The Real Life Inspiration Behind The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

Wes Anderson's fourth feature film "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou" follows the story of the titular oceanographer, portrayed in all his idiosyncratic glory by Bill Murray, as he embarks on a "Moby Dick"-esque vendetta against the jaguar shark that ate his partner Esteban. With its colorful cast of characters and magical use of stop-motion animation, the film's vivid visual palette plays host to one of Anderson's most heartfelt tales even as it builds on his penchant for transforming the ordinary into something magnificent.

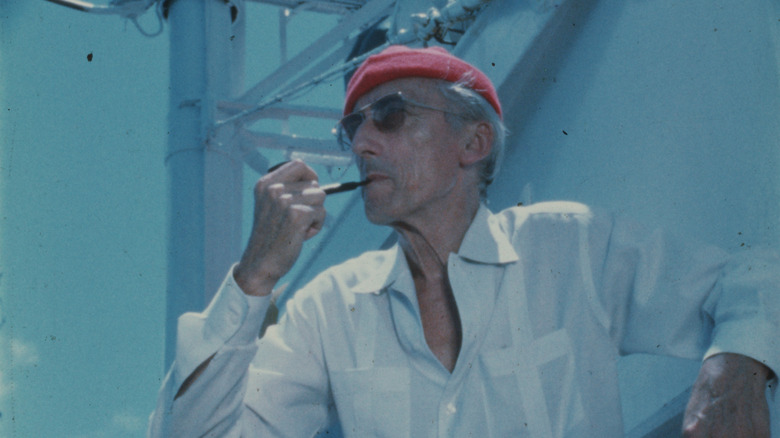

But while the characters that fill "The Life Aquatic" are as delightfully odd as previous Anderson films, there is no doubt all that wonder flows directly from Zissou and the phenomenal man who inspired him. In many ways, the film is both touching parody and eulogy to Jacques-Yves Cousteau, a renowned French filmmaker, scientist, photographer, author, and researcher who spent his life — like Zissou — studying the sea. With a National Geographic documentary about the adventurer titled "Becoming Cousteau" released just last year, the time is ripe for anyone who found themself mesmerized by the world Zissou's world to brush up on the very real life of Cousteau; one that was just as magical and tragic as the film's ode, if not more so because it actually happened.

Early Diving Pioneer and Inventor

Anderson, who admired Cousteau as a child, based Zissou's life on the adventurer, down to his red beanie and iconic blue outfit. Born in Saint-André-de-Cubzac, Gironde, France on June 11, 1910, Cousteau's relationship with the ocean began young, after an automobile accident that broke both his arms ended his future in naval aviation. In order to recover, he was instructed to swim regularly — a regimen that spurred a passion. This put him on a collision course to innovate modern diving, leading him to do everything from co-create the world's first open-circuit, self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) to correctly predict the echolocation abilities of porpoises.

After World War II, Cousteau's real life become eerily intertwined with Zissou's fictional one. It was then he converted a minesweeper called the "Calypso" into his base of operations for experiments, founded the French Oceanographic Campaigns (FOC), and recruited naval officer Philippe Tailliez and diver Frédéric Dumas as his "mousquemers" (musketeers of the sea); life events that sound like plot points pulled directly from "The Life Aquatic." Later projects read like a sci-fi reel, including the invention of the "diving saucer" SP-350, an experimental vessel that allowed pilots to reach a depth of 350 meters, and the ambitious creation of underwater "villages" that sought to increase the depths at which humans could live beneath the ocean. Throughout his long life Cousteau displayed a near-endless ingenuity, a piece of himself that is affectionately recreated by Anderson in Zissou's charmingly imaginative inventions aboard his own experimental vessel the "Belafonte" — and even the film's iconic yellow submarine is an almost direct replica of Cousteau's.

Cousteau also Lost a Son

Cousteau married French explorer Simone Melchior in 1937 and had two sons: Jean-Michel and Phillippe. As in "The Life Aquatic," which sees Ned join Zissou on the film's adventure after tracking him down, Cousteau's sons also joined him on his exploits aboard the "Calypso." But it was his second son Phillippe that he had a close affinity with, designating him as his successor and co-producing countless films with. But tragedy struck in 1979 when Phillippe was killed in the crash of a PBY Catalina flying boat in Portugal. It's heartbreaking scene dramatized by Ned (Owen Wilson) and Zissou's crash in a helicopter near the end of the film, which also results in the death of the adventurer's son — although it's revealed at the end of the film that Ned was actually not Zissou's biological child. For Cousteau, the loss was devastating and drove him to call upon Jean-Michel, an architect, to fill the void.

Unlike in Anderson's film, the loss was not a galvanizing moment for Cousteau or the people in his life. When his wife died in 1990 from cancer, the aging explorer married a woman he had known before his marriage and with whom he had two children, souring his relationship with Jean-Michel. There would be no reconciliation as in "The Life Aquatic" between Zissou and his estranged son Ned, nor a sense of connection between the people remaining in his life after the loss of his beloved son as in the film. There is no riding into the sunset on his yellow submarine for the real-life Cousteau, who died not long after the fallout, but the charm with which Anderson' captures the life of his childhood hero replaces his tragedy with a tender alternative.

From Overzealous Filmmaker to Marine Conservationist

Like Zissou, Cousteau was a prolific documenter of his experiments, creating more than 115 films and 50 books. His 1956 film "The Silent World," titled after his first book, earned him the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival for the unprecedented colorized look it afforded of the worlds beneath our oceans. The film was not without controversy, however, as it depicted the crew and Cousteau irresponsibly wreaking environmental damage. In one scene, he uses dynamite to clear a coral reef to more easily study its confines — similar to Zissou's childish plan to use dynamite to kill the shark. Another more lasting effect exists in a strain of invasive algae known as "Caulerpa," responsible for growing damage to the Mediterranean ecosystem, that was linked in origin to Cousteau's Oceanographic Museum in Monaco.

Zissou's early zeal for exploration and creating stunning documentaries at the expense of the environment is a piece of Cousteau that appears throughout the film as well, often in the form of his immature attitudes and his wacky resolution to hunt down and kill the shark that ate his friend. Cousteau himself would eventually become more environmentally conscious about his own exploits and is now regarded as a champion of marine conservation. He even created The Cousteau Society, much like The Zissou Society in "The Life Aquatic," a non-profit membership group that encourages environmental consciousness through the continued exploration and observation of underwater ecosystems. For a man like Cousteau, whose breadth of life covers much of the last century, there can be no singular summation that adequately portrays him in his fullness. But Anderson's introduction and fantastical eulogizing of Cousteau's life, revealing all his flaws and passions via Zissou's mirrored love of the ocean and the living things that lurk below it, is a pretty affecting place to start.