The French Connection Ending Explained: The Cop Thriller Grows Up And Gets Real

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Most directors like to end their films with a succinct, direct and conclusive statement. William Friedkin, however, would much rather his audiences leave with lingering, often disturbing unanswered questions in their minds. From the uneasy finale of "The Exorcist" (which has had multiple endings released) to the haunting conclusion of "Sorcerer," Friedkin is clearly drawn to ambiguity, making his films mysteries not in a narrative sense but in a thematic one. His commitment to finding the reality within fiction means that his endings are rarely comfortable, neatly constructed summations.

Audiences watching Friedkin's "The French Connection" when it was released in 1971 were likely expecting a gritty cop thriller, a subgenre that up to that point typically featured clear-cut resolutions: This character committed the crime, they're either captured or killed, and so on. Friedkin's film would refuse to allow its audience or its characters such an easy conclusion, presenting an ending that still disturbs and invites debate to this day.

The French Connection is based on true events

"The French Connection" is far from the first cop movie to adapt a real-life case, but it is one of the first to take its true events to heart. The film is based on a narcotics case run by New York City Detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso in the 1960s. Their pursuit of a drug kingpin named Jean Jehan made headlines both in NYC and abroad, the case becoming infamous not just for the number of countries involved in the smuggling ring but for the fact that Jehan was never brought to justice. In addition, Egan and Grosso's methods came under scrutiny, one of the first times that members of law enforcement were seen as stepping outside the boundaries of the law.

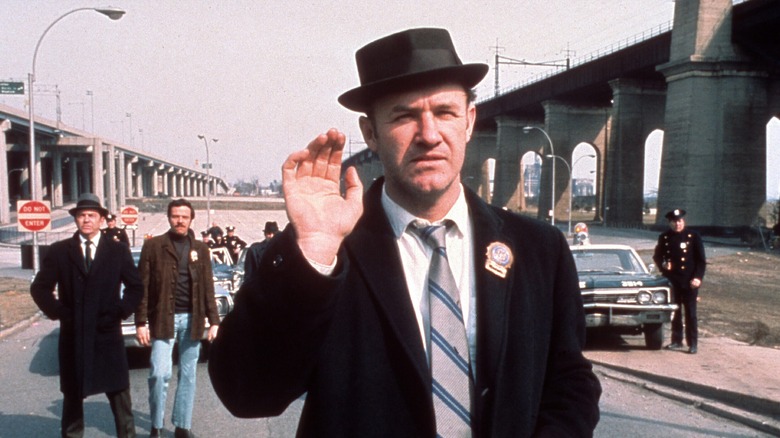

Friedkin's film, adapted from Robin Moore's nonfiction account of the case, presents Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle (Gene Hackman) as the Egan analogue and Buddy "Cloudy" Russo (Roy Scheider) as Grosso's counterpart, with Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey) standing in for Jehan. The film shows how Doyle's obsessive and unending need to bust criminals drives him and his partner to a random stakeout of a small time dealer, Sal Boca (Tony Lo Bianco). As the detectives study his activities, they learn that Boca is involved in a deal with Charnier, a Frenchman who is the major source of heroin imported into NYC. Russo and especially Doyle turn the city upside down following Charnier and his partners, with Doyle's pursuit of an assassin of Charnier's resulting in one of the most famous (and dangerous!) car chases in cinematic history.

Throughout, Friedkin and his cast demonstrate how Doyle's actions are increasingly unhinged and borderline criminal. Grosso is about the only person in the department who's willing to work with Doyle; FBI agent Mulderig (Bill Hickman) nearly comes to blows with Doyle over a past incident where the detective got one of his fellow officers killed. The character of Doyle, a casually racist misanthrope with serious anger management issues, was blisteringly new to the cop thriller, a heavily flawed character that echoed film noir protagonists more than hero cops. It was a sign that the subgenre was evolving as it more closely emulated real life.

Who did Popeye Doyle shoot at the end of The French Connection?

