Raiders Of The Lost Ark Ending Explained: More Than A McGuffin

An homage to the adventure serials of his youth, Steven Spielberg's 1981 film "Raiders of the Lost Ark" is one of the most celebrated action adventures in motion picture history. It is also rollicking, globe-trotting fun, playfully employing the well-worn and still-reliable genre tropes from the 1930s and '40s, updated in a higher-octane action milieu. Henry "Indiana" Jones, as played by Harrison Ford, has become such a stubbornly beloved character that fans and filmmakers refuse to let him go. I suppose we are all chasing the dragon after the high of the original film.

"Raiders of the Lost Ark," while an enjoyable work of what might be described as escapism, is no mere trifle, and the religious iconography in the film is worth looking over. The titular Ark wasn't a screenwriting contrivance but based on actual Biblical lore and an important artifact among ancient Jewish tribes of the Old Testament. Let's look a bit into history.

The Book of Exodus

After the exciting action prologue of "Raiders of the Lost Ark," we are introduced to Professor Indiana Jones teaching archeology to a classroom of smitten students who are more interested in Harrison Ford's handsome visage than the ancient world. Jones is approached by two government spooks who want to employ him to track down an artifact called the Ark of the Covenant before Adolf Hitler has a chance to; "Raiders" is set in 1936, and the Nazi party had just risen to power a few years previous. Jones gives audiences a very quick exposition dump as to what the Ark is, establishing — in a screenwriting sense — its importance and its power.

The Ark of the Covenant was, looking back at the Book of Exodus, built by Moses during his 40-day sojourn on Mount Sinai, and was meant to carry the stone tablets of the original Ten Commandments. God even gave Moses blueprints: It was meant to be 2.5 cubits by 1.5 cubits by 1.5 cubits (or 4'4" by 2'7" by 2'7" in imperial measurements), covered in gold, and the two cherubim on top were meant to be spaced in such a way that a small window forms. Moses was meant to talk directly to God through that window.

During the Israelites' 40 years of wandering in the desert as described in Exodus, the Ark always went with them, a vanguard of the Tribe. It led at the crossing of the River Jordan, was carried around the city during the Battle of Jericho, and was carefully looked after by Aaron's grandson, Phinehas, where it was consulted before battles, served as an altar of lamentation, and was kept at religious centers.

The Ark traded hands many times, according to Biblical history. It was in the hands of the Philistines after it was captured in battle against the Israelites. The Philistines had a terrible time with it, as once it was in their possession, they experienced a number of plagues and curses including tumors, a mouse infestation, and the deaths of key nobles. It was placed in the temple Dagon, and the Ark seemed to divinely eff it up. People grew warts and boils. After seven months of this, the Philistines returned it to the Israelites. Smart move, I'd say.

More History!

There is a lot (like, so much) more of the Ark's history that I'll skip over, for the time being, passing briefly by King David (who intended to build a temple around the Ark) and his son, King Solomon, and going straight to King Hezekiah (731 BCE – 687 BCE), the last known Biblical owner of the Ark, and a figure from the Book of Kings (2 Kings) and the Gospel of Matthew (tipping into that new-fangled New Testament). Hezekiah is recorded as a righteous king who protected Jerusalem from the Assyrian armies by improving infrastructure in the form of protective walls, and a clever underground water channel. He also may have written the Book of Ecclesiastes, which some Biblical scholars say alludes to the Ark of the Covenant.

There were other mentions in The New Testament besides. Here's a quote from Hebrews 9:4: "The golden pot that had manna, and Aaron's rod that budded, and the tablets of the covenant." The Ark was also frequently used as a metaphor for other holy vessels, including people who carried holiness within them. In Catholic traditions, Mary, Jesus' mom, is called a vessel.

The Bible references the Ark over 200 times.

In short, the Ark of the Covenant was a powerful and powerfully sacred vessel of God, was known to carry the original Ten Commandments (as well as many other sacred relics), and had been lost to history. It was a symbol of the Jewish covenant with God, and a symbol of anything with direct contact with the Divine. Anyone who was not of the Tribe was punished for manhandling it, making it an object to be revered ... and feared.

