The 15 Best Sidney Poitier Movies Ranked

He stood upright, smiled his debonair smile, and signaled to Hollywood that he was too flawless to ignore.

Such was Sidney Poitier's responsibility. He was every good-intentioned white American's Black friend, every hyper-visible good example. He was the chosen one invited to dinner parties and the exception to the assumed rule. But for Black Americans, he was a comfortable myth — not necessarily the Black man they wanted to mimic, but rather the Black man they needed him to be.

Ideally, many would love to remember Sidney Poitier's work as a catalog that consistently challenged the status quo through his groundbreaking artistic presence. Yet, more often than not (and despite his incredible range), he was relegated to stories told through the gaze of white directors, writers, and audiences. His acting work often exalted respectability politics in classics such as "Lilies of the Field" and "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner." However, he found an authoritative voice later in life as the director of movies like "Uptown Saturday Night" and "Buck and the Preacher."

He was an artisan of firsts who paved the way for legendary Black artists ranging from Denzel Washington to Quincy Jones, but that influence often came with a quiet fury earned in the racial dynamics of the times. With the passing of Poitier on January 6, 2022, I've taken the time to rank some of his best films. In truth, they have all benefited from his presence in a way that's stood the test of time.

15. A Raisin in the Sun

Director Daniel Petrie's "A Raisin in the Sun," adapted from Lorraine Hansberry's play of the same name, isn't so much about the Black experience as it is about a single family's experience. Still, it is by no means airbrushed or romanticized. It's also not an interpretation of a people as much as it's a depiction of an age. The film fuses the segregationist policies of Chicago in the 1940s with the reverberations of the Jim Crow era and places all that strife at the doorstep of one Black family.

The play Hansberry wrote in 1959 feels as authentic as a fictional story about racism and upward Black mobility can because it was lived. Yes, the emotional hook was made real through a quartet of legendary performers: Ruby Dee, Diana Sands, Claudia McNeil, and of course, Sidney Poitier. However, as reported by PBS, the heart of this timeless classic comes from Hansberry's own exposure to the racist practices her family faced as they tried to settle into a white neighborhood on Chicago's South Side in 1938.

Unlike her white contemporaries, Hansberry didn't attempt to protect audiences from the uncomfortable reality of a Black man (portrayed by Poitier) who often verbally abuses his wife (Ruby Dee). She didn't romanticize the collective frustrations with a country that would deem them as "less-than." She didn't succumb to the stereotype that Black Americans weren't complex thinkers. "A Raisin in the Sun" is earthbound, painfully human, and one of the best stages on which Poitier could demonstrate his astonishing range.

14. In the Heat of the Night

"In the Heat of the Night" can be summed up in a single scene: Black investigator Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) interrogating an obviously racist murder suspect in Eric Endicott (Larry Gates). Tibbs' manner is grand with a vague air of proud conviction. Words are exchanged, and a question is asked that rubs the white man the wrong way. Given the race of the man before him, Endicott has the mistaken impression that he can slap Tibbs in response.

What comes next requires some context: This was 1967 — a year before Martin Luther King's assassination at the peak of the Civil Rights movement. The idea of Poitier slapping a white actor back for all of America to see was as taboo as Blackface in the 21st century. The move would spark a bevy of conversations related to race and Black autonomy.

Historical significance aside, director Norman Jewison uses a classic framework to explore a moral wrong by casting an outsider into the center of a problem. Poitier as a Philadelphia homicide inspector brought in to investigate a murder in a small, Southern town is a lightning rod, and to this day, it is that slap that defines Poitier's insistence on being what Black America in the '60s needed him to be.

13. The Defiant Ones

There's something to be said for the well-meaning racial reconciliation trope of 1958's "The Defiant Ones" in which an ill-mannered racist finds salvation in the guise of his Black friend. Yet, circumstances afford it a pass. It was the film that earned Sidney Poitier his first Academy Award nomination and also exposed an unknowing audience to racism as a learned behavior rather than a fact of life. Two individuals set in their ways can change through exposure and education.

