The 7 Most Influential Movie Moments Of Douglas Trumbull's Career

Douglas Trumbull passed away on February 7, 2022, leaving behind a legacy that may never be matched. Having a technical mind from an early age (there are stories of a young Douglas building his very own crystal-set radio), as well an abiding interest in spaceflight and astral engineering projects — not to mention a love of alien invasion films — Trumbull was ideally suited to work on some of the most impressive science fiction films of all time. Trumbull's career began in the 1960s, exploded with his unmatched work on Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey," and lasted all the way until 2018 with his work on "The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot."

Trumbull was one of those technicians and filmmakers who managed to revolutionize the industry several times over during his career, constantly setting the bar higher and higher when it came to special effects. Here is a brief rundown of several times Trumbull pushed cinema to another level.

Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite

In 1964, Douglas Trumbull, a mere 22 years old, worked on a film for the New York World's Fair called "To the Moon and Beyond" which employed a new type of photographic technique dubbed The New CINERAMA – 360 Process. This was a process that involved shooting on 70mm film at 18 frames per second with a fish-eye lens. This technique allowed the film to be projected on a dome-shaped screen, creating a planetarium effect. "To the Moon and Beyond" caught the eye of director Stanley Kubrick, who was in production on "2001: A Space Odyssey" at the time, and he hired the team behind "Moon" — Graphic Films — to add scientific authenticity to "2001." The team at Graphic Films started corresponding with Kubrick, sharing maps and star charts, and eventually storyboarding entire space travel sequences. Trumbull was one of the background artists at Graphic Films, and was eventually hired independently to work on the background computer screens seen on the starships.

Once he was working on those screens, however, Kubrick continued to expand his role during the film's multiple-year production. Trumbull was eventually hired as a special effects supervisor who would work on the mind-bending Stargate sequence for the film. Notably, Trumbull employed a process called slit-scan photography in said sequence, which involved a placing slitted aperture plate in-between the camera lens and the photography subject, allowing for a "warping" visual effect. Trumbull did not invent slit-scan photography — that credit belongs to animator John Whitney — but he expanded the process with an enormous cinematic experience in mind, inventing one of the most mind-blowing experiences in all cinema.

The Andromeda Strain

Trumbull quickly developed a reputation for scientific accuracy, and his career took off (although Trumbull would admit in interviews that the experience of working with Kubrick was less than pleasant, pressured as he was into constant perfection). Trumbull soon started his own production company, and (under)bid to do the special effects on a 1971 science fiction film called "The Andromeda Strain," directed by Robert Wise and based on a hit novel by Michael Crichton. "The Andromeda Strain" is about a viral outbreak in New Mexico following a nearby flying saucer crash. Taking a "Star Trek"-like procedural approach, the film follows a very technical process — which all feels very authentic, and has been cited by specialists as being one of the only films to accurately represent this — of identifying, and then protecting a team of specialists from, an alien virus. Trumbull worked on the visuals of the virus itself.

While the process looks like CGI, Trumbull employed many similar photographic effects that he used in "2001," creating an eerie green blob that looks like an actual virus does in our heads. Trumbull made numerous short films of virus imagery which would be composited into the electron microscope sequences in the finished film. Although Trumbull has said that he likely could have asked for more money on "The Andromeda Strain" — Trumbull cites his naïveté for underbidding — the director was impressed, and the film was an enormous hit.

Silent Running

The success of "The Andromeda Strain" led to Trumbull's next triumph, this time as a director. The 1972 film "Silent Running" is a stirring environmentalist parable about a botanist (Bruce Dern) who cares warmly for a spacebound greenhouse-like spacecraft that contains the plants that can no longer survive on a near-ruined Earth. When the ship is ordered to be destroyed, Dern has to disobey orders and sabotage his fellow crewmates' efforts in order to save his beloved arboretum. "Silent Running" is a pointed and effective thriller about the environment, and Trumbull — ever seeking realism in space — shot the heck out of it (with cinematographer Charles S. Wheeler).

The ships in "Silent Running" are mostly nearby Saturn — the supermodel of the solar system — which was a realization left over from "2001." The story goes that Kubrick wanted the action in "2001" to be set near Saturn, but the planet's rings proved too difficult to realize, so the filmmakers decided on Jupiter as an alternative. In "Silent Running," Trumbull was able to bring Saturn back onto the screen, depicting its rings in all their glory.

