Schindler's List Ending Explained: A Harrowing Reminder And A Stark Warning

Living in the Czech Republic, the Holocaust and its aftermath feels far more present than it ever did while I was growing up in the east of England. There, many people still indulge themselves in a weird nostalgia for the half-imagined World War II of Vera Lynn crooning about bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover; dashing fighter pilots in blazers scrambling to their Spitfires to thwart the Luftwaffe; and bravely battling insurmountable odds until the Americans decided to show up.

Down the road from my apartment in Brno, there is a small park with a monolithic fountain dedicated to the city's Roma and Jewish citizens who fell victim to the Nazi regime. In the summer, you will often see young Romani children swimming in its waters, oblivious to the horror in their people's heritage that it commemorates. In 2015, the city marked the 70th anniversary of the end of the war with an apology for the Death March, where thousands of Germans were expelled from their homes and forced to walk to Austria. Along the way, many died before they even reached the border (via War History Online).

Around 30 miles north of Brno is Brněnec, where Oskar Schindler relocated over a 1,000 of his Jewish workers to his munitions factory, saving them from the extermination camps as the Third Reich fell to Allied forces.

With all these stark historical reminders reaching into the present, it's definitely not the stuff of bulldog spirit and sticking it to Hitler with his one ball, as the old British marching song goes.

I was 16 when "Schindler's List" came out, and our history teacher took the whole class to watch it at the cinema. We'd studied the Holocaust all term and the film brought those fuzzy old black-and-white photos from our textbooks to vivid life, and I was shocked and deeply upset. But I was also grateful to director Steven Spielberg for finding a note of hope amid all the unimaginable terror to make the film watchable, and it awakened me to both the atrocities of the Holocaust and wider prejudices suffered in the modern era, such as the genocide of Bosnian Muslims a few years later.

"Schindler's List" was a landmark film, a box office success that earned Best Picture at the Academy Awards and won Steven Spielberg his first Best Director Oscar. But it's also credited with bringing the Holocaust to a wider audience. Yet for all its acclaim, the film also received backlash and criticism, particularly regarding its ending and epilogue.

Let's take a look at that double-ending in a little more detail.

So What Happens in Schindler's List?

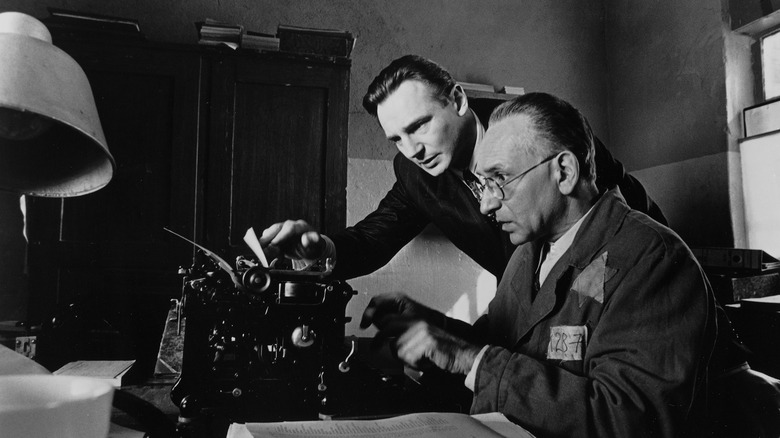

"Schindler's List" opens in 1939 after the Nazis defeat the Polish army and force Krakow's Jews to register and move into a cramped ghetto. We then meet Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), a German industrialist who, at first glance, seems an unlikely savior. He's a womanizing, hard-drinking Nazi party member who rolls into town viewing the war as a great way to make a fortune for himself. Through a mixture of tenacity, flattery, and bribery, he earns the favor of the local Wehrmacht and SS officials and sets up shop in an old factory, planning to produce enamelware using the abundant source of cheap Jewish labor. To this end, he employs Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), a shred member of the Jewish council, to act as his accountant and help him establish contact with key figures in the community and get his business under way.

Skip forward to 1943, when SS man Amon Göth (Ralph Fiennes) arrives in Krakow to oversee the construction of a labor camp in the nearby Płaszów district. He rules over the camp with a cruel hand, arbitrarily shooting workers from the balcony of his villa, and is troubled by his feelings for his Jewish maid, Helen Hirsch (Embeth Davidtz).

