Every Mel Brooks Movie Ranked From Worst To Best

The laugh that turned Melvin Kaminsky into Mel Brooks was, as the filmmaker would later tell Conan O'Brien, "a giant mistake." At age 14, the stagehand and de facto understudy found himself hastily recruited to play a 70-something district attorney. In the middle of his terrified performance, Kaminsky dropped a glass of water. It shattered. His scene partner froze. The audience gasped. It was Brooks who finally walked upstage, tore his fake beard off, and pleaded, "I've never done this before!"

The director wasn't pleased, but it was too late: A star had been born (and if not a star, then at least — as Brooks himself once self-diagnosed on NPR — a "purveyor of cheap jokes"). If anyone but Mel Brooks branded themselves as such, it might sound like self-deprecation. In his case, it's how the sausage is made. "There's no way of being brighter than the audience," the director once told the New York Times. So instead of outsmarting them, he surprises, disgusts, tickles, and offends them. The show must go on, and if that means begging the front row to crack a smile, so be it. His 12 films are unmistakably his. Though it runs the gamut from iconic parody to adapted Russian literature, Mel Brooks' entire filmography owes a debt to that fake beard, and not just for the many, many fourth-wall breaks to come.

12. Robin Hood: Men in Tights

As much as "Blazing Saddles" defined Mel Brooks, it also destroyed him. Forget his first two films — he was suddenly the grand master of genre parody. On the commentary track for "Spaceballs," he still laments the detour: "I was deserting my private muse and getting into big stuff, and that may have been my mistake."

"Robin Hood: Men In Tights" might as well be a sequel to that film. It has a kitschy title song, a fantasy-adjacent princess hurtling toward a disastrously arranged marriage, and a gag-a-minute pace tailor-made for basic cable half-watches. But it also has something "Spaceballs" doesn't — flop sweat.

"Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves," itself a misbegotten nostalgia piece, provides already shaky bones. The remaining myth is boiled down to a few archery jokes. For the rest of its antsy 104 minutes, anything goes in "Men In Tights." A rapping Greek chorus? Gay panic? Arsenio whooping? A Dirty Harry impression? Nikes? All spoken for. The batting average may be low, but at least the pitching machine is making a lot of noise. It's not a wash — Cary Elwes was lab-grown to mock Errol Flynn; it's just a mess.

11. Life Stinks

Mel Brooks founded Brooksfilms as subterfuge to keep certain projects clean of his silly reputation, most famously "The Elephant Man" and "The Fly." Of the company's 19 productions, he only considered one both a Brooks film and a Brooksfilm. The difference is what sank "Life Stinks," a slapstick comedy about homelessness. Critics balked. Audiences stayed home until "Hot Shots" fatally, prophetically opened the following weekend. But time has been kind to Brooks' intent, if not always his aim.

Goddard Bolt is an American success story, a self-made billionaire on only a $5 million inheritance. When he and another developer set their sights on the same slum, they make a bet — if Bolt can survive 30 days on the street, he wins it all.

As soon as Bolt finds refuge against a kitchen door, it opens and sweeps him clean into a waiting dumpster. When he meets a mentally ill man claiming that he, too, is a disgraced tycoon, their argument devolves into a Stoogian slap fight. After the first person to show him any kindness dies unmourned on the street, Bolt watches helplessly, hopelessly, just as invisible to passersby as the corpse.

For better or worse, the whiplash is the point. Brooks respects the homeless characters enough to give them senses of humor and, in the case of Lesley Ann Warren's unapologetically jagged Molly, dreams. It briefly takes flight with a whimsical dance in a thrift store warehouse. He's got a big heart for the material, but also, perhaps, a little too much banana cream caught in his eye.

10. Dracula: Dead and Loving It

"Dead and Loving It" is a cursed thing, appropriately enough. There was no way it could've survived comparison to "Young Frankenstein," and none of the broad strokes helped. Despite the ostensible inspiration being "Bram Stoker's Dracula" in 1992, it hews dementedly close to the 1931 Universal classic. The Hammer-inspired choice to ditch black-and-white only makes its intentionally stagey sets look cheap. The final nail in the coffin was driven by the man himself: "I did 'Frankenstein, Jr.' and I said, 'I need a companion piece,'" Brooks said while working on the film.

Far removed from expectation and its own overwrought infamy, however, "Dracula: Dead and Loving It" is easy to like. The mad dash of "Men In Tights" has calmed into an amiable jog. Fewer swings, sure — but fewer misses, too. Instead of elaborate setpiece gags, Mel Brooks entrusts more punchlines to the players, coincidentally his strongest cast of ringers since "History of the World, Part I."

Nobody else could've been Mel's Dracula but Leslie Nielsen, even if it was not the comic actor's liveliest performance. Nielsen plays the Count like a man exhausted, so tired of eternity he swallows syllables whole, like all the hard sounds in "chicken." Peter MacNicol matches his every understatement with the opposite, stealing at least one scene right out from under troupe all-star Harvey Korman.