The ships were all elaborate models, and Trumbull has said that the film's geodesic greenhouse domes in which Dern spent most of his time were modeled off of Missouri Botanical Gardens, which are housed in their trademark Climatron domes.

Response to "Silent Running" was mixed, as some critics felt the film was too melodramatic, but few lambasted its amazing images and attempts at a scientifically convincing visual palate. Although Carl Sagan did have time to be a stick-in-the-mud pointing out that plants in space-bound domes wouldn't get enough sunlight.

Showscan

Trumbull worked on the special effects for Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" in 1977 (he wasn't available to work on "Star Wars" that same year), which gave him ideas on developing a new process called Showscan. Showscan was a 70mm photographic process that was intended to increase the visual fidelity of film exponentially. The idea was to shoot 70mm film at 60 frames per second, allowing for a great fluidity of image, but with the glorious visual information permitted by the 70mm format. For some modern context, a digital 4K image still contains less visual resolution than 70mm film does; 70mm film is closer to the digital equivalent of 8K.

Additionally, the traditional speed of film remains 24 fps, despite what Peter Jackson attempted to do with his Hobbit movies (or what Ang Lee has been trying to do with several of his), while some TV shows broadcast at 30 fps. "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey" was released in some theaters with a 48 fps, and Ang Lee has gone as high as 120. In the digital age, high frame rates have been lambasted as looking too smooth or resembling television too much, and the world has not yet adopted it. This, sadly, was also true of Trumbull's efforts to revolutionize frame rates with Showscan, as no commercial feature films were made with the process. Only thrill rides, documentary shorts, and industrial films have used it.

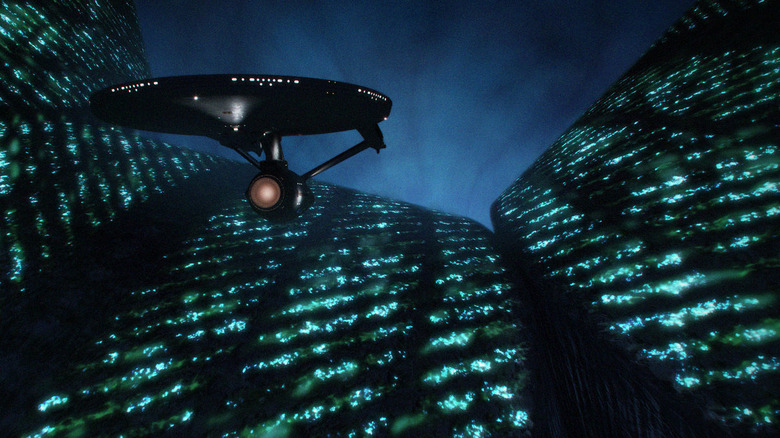

Crunch Time on the Enterprise

While Trumbull was working on Showscan in 1977, he was approached by Paramount Pictures to work on the special effects for the recently greenlit "Star Trek: The Motion Picture." Because of his work on "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," and because he was preoccupied with Showscan, Trumbull had to turn the job down. The story goes that Paramount was so incensed that Trumbull turned them down that they vengefully slashed the budget of his effects studio, essentially shuttering it. Paramount instead hired the effects house Robert Abel and Associates, best known for TV commercials, to invent cutting-edge CGI effects for the movie. Abel worked furiously for months, but continued to fail, unable to produce the kind of special effects needed. Late in production, Trumbull even offered to come on at the last minute to help out, but Paramount still refused.

Early in 1979, principal photography was completed on "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," and Abel still hadn't produced a single second of usable CGI footage. With only six months until release, Paramount finally acquiesced, and hired Trumbull to take over production. Trumbull, working with a relatively small, already-built model of the U.S.S. Enterprise, started churning. He added some more slit-scan photography, added as much detail as he could to the Enterprise, and made a damn decent-looking movie; It would be hard to tell that the effects in "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" were produced with such a tight turnaround. For Trekkies wanting an epic look to a previously rinky-dink 1960s TV show, "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" delivered, adding an enormous sense of scale to the ship and to the show in general.

Trumbull said that the six month, 24-hour-a-day job left him in the hospital with ulcers and exhaustion. 650 FX shots in six months, man. That's as many as in "Close Encounters" and "Star Wars" combined.

