One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest Ending Explained: Breaking Out Of The System

Miloš Forman's 1975 film "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" is a harrowing tale of rebellion vs. conformity, maturity vs. immaturity, and the true nature of how we measure and treat mental illness. It's about the broken penal system, personal pain, trauma, authority, and freedom. It was viewed as a comedy upon its release: Vincent Canby of the New York Times called it a comedy that cannot support its tragic ending, and Roger Ebert, when he first reviewed the film, felt that the film's overall tone was too light to tackle some of its larger themes. Ebert eventually reassessed the film, including it on his Great Movies list.

Ebert's change may also reflect the general public's changing view of the film. While it was immediately recognized by many as a great work of art — it was an Oscars darling — many have come to see "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" less of a subversive comedy about playful rebellion and more a contemplation of control and chaos as it plays itself out in the woefully underfunded mental health facilities in the United States.

The ending of "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" is unambiguously tragic, however.

McMurphy's Folly

"One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," based on the 1962 Ken Kesey novel, and is one of only three films to win the "big five" Academy Awards; That is: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Lead Actor, Best Lead Actress, and Best Screenplay (and, for the trivia buffs, the other two are 1934's "It Happened One Night" and 1991's "The Silence of the Lambs").

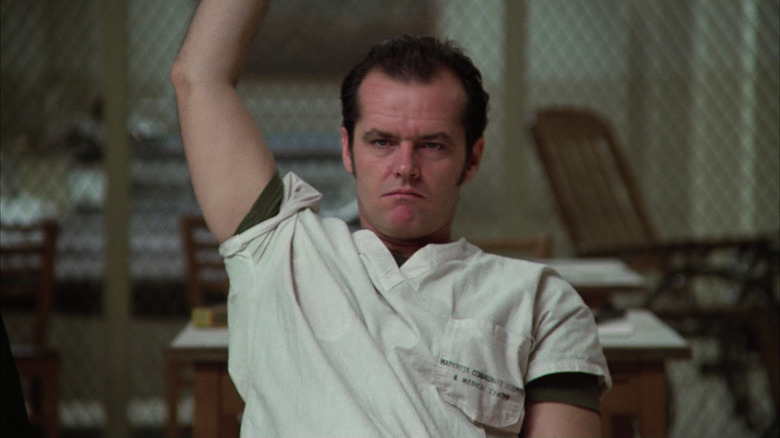

The film is about R.P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) who is sentenced to hard labor in an Oregon prison (we'll learn later that his crime involved the phrase "She looked 18."). In what he thinks is a clever move to avoid said hard labor, McMurphy argues instead that he is mentally ill and is transferred to a mental hospital where he will stay with other live-in patients, played by the likes of Christopher Lloyd, Danny DeVito, Michael Berryman, and Oscar-nominee Brad Dourif. He assumes the hospital will be cushy and posh, but instead finds it forbidding, harsh, and overseen by the stern nurse Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher) who is immediately distrustful of McMurphy's overt sense of masculine chaos.

McMurphy is immediately suspicious of the hospital's therapy techniques. He doesn't like the gentle music, the touchy-feely language. He sees patients that are shy and fearful, and he feels that they only need to go on fishing trips, play pranks, and talk to women in order to "come out of their shells." And, no, "Cuckoo's Nest" is not enormously accurate when it comes to psychology.

The conflict between McMurphy and Ratched is mutually destructive. She attempts to force McMurphy into line by enforcing routine and order into his life — something that the other patients in the hospital arguably require — and he pushes back by introducing more disorder and playful chaos, forcing patients to leave the hospital on a fishing trip, to play basketball, to loosen up, to accept the energy and joy in life — something else that some of the patients arguably require ... with at least one notable exception.

It could be argued that either McMurphy or Nurse Ratched are the villain of the piece.