A Tool of Revenge

Fast forward to 1981, and a Jewish filmmaker named Steven Spielberg and a Jewish screenwriter named Philip Kaufman used The Ark of the Covenant as the McGuffin in their adventure film.

But, as you may now see, it was no arbitrary choice. In terms of straight-up destructive power, The Ark may be one of the most powerful to appear in the Bible. Other Biblical holy relics may possess a comparable amount of significance (and were subsequently used in movies. See: the use of The Holy Grail in "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade"), but one was specifically designed to grant protection and destructive power to God's Chosen People.

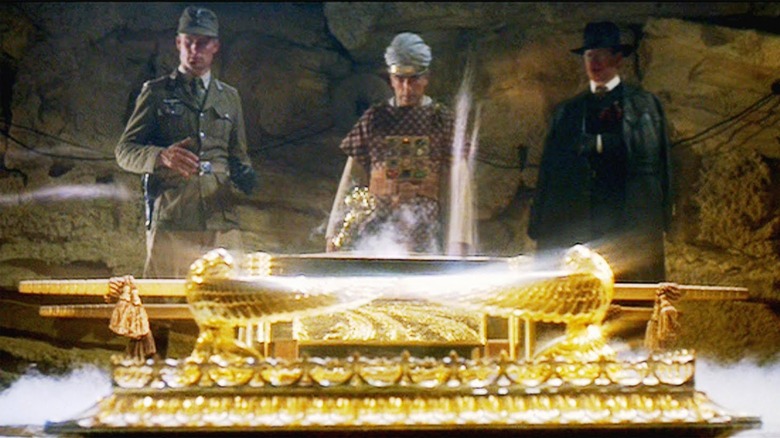

At the end of "Raiders of the Lost Ark," a group of Nazis have, well, raided the lost Ark. They have opened it up and looked inside. They touched it, wanting to steal its power. Not only are the Nazis targeting Jewish people in the streets, and were actively consigning them to concentration camps (the film is set in 1936. Dachau was built in 1933), but they are raiding Jewish heritage as well. Nothing is sacred to these monsters. Audiences in 1981 knew of all the horrors of the Holocaust, which, mind you, had ended only 36 years earlier. Philip Kaufman's parents were German Jews who fled the country. The outrage was fresh, the injustice unimaginable. It still is.

What happens, then, when Nazis stick their hands into the Ark of the Covenant? Why, they are destroyed by God's wrath. Literal angels of death make their effing heads explode. Only Indiana Jones knows that this is something too holy to witness, and keeps his eyes shut.

At the outset of "Raiders," Jones is an atheist, describing the power of the Ark as "superstitious hocus-pocus." An atheist ultimately facilitated the delivery of a Jewish artifact into the hands of the fascists it was meant to destroy. Well done, Indy.

Historical Revisionism

The Ark of the Covenant was two Jewish filmmakers using a powerful Jewish artifact to inflict cinematic revenge. "Raiders of the Lost Ark," then, is historical revisionism. It uses movie violence to achieve an act of cultural revenge. As we would see in sequels, the Nazi regime was not stopped by the events of "Raiders of the Lost Ark" — it exists in a little microcosm wherein only a group of plundering Nazis and a collaborating, amoral archeologist (Paul Freeman) were destroyed for their tampering — but it was, one might postulate, a good start.

And, perhaps abiding by the old axiom that power corrupts, the Ark (that is, the movie version) was eventually hidden away in a vast American army warehouse, nailed shut in a crate indistinguishable from the thousands of crates around it. The Ark is once again lost, this time in bureaucracy.

The "Indiana Jones" movies — with the exception of "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" — have used religious iconography heavily. "Raiders" was about a Jewish artifact destroying Nazis. "Temple of Doom" was about an artifact loosely based on the Sivalinga, the symbol of the Hindu god Shiva (an artifact that Spielberg has said was too esoteric for most film audiences). "Last Crusade" is about one of the better-known Christian artifacts, the Holy Grail.

In the world of Indiana Jones, God is combating evil, and the hard-fisted heroes of 1930s movie serials are helping along in God's plan.

The power of movies, Spielberg is arguing, is indeed divine.