Directed by Stanley Kramer, "The Defiant Ones" stars Poitier and Tony Curtis as Noah Cullen and John "Joker" Jackson, a pair of escaped convicts on the run in the South. Shackled together, the men initially despise each other, but when they're forced to rely on one another to survive, they grow to be friends. While the message may seem a little on-the-nose for modern audiences, the cultural climate of the late 1950s needed every positive racial message it could get.

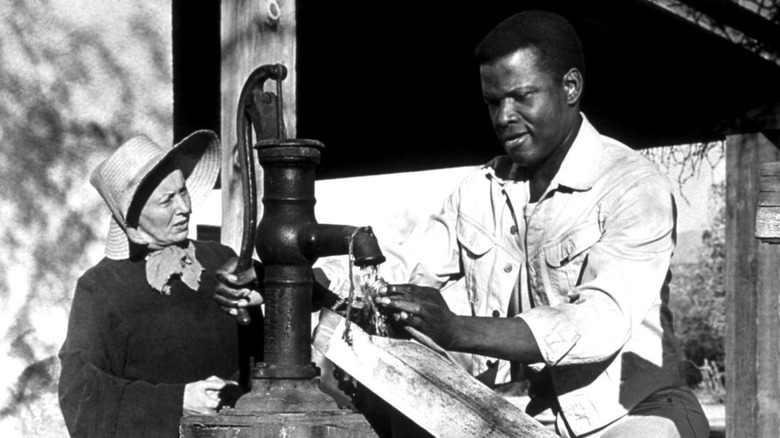

12. Lilies of the Field

"Lilies of the Field" is the kind of movie that strengthened Sidney Poitier's "good Black guy" image in the '60s. The film also garnered Poitier an Academy Award, making him the first Black actor to receive the honor.

Poitier plays a wandering laborer named Homer Smith who comes across a group of German nuns in the Arizona desert. Led by Lilia Skala as Mother Maria, the nuns come to consider Homer a helper sent by God to assist with building a chapel. A certain warm-hearted likeability defines Poitier's performance as he overcomes differences in language and race, and there's a comfortable rhythm in director Ralph Nelson's film. Still, there is an old-school hokeyness in "Lilies of the Field" that is impossible to dismiss.

The problematic parts of "Lilies of the Field” can be forgiven in the context of its time. Again, Poitier plays Hollywood's idealized Black man, and that often bleeds into the "magical negro" trope — a cliché that presents a Black protagonist whose main function is to better the lives of their white counterparts, often at the cost of their own depth and development. Ultimately, the film suffers from the classic issue of the white gaze. For Poitier, however, these were necessary evils. His award-winning performance would pave the way for countless others.

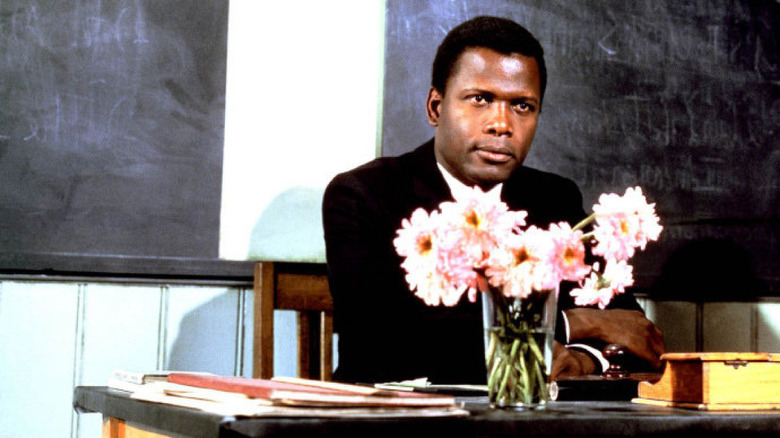

11. To Sir, With Love

The 1960s was a far more forgiving era when plots about teachers who inspire rooms packed with delinquent children could rule the day. Although films such as "Lean on Me" and "Dangerous Minds" have made the teacher-as-savior plot a cliché, "To Sir, With Love" is an early entry (and one of the best) in this now hackneyed cinematic formula and a prime influence on similar films that came after.

