C'mon C'mon Director Mike Mills On Joaquin Phoenix's Hair & His Therapist's Filmmaking Advice [Interview]

Mike Mills' movies are vivid portraits of a time and place. "Beginners," "20th Century Women," and Mills' latest film, "C'Mon C'Mon," are almost like time capsules. They're about people looking back, especially at the figures and days that defined them. "I have to do more therapy about why memory trips me out so much," Mills told us.

In "C'mon C'mon," the filmmaker tells the story of a kid (Woody Normal) and his uncle (Joaquin Phoenix) hitting the road. As the uncle tells his nephew, he'll remind him of this time if he forgets. Time is precious in Mills' work.

Recently, the writer-director told us about his fascination with memory, telling personal stories, and why he called Joaquin Phoenix's hair "El Jefe."

'I eat it up'

Your movies always bring back memories.

That's funny. The films are definitely concerned about memory. They all are, for some weird reason. I have to do more therapy about why memory trips me out so much.

The scope of this movie is probably your biggest yet, right?

What do you mean by that?

All the cities these characters go to.

Yeah. I always pitched it as it comes across as intimate, but it's really epic. It's the biggest movie I've ever done, really. I love place. I love actors, I love cinematography, and I love place. I think that's my thing I like most about directing. I love walking around alone in a city. I can remember the days I walked around Lower East Side and Chinatown with a camera, like being Robert Frank. You get to try to figure out how you could cinematically interpret this thing. I also love Wim Wenders' movies, and I feel he's always telling me, "This scene, this relationship, this emotion, this can only happen in this place, at this time." Place is that important to him, place and history. I love that.

My idea for this film, the initial impetus before I even knew the shape or what exactly it was, it's this contrast between in-the-bath level intimacy, two people in a bath together, to America, to as big as I can get. And that's how I got to this idea of all these kids in the film, all these young people in the interviews and they're traveling, like a road film in a way.

It was so fun. I eat it up. Like New Orleans, I'd love to do that again. It's so amazing to get to try to capture it. It's not unlike filming a person to me, because you're trying to make a portrait of someone and you can't show them all, but what are you going to show that reveals something interesting about them? It's the same way of how you approach a city, to me.

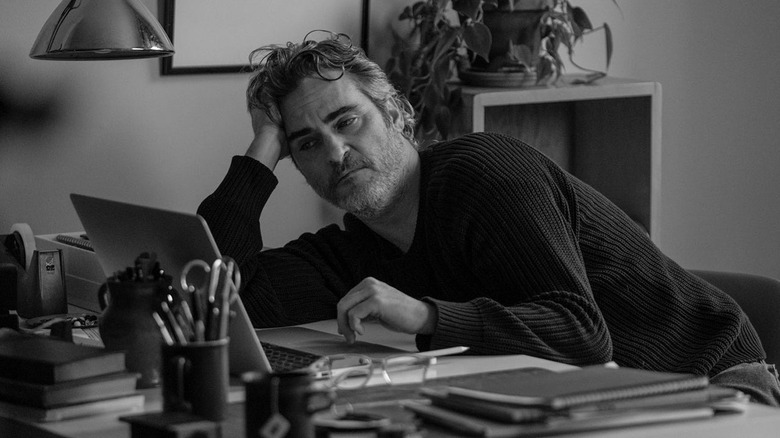

Your portrait of Joaquin Phoenix is beautiful in this movie. Even his hair.

[Laughs] I called his hair 'El Jefe' in the film. We had no hair and makeup. And so Joaquin's hair, we did a lot of haircuts to get to that haircut. It was actually a real key part of our process. Because we didn't have hair and makeup, especially at the beginning, I would just go in and do his hair before a take. He'd just come and dump his head at me and I would just move it up a little bit. So, the hair really actually is a very important part. If Joaquin was here, he'd completely agree. It's like, "Oh yeah. That's how I found it." That's the whole beginning of the whole thing.

There were six or seven haircuts to get to that haircut. It was a lot of discussion, because actors often, and I think Joaquin ... You don't want to talk about the theme. You don't want to talk about the underlying emotion that you're going to get to. You don't want to describe it. You want to talk about something safe and easy, but that helps you get there. Like, hair. That often happens. I've had that happen a lot. The haircut, the hair dye, whatever you going to do the hair, it's the door into the whole situation.

'Do you vibe?'

Who do you talk about theme with then? Your cinematographer?

No, Rob [Ryan] is very much this visual, physical person. Like, "Just give me a room, give me a problem and I'll figure it out." Okay, I'm going to contradict myself. To get Joaquin to really find his way into this film, the process was to sit around and read the script over and over again, and just think and talk. And that was before we even knew if he was going to do it. It was, if he could find a way that he really felt he could do it, right? And that went on for months. We talked about everything from our lives, our relationships with people in our lives. Children and parents, being both, to capitalism, to just everything. Joaquin was a great instigator of questions and thoughts.

Some directors say you learn more about whether an actor is right by talking about everything but the script or movie. That's true for you, too, right?