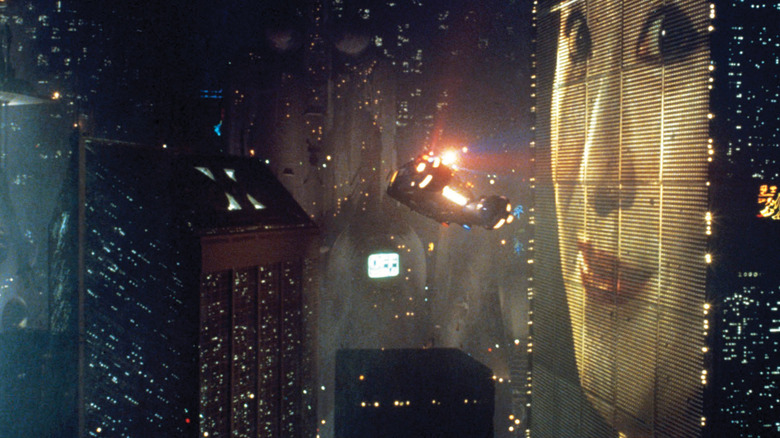

Dreaming of Electric Sheep

The experience on "Star Trek" left a sour taste in Trumbull's mouth, and he had promised himself that he would only work on his own projects from then on out. Working on Hollywood productions was interrupting his own work on Showscan and other film technologies, and fighting with studios and directors was not something he was interested in doing any longer. He reneged on his promise, however, to work on Ridley Scott's 1982 sci-fi masterpiece/box office flop "Blade Runner." Trumbull said that he was tired of working on black spacescapes and starships, and "Blade Runner" was a chance to work on more Earthbound settings. "Blade Runner" is set on Earth in the year 2019, and Los Angeles was meant to look like a city-sized oil refinery. Trumbull added electronic billboards to the landscape as well, creating the film's signature look.

The story goes that Trumbull was unhappy working on "Blade Runner" as well, however, and a lot of his newer team members were too green to work as professionally as he had liked. There was even a (non-disastrous) fire on the effects lot that slowed production. Trumbull's visuals were striking and have since gone down in the annals of sci-fi filmmaking as among the most legendary and influential, but Trumbull was eventually fired from the production, unhappy with Hollywood.

In the wake of "Blade Runner," Trumbull tried once again to get Showscan off the ground with a film called "Brainstorm," which he directed, but studios and theaters balked at the idea of needed new projectors to exhibit it. What's more, star Natalie Wood died during production, and the film experienced so many delays that the studio making it, MGM, wanted to shelve it. Trumbull insisted on finishing it, but MGM got angry at his insistence and wouldn't let him on the lot after a while. "Brainstorm" was released on traditional 35mm film, and was also a bit of a flop. Trumbull effectively left Hollywood after that.

A Return After 30 Years

Trumbull spent the next 30 years happily inventing filming techniques and working on revolutionary effects technology, mostly used on theme park rides and tech exhibitions. He was briefly president of IMAX as well. In the late '00s, however, Trumbull was approached by director Terrence Malick, another Hollywood luminary who took a long hiatus from the business, to work on his film "The Tree of Life." Malick, as one knows from watching his films, is a filmmaker fond of organic visuals and the textures of the natural world. The modern, CGI-based effects houses didn't have the chops to make the kind of visuals that Malick wanted, so he went old school. Trumbull was hired as an effects consultant, and he was allowed to resurrect all the old camera techniques he had mastered over 40 years. The effects in "The Tree of Life" were all discovered organically, with many effects shots being created in-camera, using oils and lens streaking to achieve a unique look. This sort of process resurrection hardly ever happens in Hollywood.

"The Tree of Life" was an enormous and satisfying success for both Trumbull and for Malick, and it has been called — by no less than Roger Ebert — one of the best films of all time.

Trumbull was never not inspired to keep moving forward. He was fascinated with 3D technology, and had worked on new high frame rate process, called Magi, that allowed 3D technology to work better. He wanted to shoot a film entirely in miniature. His Showscan process was even partially realized by James Cameron, who incorporated some of his ideas into his long-in-production "Avatar" sequel.

Trumbull died on 7 February, 2022. His visuals will forever live in our imaginations, allowing us to cling onto something both real and extraordinary. Rest in peace.