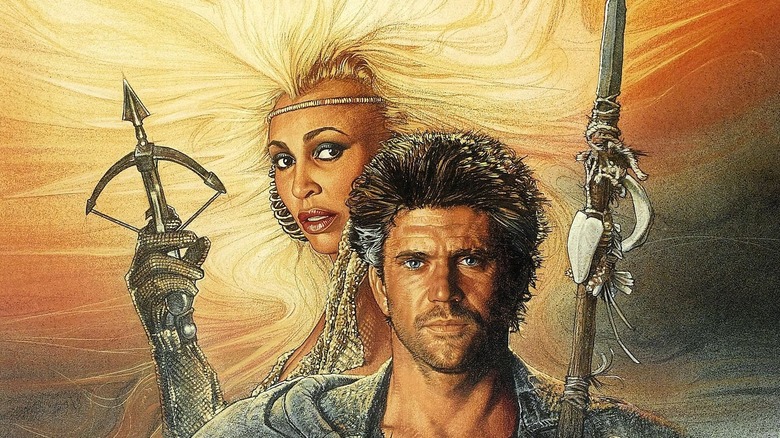

This Classic Novel Inspired Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome

George Miller's post-apocalyptic thriller "Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome" was released in 1985 to generally favorable critical acclaim and a good deal of financial success. Roger Ebert called it one of the best films of the year, citing its centerpiece fight scene — involving a dome lined with knives, bungee cords, and a lot of hooting mutants — as one of the wholly original fight scenes in cinema. In the years since its release, however, many have cited it as the black sheep of the series (which includes 1979's "Mad Max," 1981's "Mad Max 2," aka "The Road Warrior," and 2015's "Mad Max: Fury Road"). Anecdotally, I have heard critics and colleagues point to the film's second half as less exciting than the first, as the freaky and energetic fight scenes are followed by mellower scenes of Max (Mel Gibson) interacting with a tribe of children who are developing their own society — and patois — without the input of adults.

It was in this portion that audiences saw a little bit of what happened in the "Mad Max" future timeline, and how the world came to a desperate post-apocalyptic landscape full of violence and vehicle fetish. It was the first time the series became forthrightly didactic. The latter portion of "Thunderdome" has received much criticism over the years, from mere disappointment to outright outrage. Some cited said didacticism as a mere screenwriting error, preferring the series' usual anarchic sense of fun punk rock defiance. Others have merely screamed to the heavens about the how inclusion of annoying little kids interrupts the mayhem.

Those little kids, however have a clear antecedent in literature. George Miller has clearly read William Golding's 1954 novel "Lord of the Flies."

Lord of the Flies

If you're unfamiliar with "Lord of the Flies" ... well, then I suppose you were never in the fifth grade. William Golding's classic novel, frequently included on elementary school reading lists, is about a group of British schoolboys evacuating a war by plane. Their plane is shot down, and the surviving boys — all about 11 or 12 years old — have to learn to survive on a remote desert island. Over the course of the novel, readers witness the boys descend from civilization into vicious tribalism and ritual.

"Lord of the Flies" was intended to be an antidote to novels like Johann David Wyss' "The Swiss Family Robinson" (1812) or, specifically cited by Golding, R.M. Ballantyne's "The Coral Island: a Tale of the Pacific Ocean" (1857); stories that depicted being lost in the wilderness as an opportunity to rise up and be decent, creating a pastoral Arcadia of togetherness. Golding, taking a much more cynical approach, told a tale of young peoples who, free of the strictures of adult supervision, have a tendency toward savagery and power. While many young children read this book in school, I might argue that it is not for children. Like J.D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye" and William Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet," these are stories about youths that are for adults with perspective on youth. They are not necessarily for young readers.

The World from the Eyes of Children

George Miller revealed in a 1985 interview that he was interested in the perspective of the "Mad Max" universe as seen through the eyes of The Feral Kid (Emil Minty) from "Mad Max 2." The unnamed character didn't speak, and loped around like a wild animal. He even killed people with a bladed boomerang. At the film's conclusion, we learn that the Feral Kid would grow up to be the film's narrator. Miller, in a conversation he had with one of the sequel's co-screenwriters Terry Hayes, began discussing mythology, and how, perhaps if left to our own devices, humans take what little information we possess and author new meanings of how things came to be. A child with no knowledge of history — and no way of accessing written history of the past — would only have vague memories of airplanes and old worlds to draw on, and mythic figures like Max to facilitate a new pantheon of heroes.

In short, Miller pondered, what would the origin of the world look like to a child who only had "Mad Max" films to draw on? This immediately had him thinking of "Lord of the Flies," and how children are perfectly capable of creating their own myths and heroes and laws and, in the case of Golding's novel, violence. Would children let loose in the world of "Mad Max" all be Feral Kids ready to kill and to harm? Miller, perhaps more optimistic than Golding, posited that perhaps they wouldn't.

But Hopeful This Time

William Golding explored the origins of morality in his book, and how humanity's will to power can quickly devolve into a need to dominate. It's about how rational thought can be overwhelmed by base emotions. It's about the dangers of groupthink, and how groups can commit acts of violence that no individual would.

"Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome" had to be gentler and less cynical by design, mostly by dint of its hero. In the same 1985 interview, George Miller describes Mad Max as a "closet human being," in that he has humanity deep within him, but keeps it locked up in order to survive in a brutal world. It may be why the character is so appealing to several generations of fans. He's a brute who looks out for himself ... until he needs to help someone. The children in "Beyond Thunderdome" are, like the kids in "Lord of the Flies," creating their own morality as they go, but they have fallen toward myth, heroes, and togetherness. Max fills the Messiah-shaped hole in their worldview. And, in being looked up to, Max is permitted to let his humanity out. He becomes a more well-rounded human being as a result.

Violence and badassery are things to be outgrown. Perhaps fans of a badass and violent film series — who identified with Max's capacity for action — felt betrayed by a sudden injection of pacifism into the films' philosophy. Hence why "Beyond Thunderdome" still carries something of a bad reputation to this day. The adults in the "Mad Max" movies tend to be, well, mad. They are the ones obsessed with power, control of resources, and their own bloodlines. In "Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome," we learn that children are ultimately going to outgrow the darkness of the current world.

"Beyond Thunderdome," then, is just as much a rebuttal to "Lord of the Flies" as "Flies" was to "The Coral Island."