Directed by James Clavell, "To Sir, With Love" stars Sidney Poitier as a fresh engineering graduate who can't find work in his field. As an alternative, he becomes a teacher at a school for troubled youth in London. Once again, here's a movie that requires some historical context: Poitier portrays a Black character dispensing life-changing advice to a group of white children in the 1960s. Remember, this was a decade still wrestling with the idea of equality for Black Americans and Londoners. To the film's credit, Poitier's performance is beautiful, textured, and necessary in an era of change.

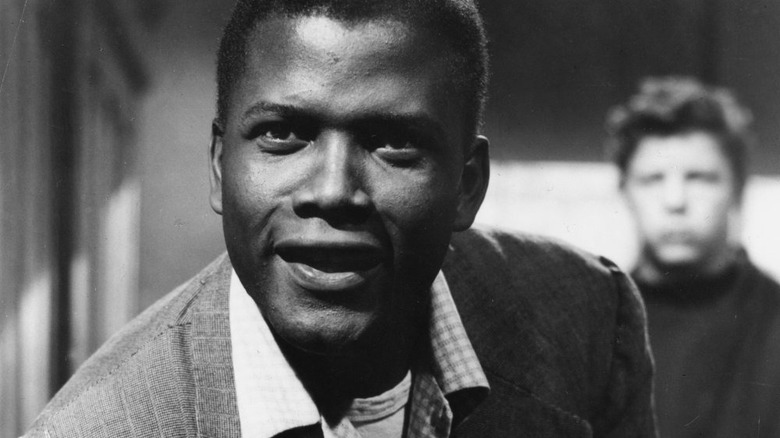

10. No Way Out

The first thing that needs to be considered is the fact that Sidney Poitier was only 22 when he starred in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's "No Way Out." There is nothing in this film for Poitier to romanticize. There isn't a thing for white audiences to find comfort in or get lost in. "No Way Out" represents the march from one relentless depiction of racism to the next, bravely probing protests, violence, and portrayals of antisemitism in an era of racial division.

The film Mankiewicz directed was to the point: A small-time crook named Ray Biddle (Richard Widmark) and his brother Johnny (Dick Paxton) are taken to a public hospital to be treated for bullet wounds they suffered in a botched robbery. Biddle is, of course, a racist, and he decides to aim his bigotry at a new physician named Dr. Luther Brooks (Poitier). This powerful performance was Poitier's very first role, and he took it at an age when many actors might feel unaccomplished by comparison. With "No Way Out," Poitier took every career risk imaginable in the 1950s — a time that punished liberal-minded films, actors, and directors.

9. A Patch of Blue

Sidney Poitier is, quintessentially, a man of firsts. By the time he appeared in "A Patch of Blue," he was already the first Black actor to win an Oscar. Now, he was on his way to becoming the first Black actor to kiss a white woman in a film. While this advancement may seem minuscule to present-day audiences, it nevertheless spoke to a stance that positioned popular segregationist practices as an expiring concept.

In this love story directed by Guy Green, Poitier plays Gordan Ralfe, a courteous office worker who finds romance with Selina D'Arcey (Elizabeth Hartman), a blind white woman (because, of course, her blindness lessens the taboo) who lives with her abusive mother (Shelley Winters). In what could serve as another example of the "Magical Negro" trope, Green instead opts for a story that leans more on a mutual need, distilling a message about prejudice as a disease that can be overcome through a difference of perspective.

8. Guess Who's Coming to Dinner

It almost feels like a cliché to describe a film starring Sidney Poitier as brave. That's a testament to what he came to symbolize through his visibility — a taboo in the face of a white Hollywood gaze.

"Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" introduced the American public to a conflict that seemingly took place in every other household at one point or another: the white daughter who brings home the Black sweetheart.

"Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" is an acknowledgment of an intolerance through the lens of a white perspective. For example, there are moments that involve Poitier lecturing his own Black father about his distaste for interracial marriages. The film refuses to question where that fear may originate for a Black American elder at that time, instead opting to colorblind the nuanced problem. "Your generation will always think of itself as Negro first and a man second," scolds Poitier. It's hardly a movie looking to provide a remedy that aligns with today's politics — we have "Get Out" for that. Still, "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" stands as a film that tackled a conversation that few wanted to have.