The big break in Popeye and Cloudy's pursuit of Charnier comes when they stakeout a car seemingly owned by one of the Frenchman's associates, a TV host named Devereaux (Frédéric de Pasquale). After literally tearing the car apart in the NYPD garage, the detectives find 120 pounds of heroin hidden in the rocker panels. They then reassemble and return the car to Devereaux, who hands it over to Charnier, refusing to carry on with their prior plan to unload the car and its merchandise. Charnier himself travels with the car to the meet, which is held on the deserted Ward's Island. The exchange goes smoothly, but as Charnier is leaving with his money and Boca's gang are preparing to leave with their heroin, Charnier's car is blocked by a phalanx of NYPD vehicles fronted by Doyle himself, who gives a knowing wave to his quarry that echoes one given to him by Charnier when the Frenchman eluded him earlier. Trapped, Charnier, Boca, and the rest of the criminals attempt to flee or fight, as Grosso, Doyle and the rest of the force close in for the capture.

Doyle, fully immersed in his obsession and righteous victory, pursues the slippery Charnier into some nearby decrepit buildings, quickly losing sight of him. His prey so close but starting to slip away, Doyle refuses the advice of his partner to break off the pursuit and opens fire on a figure he believes to be the Frenchman. As he runs to claim his victory, he discovers Agent Mulderig, rapidly dying from Doyle's bullet. Cloudy is stunned, but Doyle is unfazed, his mind only on his enemy. Doyle runs haphazardly through the eerie, decaying building, seeing no sign of his quarry but continuing anyway. Rounding a corner, he leaves frame, and a single gunshot is heard before the film cuts to black. Did Doyle shoot at Charnier and miss? Was it Popeye firing in frustration? The ending is ambiguous and perhaps unsatisfactory for some ... but then, that's the whole point.

What is the point of The French Connection?

From the beginning of his movie career, William Friedkin was more interested in the truth than pure fiction. He got his start making short documentary films, and when he moved on to narrative features he brought his documentary approach to drama, creating something he dubbed an "induced documentary" style. That style is all over his early work, and "The French Connection" is arguably the best example of it. Friedkin, in conjunction with cinematographer Owen Roizman, doesn't comment with his camera so much as he lets it capture the characters in their surroundings, allowing both of those elements to do their own commenting. While of course every choice of camera placement and cut is a comment, the style presents the induced feeling of reality happening before our eyes.

That veracity is increased by the distinct lack of typical Hollywood elements in "The French Connection." Characters don't talk about themselves but instead simply behave in front of the camera, Don Ellis' score doesn't tell the audience what to feel when it's present (which is sparingly) but instead evokes a mood, and the ending isn't wrapped in a neat bow. The only conclusion Friedkin allows his audience is a series of curt, cold on-screen postscripts giving a few scant details on where some of the characters ended up after the events of the film. Even here, Friedkin refuses to provide much clarity. We're told that "Alain Charnier was never caught," and Popeye and Cloudy were "transferred out of the Narcotics Bureau and reassigned." The combined gritty, in-your-face drama of the film's events with this distant and chilly conclusion is the emotional equivalent of being drenched in ice cold water, and it drives the point of Friedkin's style and "The French Connection" home — that reality is inconclusive and unfair.

Despite the sequel, the film loses none of its haunting power

"The French Connection's" ending is so startling and uncomfortable that it's no surprise the film's success seemed to beg Hollywood to follow it up with a sequel that attempts to rectify Doyle's crushing failure. Thus, 1975's "French Connection II" was produced, and it's rather nakedly a sequel that attempts to please audiences left frustrated and disturbed by the original film's finale.

In the sequel's defense, it doesn't soften the character of Doyle (a returning Hackman considered it one of his best performances) nor let him have an easy time of it, as he continues his obsessive pursuit of Charnier through a foreign country where he has no assistance, his enemies taking every chance they can to stop him by any means necessary. Still, its ending feels a bit like a foregone conclusion, a mea culpa to those who had expected a more traditional badass cop narrative the first time around. It's also a nod to the fact that the film, along with the "Dirty Harry" series and Clint Eastwood's Harry Callahan character, had birthed a new trope of a rogue cop who breaks the rules and gets results.

Despite the sequel's existence, the lingering and far less pandering conclusion of "The French Connection" couldn't be so easily revised or shaken. Its connection to reality both in fact and feeling helps the ending retain its haunting power. While one can reasonably conclude that Doyle didn't die (by his own hand or another's) given the film's postscript of his transfer, it hardly matters since it's clear that the man's soul has become truly lost. Popeye Doyle crossed the line one too many times, went too far into the abyss, and can never find his prey — or his way back.