to this area doesn't translate to a safe congregation in numbers. These vampires flaunt their metaphysical powers, ripping roofs off of cars while couples canoodle and picking off security guards like lambs awaiting the slaughter. The sheer power this translates to only heightens the tension between Michael and David, who play a game of cat and mouse that is additionally bolstered by their rival desire for empathetic vampiress Star (Jami Gertz). This love triangle soon turns treacherous, with David's younger brother Sam (the late, great Corey Haim) and mother Lucy (Diane Wiest) becoming targets for the vampiric gang's brutality. Fortunately for Sam, teenage comic book purveying brothers Edgar (Corey Feldman) and Alan (Jamison Newlander) Frog freelance as experienced vampire hunters — a necessity for survival when living in Santa Carla. Not so fortunately for Lucy, her new beau (and boss at the local video store) Max (Edward Herrmann) is actually the de-facto leader of the coven, hiding his affiliation and allowing David to pose as overlord.

By obscuring the role of an exsanguinating elder, "The Lost Boys" also cements itself as a vampire film explicitly centered on the seedy, youthful underbelly of vampirism, a trend that would continue with the release of Kathryn Bigelow's Oklahoma-set "Near Dark" three months later.

The Spoils of Eternal Youth

The film's title in itself references a static state of adolescence, referring to the un-aging clan of boys from "Peter Pan" whose eternal youth has stunted their maturity, but dually grants them with an otherworldly power. Similarly, the band of vamps in "The Lost Boys" operate out of a malicious brand of masculinity generally reserved for boorish teenage boys, exemplified by their proclivity for petty vandalism alongside their unquenchable thirst for blood. Yet their constant evading of capture (or, perhaps more aptly, staking) signifies not only the supernatural origins of their abilities, but the power and privilege that men are trained to exercise from an early age. It's no coincidence that both David and Max are possessive of the women in their lives, nor that the violence they inflict upon a comparatively vulnerable community goes without reproach.

Perhaps this is also why the dynamic between Michael and David is so embittered yet twinged with erotic sentiment—in their inability to comprehend and embrace their attraction for one another, they are forced to detest each other in order to fit into the mold of patriarchal manhood which they've been all but indoctrinated into since birth. Particularly when the jealousy seeps in after Michael has sex with Star — who until that point had been "David's woman" — the two boys are locked into a death match due to their incapability of expressing mutual desire. For a group of guys who seem to wear nothing but leather ensembles and dangly silver earrings, one would assume that an assertion of queerness would come naturally, but alas.

The antics of Sam and the Frog Brothers are also a useful foil to the more sexually charged activities of Michael and the coven, as their singular focus on comic books and vampire hunting serve as a window into the pop culture preferences of youths during the late '80s. Though the unyielding grip of hormonal changes are just on the horizon, all these boys care about are rare Superman comics and staving off night stalkers. This gives "The Lost Boys" mass appeal among teenagers of all ages, while also serving as a veritable time capsule of what the youth was engaging with and responding to circa 1987.

A Pop Culture Sensation

Okay, I'll say it: "The Lost Boys" is probably not the greatest vampire movie of all time. But what it lacks in gore and ingenuity it more than makes up for in cultural longevity. It influenced the first cinematic chapter of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" (where teenspeak and vampirism also converge) and inspired arguably the funniest bit in the undead mockumentary movie "What We Do in the Shadows." Hell, even the oiled-up saxophone player Tim Capello has garnered infamy from his 20 seconds of screen time in the film — a veritable sex symbol who has become popular GIF fodder 35 years on.

"The Lost Boys" is also incredible for the glimpse it provides into the decade's star power, particularly when it comes to the then-duo of The Two Coreys (both of whom have experienced the bleak injustices Hollywood still perpetuates against child actors), Sutherland's stint as a teen heartthrob, the versatility of two-time Academy Award winner Diane Wiest, and even an early look at a glammed-up Alex Winter a few years before he'd rise to prominence for "Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure." However, the young people don't necessarily have the last laugh in "The Lost Boys." Despite the family's success in defeating Max, David, and their vampire lackeys, it's grandpa (Barnard Hughes) who utters the unforgettable final line of dialogue in the film. After impaling the vampiric ringleader with a stake attached to his truck, he calmly declares to his blood-drenched daughter and grandsons, "One thing about living in Santa Carla I never could stomach: all the damn vampires."

So next time you're having dinner with your mom, dad, aunt, uncle or other tangential relative who came of age during the '80s, ask them about "The Lost Boys." Chances are you'll be able to grade them on a scale from "bummer" to "bats***" based on their reaction. The critics may not have loved this wing-flapping flick when it originally hit theaters during the sweltering summer of '87 — but then again, legacy critics tend to not have their fingers on the pulse of what constitutes "cool" among young people. But hey, we'll just have to wait and see what there is to say about the imminent reboot of "The Lost Boys" — maybe this time I'll be the stuffy adult who just doesn't "get it."