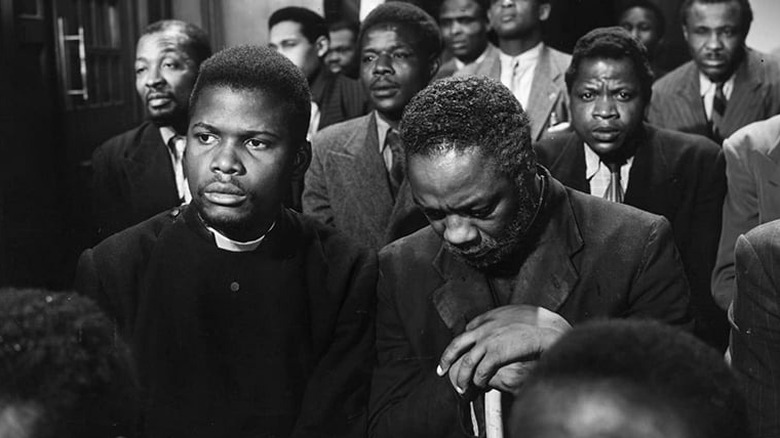

7. Cry, the Beloved Country

It was one thing to tackle issues of race in America, but Sidney Poitier saw fit to involve himself with the impact of apartheid, an institution of racial segregation imposed on South Africa's population from 1948 into the early 1990s. Predating the 1995 adaptation starring James Earl Jones by over 40 years, "Cry, the Beloved Country" stars Poitier as Reverend Msimangu who is searching for his missing son in Johannesburg, South Africa. In his quest, he finds a sister who has turned to sex work and a son who's been branded a thief.

Adapted from Alan Paton's 1948 novel and co-written by John Howard Lawson (a victim of McCarthyism), this British production picks up on an issue that reaches beyond American soil, giving Poitier another vehicle when roles for Black actors stateside were largely limited or relegated to ugly stereotypes. Shot partially in South Africa, the film also features a performance by veteran activist and actor Canada Lee as Stephen Kumalo. "Cry, the Beloved Country" first exposed Poitier to the horrors of apartheid, and, in many ways, informed his future views concerning activism.

6. Porgy and Bess

Let's be perfectly clear by stating that the whole vibe around the musical "Porgy and Bess"— whether it's the 1935 play or the 1959 film adaptation — is a mess of bad optics. However, consider that its origins are in a time when it was an act of progress to accept an exclusively Black cast over a white cast in Blackface. In the film, Porgy (Poitier), a disabled beggar, finds a romance with a drug addict named Bess (Dorothy Dandridge), the girlfriend of local tough guy Crown (Brock Peters). The legendary Sammy Davis Jr. plays a coke dealer to boot! For many years, it was nearly impossible to see "Porgy and Bess." As reported by the Los Angeles Times, the film was out of circulation for decades, airing on network television just once in the late 1960s.

What "Porgy and Bess" gets right, however, comes in its the exaggeration of everything between the musical numbers. The talent on display is peerless with the legendary voices of Pearl Bailey, Leslie Scott, and Scatman Crothers (Poitier lip-synced his way through this one with Robert McFerrin handling Porgy's vocals).

While "Porgy and Bess" may be the product of a less sensitive time in the thick of stereotypical Black themes, the talent on screen is still undeniable.

5. Stir Crazy (As Director)

It takes a certain finesse to squeeze equal measures of wackiness out of Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor. Yet, Sidney Poitier manages to do just that with "Stir Crazy." Before "Stir Crazy," Poitier had already had experience in the director's chair beginning in the 1970s. His first project was 1972's "Buck and the Preacher" which he followed with the comedy "Uptown Saturday Night" in 1974. In another first for Poitier, "Stir Crazy" was the first R-rated comedy by a Black director to earn over $100 million.

In the film, down-on-his-luck playwright Skip Donahue (Wilder) pairs up with weed-smoking caterer Harry Monroe (Pryor) for a trek to LA. A series of unlikely circumstances occur, and both are framed for an armed robbery in hilarious fashion. There's a reversal of expectations with both actors: The normally passive Wilder extends his range with a deranged mania. Pryor is anxious and tense instead of his typically confident self. Ordinarily, this whole jumble of attitudes wouldn't work, but Poitier's knowledge of the beautiful dynamic between the two helped make "Stir Crazy" an undeniable comedy classic.