Yeah. Even if you are talking about the film and having a really interesting analytic conversation, there's this deeper underlying, energetic thing of, "Do you vibe?" It's not just vibing with you, it's like, "Oh, I'm just having a very intuitive feeling inside my chest that Annette [Bening], as I talked to her here at dinner, has some spiritual correlation with this mom character I did. It's going to get under her skin. She has her own life, her own unique history is going to fuel this." And so, that's more what I'm going for.

It's something you couldn't describe, I don't think. It's very much a in-the-chest vibe. With Joaquin and I, he nicely came to tell me, "I just don't know how I could do this. I don't know how I could do you justice. I think it's all interesting, but you know, I don't know. Who's Johnny? I don't get it." But then we just started talking and I think we just started cracking each other up and we could sort of spar with each other. And so that, more than anything, more than the script, more than anything, I think is the lifeline between the both of us.

Do a lot of great ideas come from that sparring?

Yes. Absolutely. Or just helping you understand your own material or helping you understand what you're trying to do. Just having a playmate to go through all that with.

'So anyways, my therapist, want to hear her answer?'

You make a movie about every five years. During that time, are you only working on one potential film or several?

No, I work on the one thing the whole time. I do other things to make money, but no. It's always different reasons. "Beginners" took two or three years to get financed. "20th Century Women," it took me two or three years to write that script. I had my kid right in the middle and it created all this confusion in my life and just having a kid. And this time, 2016 just knocked me off my feet. The Trump world and just what America was exposing about itself, I just didn't know how to do it. There was a year and a half maybe where I wanted to make this film, but I didn't know how to make it. I couldn't even start writing. I was just like, "Ah, I don't know how to be a filmmaker right now." So anyways, my therapist, want to hear her answer?

[Laughs] I do.

I would be really happy if I made a film every two or three years. That'd be rad. I love filmmaking and it's the best. That's just not how it's happened. And the world is fine. The world doesn't need more films. It is a little bit like capitalism talking, like, "You got to do more. You have to be more productive." It's not like I'm supplying food to hospitals with my phone. It is a luxury. It is a huge cultural privilege on my part. Also, we're all good, you know? I'm taking up enough space as it is. And this is maybe great, that it's this way.

You sound content, at least.

No, I'm not. I'm trying to talk myself into that. That's what my therapist would tell me to tell you. And me.

[Laughs] If you tell out of yourself enough times, maybe it'll come true?

Yeah. As I get older ... And then my films do come from life, so you got to spend the time to live the life, to then make the film about the life that you just lived and do that.

'That should just be a therapeutic thing everyone does'

Does writing about those life experiences ever make you look at them in a new light?

At the beginning. At the beginning is when it's its most personal, raw, real. Really about my life, really about my mom or my dad or all that. A lot of that's not sitting and writing a draft, just a notebook and just thinking of the cosmos of the film. So that part, yeah, because most of us don't spend eight hours a day thinking about your relationship with your mom. If you did, you would probably shift something or have better handles for something you already know. I think that's all. And because I was writing about my parents who were dead, it was kind of a way to commune with them or be with them because I had to be them to write them. And that's a trip. Everyone should do that. That should just be a therapeutic thing everyone does.

And then the writing gods come. The writing gods aren't under your control, and they have their own weird ideas, and I've learned to just listen to them more and more. Yeah, here are my seeds, but then they interact with the cosmos, or writing gods, or whatever the hell it is, and it takes its own weird life, like Johnny being an uncle or whatever. It's all these different things that I didn't know I was going to do at all. And then, once you meet your crew and your actors, that's the huge transformation where these ideas, and hopes, and feelings, and emotions, and problems, and all this stuff which is like raw meat, gets digested and transformed. It becomes their raw meat, and really becomes a different, very interestingly different, beast at that point.

I haven't made lunch, as you can tell.

[Laughs] Music is very important in your films, so how important is music during those early days of creating for you?

I'm not a confident writer. I just start disbelieving and get depressed and want to cancel myself. So, I had to be really caffeinated and then I listened to one song or maybe a record on repeat on headphones all day long. I just had to blast myself out of the experience. I was doing a lot of stuff with The National and I'd like a song, like "Graceless," I could listen to that song a lot. It just helps me. But then I'll shift around because I need to get into different moods or I need to help push myself. So, the song is sort of emotional psychic company.

It's like, "I'm just sort of vibing with this person, this entity called the song." Music is a deep, magical, spiritual situation, the way it functions on your neurology and your body and all that. It's the highest of the arts to me. So it's like, "I'm just being around magic." That sounds really pretentious and stupid, but it's real. That's what I believe. So, just being around magic helps you get out of rational traps and go forward.

Well, as you said, you're obsessed with time and place, and music defines both for so many people.

Yeah, yeah. To me, all the source music that's in my movies is just another way to talk about character because it's almost always someone's record collection. We're always someone playing music for someone else, which is such a part of my life. I do love that. And then The National guys ended up working on this, doing the score, and that's almost like working with an actor. Because you're sharing ideas and hopes about what it feels like. It's like a way an actor delivers a line or makes an emotion visible, those guys are making an emotional space audible.

Mr. Mills, thank you for your time.

Call me Mike. That makes me feel old, "Mr. Mills."

"C'mon C'mon" is now playing in theaters.