After Schindler is profoundly affected by witnessing the brutal liquidation of the ghetto, he befriends Göth and offers bribes to carry on using his workers – now Göth's prisoners – and build a sub-camp for them near his factory. While Schindler's workers are treated significantly better than the other unfortunate Jews in Göth's camp, they are still not safe when the Nazis begin to implement the Final Solution and order all the city's remaining Jews to be shipped to Auschwitz.

Schindler approaches Göth with more bribes, paying a fee to keep each of his "skilled" workers and move them to the security of a new camp in the Sudetenland region of occupied Czechoslovakia. Schindler and Stern draw up a list of all the people he can afford to save, but a clerical error sees all his women and children redirected to Auschwitz...

The Final Scenes of Schindler's List

The women and children's terrifying experience in Auschwitz, including the horrifying moment when they are herded into the showers naked, fully expecting to be gassed, plays a little like a typical Spielbergian suspense moment as the film's dramatic peak. Yet it really happened, although their gruelling ordeal was drawn out far longer in real life; before shipment to Schindler's new factory, the men went to the Gross-Rosen camp for inspection while the women were sent to Auschwitz. It took a month for them to be recovered, during which some were "lost in the system." In the film, Schindler went to rescue them himself, while the real Schindler dispatched a secretary instead.

The real-life Schindler had little to do with the drawing up of the famous list (via History Collection), which was a merger of lists drawn up by other co-conspirators, including Marcel Goldberg, a Plaszow camp orderly.

After the women and children are reunited with the men in Schindler's new camp, we move into the film's conclusion. Schindler bans Nazi soldiers from the factory floor and forbids summary executions, allowing his workers to resume some sense of normality and encouraging the rabbi to observe Sabbath.

Now supposedly manufacturing munitions, a rumor emerges that Schindler himself is sabotaging the production line. As Stern fears that they might get caught and shipped back to Auschwitz, Schindler resolves to buy weaponry to pass off as their own. A caption tells us that in seven months of production, Schindler spent millions of Reichmarks sustaining his workers and bribing officials.

As the war comes to an end, Schindler announces that at midnight he will be a criminal, as a Nazi party member and a profiteer. Knowing the German soldiers have received instructions to kill the workers, he invites them onto the factory floor and gives them the chance to fulfill their last orders or return to their families as men. Every last one takes the second option and quietly leave.

Schindler prepares to make his midnight getaway and receives a letter signed by all the workers in case he is caught. Stern presents him with a gold ring, bearing an inscription from the Talmud: "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire."

It's a perfect tagline for the film. Schindler breaks down, devastated that he couldn't have saved more, realizing that his car could have bought 10 more people, his Nazi lapel badge another two, one at least...

After a group hug, Schindler and his wife swap their fine threads for prison uniforms and flee. In the morning, the workers are liberated by a Red Army soldier, who points them in the direction of a nearby town. The last black-and-white sequence of the film shows them walking across the fields, before we dissolve into the color epilogue.

Here, we watch the actors and their real-life counterparts file past, laying a stone on Schindler's grave in Jerusalem as a mark of respect. Lastly, in a somewhat melodramatic touch, the shadow of Liam Neeson falls across the tomb, placing two roses.

Backlash Against Schindler's List

For all its undoubted historical and cinematic importance, "Schindler's List" received backlash from many critics and scholars, with their ire particularly reserved for its denouement. Criticism varied from the film representing a "Good German" narrative that perpetuated Jewish stereotypes to sexualizing their suffering, specifically Embeth Davidtz's wet t-shirt moment when Helen Hirsch's bath time is interrupted by Göth (via The Jewish Chronicle).

Some of the more mean-spirited criticism leveled at Spielberg suggested that he was only making the film to win an Oscar. Spielberg, who had suffered Anti-semitic bullying while growing up and lost family members during the Holocaust, roundly rejected such claims. As he told the New York Times:

"There is nothing self-serving about what motivated me to bring 'Schindler's List' to the screen. I don't give any credit to other people's cynicism."