4. Sneakers

The signature trope of a good heist movie movie is gathering a bunch of people who are really great at one thing (none of which involves a healthy life balance) to steal something valuable. Directed by Phil Alden Robinson, "Sneakers" features the legendary personalities of Sidney Poitier, Ben Kingsley, Dan Aykroyd, Robert Redford, and David Strathairn as associates in a counter-security firm in San Francisco. In one way or another, each professional is an outsider in their specialty, whether it is burglary, surveillance, or hacking. "Sneakers" brings all the vibes of a heist movie but with characters who don't immediately intend to commit a heist in said movie.

The characters in the film are professionals who have spent their careers penetrating security systems with relatively boring "sneaker skills." So when one character flirts with a new, sexy, shadowy job, everyone leans into the trope without specifically embodying it. It's a level of genre-juggling that works within the framework of a heist film — dudes with a job to do — while working in a long, self-reflective, and comedic narrative through protagonists who are not necessarily interested in riches or power.

3. Blackboard Jungle

While "Blackboard Jungle" was one of the many early films that allowed Sidney Poitier to showcase his range, he was still limited by storytellers who favored respectability over the truth. In the film, a gang leader by the name of Artie West (Vic Morrow) terrorizes Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford), a fresh-fish teacher who has just taken a job at a tough inner city school. Dadier turns to troublemaker Gregory Miller, played by Poitier, to rein in the out-of-control student body. In that effort, Poitier once again plays up to the Black tradition of characters who side with institutions in power, electing for an answer that deserves a far more complex solution.

As it's been said, Poitier was an actor who often worked with what the era gave him. His representative status during a time with few like himself, in a way, required a certain suppression of the truth. And with this in mind, director Richard Brooks used "Blackboard Jungle" to explain away at-risk youths as one-dimensional delinquents looking for trouble. Sure, it didn't take away from Poitier as an actor or as a contributor of Black excellence, but it's also an example of the frustrating limitations he undoubtedly worked with over the years.

2. The Slender Thread

Directed by Sydney Pollack, "The Slender Thread" from 1965 positions themes of sexism, mental health, and isolation within the confines of a telephone call. Anne Bancroft plays a woman looking to take her own life by way of a deadly overdose of sleeping pills. Shortly before acting on her decision, she calls a crisis hotline only to come in contact with student volunteer Alan Newell (Sidney Poitier) whose job is to keep her on the line long enough to be tracked down and saved.

Like many films from the 1950s and 1960s, "The Slender Thread" begins with well-intentioned ideas but crumbles under current-day scrutiny. For example, the depiction of race as meaningless for two people from a period of stark differences is especially problematic. Despite this, the film is still a classic cinematic lesson in how a suspenseful story can be told through simple, one-to-one dialogue. Yet, there is a missed opportunity within the converging perspectives of a white woman and Black male protagonist from this era. Instead of challenging and interrogating each other's worldviews in an effort to save a life, it relies on surface-level, colorblinded ideas. Still, it was commendable for its time.

1. Buck and the Preacher

You'd be forgiven for thinking that Black Americans had no role in the Wild West, and you'd also be dead wrong if history has anything to say about it. As thoroughly explored by the New York Times, they've largely been omitted from conventional representations in a way that doesn't break even with the truth.

In the classic antebellum Western "Buck and the Preacher," Sidney Poitier stars as Buck, a retired soldier who finds himself escorting wagon trains of Black settlers for income. The equally renowned Harry Belafonte co-stars as Reverend Willis Oaks Rutherford, a faux God-fearing con artist who partners with Buck. When white raiders target the settlers, Buck's mission moves from escorting to protecting the wagon trains using any means at his disposal.

This was Poitier's directorial debut. In many ways, this was a legend bringing friends like Ruby Dee into the fold within the context of a Western vehicle. Although the film is still obsessed with white Western iconography, there are no protagonists making villains out of the Native Americans here. "Buck and the Preacher" is a Western with some necessary explorations of the racial kinetics that shaped the real West.