McMurphy's Rebellion

But we don't see the folly when we look at McMurphy. At least not right away. We see, instead, his rebellion. "Cuckoo's Nest" has long stood as a parable for rebellion and our need to break out of harsh systems. And "Cuckoo's Nest" expertly employs archetypal images of oppression to accomplish it. Nurse Ratched looks like a schoolmarm, a mean parent, a military drill instructor. The hospital is replete with mesh screens, locked windows, harsh lighting, right angles. It looks like a combination prison and public school. The very iconography invites feelings of rebellion in the audience, and McMurphy — the playful, rule-breaking imp — is immediately our stand-in.

The adolescent rebellion in McMurphy appeals to the adolescent in all of us. He encourages the inmates to reject the establishment and to indulge in sports, parties, and sex. McMurphy is attacking the power of female authority/behavior with traditional male "acting out." Ken Kesey wrote his novel in the early 1960s as a direct attack on the authoritarian habits of established medical institutions and, by extension, the authoritarian habits of the world at large. By the mid-1970s, director Forman — a student of the Czech New Wave, and I recommend his 1968 film "The Fireman's Ball" — brought a mellower attack, approaching the book with good humor and a sense of fun. And there is a lot of fun in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

Until there isn't.

McMurphy's Fall

McMurphy's actions, however, don't equal freedom. Nurse Ratched may represent authority, but she also represents maintaining vital order for a group of mentally ill patients who require stability. McMurphy's acting out eventually leads to what is essentially an all-night orgy, a party that triggers a trauma response in Billy Bibbits (Dourif), one of the patients. Billy dies by suicide.

McMurphy is broken down. He is given shock therapy. He is kept in line. But his rebellion that audiences so cheer is also a damaging force. He herds his fellow hospital inmates to go on a boat trip, and we get the sense that they don't all rightfully know what is happening. He asks if he can watch the World Series on TV, but Nurse Ratched insists on a vote. Do the inmates fully comprehend on what they are voting? Ratched is a hard authority figure and is typically received as a cinema supervillain (to the point where she got her own villain origin story TV series), but — and this may be a result of my advanced age — the more I see the film, the more she appears as a sympathetic figure who is only trying to rein in an agent of chaos who threatens to — and ultimately does — do damage to the patients.

Ratched punishes McMurphy. She gives him shock treatment. By the end of the "Cuckoo's Nest," we have seen Ratched rejecting her administrator's suggestion that McMurphy be returned to prison, and we have seen him lobotomized.

Will Sampson

The emotional catharsis comes in the form of "Chief," played by the great Will Sampson. Chief has suffered some previous trauma, and now prefers to remain non-verbal and withdrawn. He doesn't even move a whole lot. McMurphy initially feels that a man of his size — Will Sampson was 6'7" — should be able to break out of the hospital with ease, and even suggests a way one might do so; by ripping a hydrotherapy fountain out of the hospital floor and throwing it through a window. When McMurphy tries, he fails.

McMurphy's constant attempts to bring the patients "out of their shells" does, at least, reach one man. Chief ends up talking to, and trusting, McMurphy, grateful for the change that has been brought into the hospital. At the film's end, Chief finds McMurphy in bed in the middle of the night, and he attempts to talk. Chief finds that McMurphy has been lobotomized. Chief smothers him with a pillow, and then finally rips that hydrotherapy fountain out of the floor and throws it through the window. This time, McMurphy's suggestion worked. The other patients, when the hear the crash, get out of bed, and cheer him on and Chief leaves the hospital.

McMurphy's rebellion did damage, but also aided at least one man in breaking out of the system — quite literally.

Whether you take "Cuckoo's Nest" to be a poem about rebellion or liberation, or a dark tale of how rebellion is ultimately a self-defeating system — no punk rockers live a long time — might depend on your age when you encounter it. I encourage long term re-visitation of "Cuckoo's Nest," as you'll find it changes as you do. No matter what you take away, you'll take away something, which is a mark of a great film.