Universal acquired the rights to "Schindler's Ark," Thomas Keneally's source novel, over 10 years earlier, but Spielberg put off directing the picture because he worried that he wasn't mature enough to do the subject matter justice. Roman Polanski and Billy Wilder were two directors in the frame to make the film before Spielberg finally shot the film in early 1993. He lists his motivations for making the film as many-fold, including the necessity of providing a document of educational value, the rise of Neo-Nazism and Holocaust denial, and concern that the Holocaust survivors were ageing and might pass away before they had chance to tell their stories. The success of "Schindler's List" also allowed him to found the USC Shoah Foundation.

Despite this, the perceived Hollywood-ization of the Holocaust had its critics, as did the hopeful note that I so appreciated as a teenager for getting me through the film. Dr Nathan Abrams wrote in The Jewish Chronicle:

"Spielberg portrayed them [the Jews] as cardboard cut-outs, a monolithic mass of feebleness, lacking in psychological depth, to be saved or murdered at the whim of the non-Jews. From this point of view, then, Schindler's List is not about the Holocaust or the Jews at all, but a biopic of Schindler and his conversion from ambivalent antihero to righteous gentile."

He also took exception to the color epilogue:

"Meanwhile, on the soundtrack plays Yerushalayim Shel Zahav (Jerusalem of Gold), a post Six-Day War song, written 22 years after the Holocaust, and describing the Jewish people's 2000-year longing to return to Jerusalem. The song inscribed the film with an irrelevant Zionist, even religious narrative."

Critic J. Hoberman witheringly described the film as "a feel-good movie about the ultimate feel-bad experience" (via LA Times), while Omer Bartov, Distinguished Professor of European History, also battered its conclusion:

"Since it is a Hollywood production, 'Schindler's List' has a plot and a 'happy' end. Unfortunately, the positively repulsive kitsch of the last two scenes undermines much of the film's previous merits. Up to this point, Spielberg's intuition led him in the right direction, even if it went against the apparent (Hollywood) rules of his trade... But his desire to end the film with an emotional catharsis and a final humanization of his hero, coupled with his wish to bring the tale to a proper Zionist/ideological conclusion, once more raises doubts about the compatibility between the director and his chosen subject."

The Enduring Popularity of Schindler's List

Several years after "Schindler's List” was released, I visited Auschwitz with my girlfriend on a bitter snowy February day. I had a filthy cold and I was absolutely dreading it. Yet, as we walked through the various exhibits, I just felt totally numbed by the catalogue of horror on display. Silence emanated from the black-and-white photos on the wall and even the camp's most graphic "highlight," a glass case piled high with greying, matted hair cut from countless victims, left me cold. When we first laid eyes on it, I instinctively reached across to feel my girlfriend's hair, trying to gauge how many people's sheerings were in there. But still I couldn't connect.

What finally brought a sob from my throat were the shoes. Among the hundreds of dusty, forlorn pieces of mismatched footwear was a single red child's sandal. Judging by the size, it must have once belonged to a girl aged three or four.

Of course, I was making the connection to the famous scene in "Schindler's List," where the little girl in the red coat makes her way through the carnage of the ghetto liquidation unscathed only to reappear later, dead, on a barrow-load of corpses. It is perhaps the film's most gimmicky, Spielbergian moment, but it is undeniably powerful. The real Schindler never experienced such an on-the-spot epiphany (via History Collection), his transition from avarice to altruism far more ambiguous, yet the scene takes liberties with the truth to distill the enormity of the Holocaust into terms we can relate to.

That's the emotional impact of "Schindler's List." While I fully appreciate the criticism leveled against it, would I have even spotted the red sandal among all those other shoes and made such a human connection to the unthinkable tragedy without Spielberg's film?

Spielberg's choices – the girl in the red coat, the color epilogue – bring the past into the present in a way that few films about the subject have managed, before or since. Claude Lantzmann's "Shoah" may be regarded as the definitive Holocaust film, but who among the general movie-going public has the endurance to tackle its nine-hour duration? Even as a serious lifelong film buff, I still haven't seen it. I plan to take a run at it in the future, but realistically, I'll probably see "Schindler's List" again before that day comes.

Ultimately, it took a director of Spielberg's fame and clout to make a film about such a harrowing subject that people actually wanted to watch. Surely that must only be a good thing, especially when you consider that a recent survey revealed that an astonishing two-thirds of Americans aged 18-39 were unaware that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (via The Guardian). For its perceived faults, Spielberg's popularity will ensure that "Schindler's List" endures on TV schedules and gets passed down from generation to generation as a reminder, and a stark warning.