To date, "Dead and Loving It" remains the last film Mel Brooks directed (don't worry: at the ripe old age of 95, Brooks has a new one on the way). It doesn't deserve that weight or the weight of its better half, but it does deserve pleasant reappraisal.

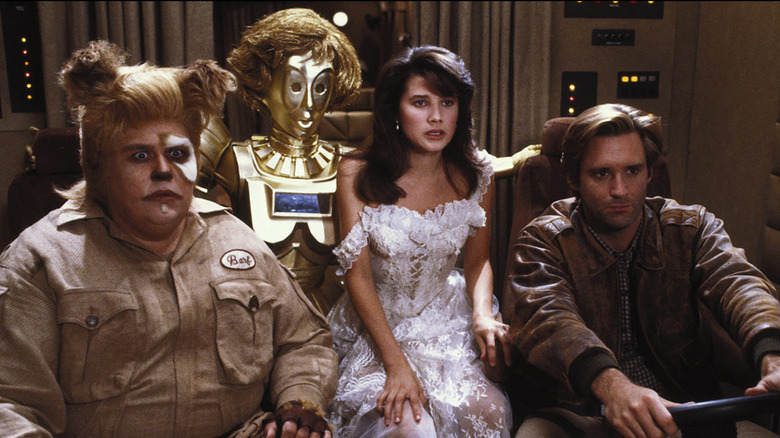

9. Spaceballs

On the electronic press kit, Mel Brooks explained his motivation as obligation: "It is the last genre I can destroy so I'm destroying it." Read between the endlessly quoted lines and it makes sense. The "genre" in question only came into existence as he was skewering the ones he grew up loving. The best bits rarely have anything to do with "Star Wars." Of all his parodies, it's easily the most perfunctory.

And yet, there are few simpler pleasures than watching Rick Moranis wear a really big helmet. The jokebook may be held together with cobwebs — Brooks' Borscht Belt Yoda is just a spry revival of his "2,000 Year Old Man" act — but the visual gags are as sharp as ever. The massive star cruiser that starts the movie and won't stop starting it. "Spaceballs": The Merchandise. Capturing the stunt doubles. Combing the desert. Killing a xenomorph and a singing frog with one stone. The finest fourth-wall break in a career founded on them. The Lucas-sized budget – Brooks' largest-ever – ended up allowing for Lucas-sized punchlines.

Six years after his last parody, four after "Return of the Jedi," and one since a plastic Han Solo hit shelves, "Spaceballs" felt and still feels like target practice. At least Brooks is one of the best shots around (and at least, as of this writing, there's been no further progress on the news of a decades-too-late sequel).

8. To Be Or Not To Be

"There's no greater joy than singing with my wife 'Sweet Georgia Brown' in Polish," said Mel Brooks (via SiriusXM Town Hall) about what he considers the most gratifying project of his career. Sentiment like that, as well as the apparent fireworks on-screen, make "To Be or Not to Be" an easy inclusion for this list despite being directed by long-time Brooks choreographer Alan Johnson.

As hammy Polish actor Frederick Bronski, Brooks sticks it to Hitler again, this time in person. When the Nazis invade, his acting troupe finds itself suddenly playing for the enemy. Occasionally, fatally, it copies the more delicate Lubitsch original line for line. Some revisions meant to bring war crimes 41 years up to date don't match its looser, louder sense of humor. The novelty rap song tie-in, however catchy, did it no favors by association.

But as the filmmaker tackling his most infamous punchline head-on, it's fascinating; Nazi jokes never cut closer to the bone. As the man falling in love with his wife all over again, it's bewitching; Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft crackle with the lived-in timing of a comedy duo and manage to fit the lopsided proportions, too. "To Be or Not to Be" is both the most complicated and personal film in the Brooks canon, and that, as well as the earnest grace between, is no coincidence.

7. The Producers

After toiling in the mines of live television on "Your Show Of Shows," Mel Brooks turned his attention toward immortality. All those episodes, all that work was recorded on the "cellophane" (as he once told Conan O'Brien's audience) to cinema's celluloid.

What better way to start than with a Hitler musical? Hollywood collectively balked at "The Producers" — Universal offered to pay for a "Springtime for Mussolini" rewrite — but Brooks stood firm. The result is just as audacious now as it was in 1968, even if its teeth have outshined its smile. Between the dancing girls wearing pretzels and proud Nazi playwrights, this is a love story between lonely frauds. Brooks would come back to that well several times, most directly in "The Twelve Chairs" and "Blazing Saddles," but never so sweetly. No image in his filmography is as pure as Gene Wilder and Zero Mostel riding the same carousel horse.

Brooks' first film granted him not only eternal life, but a long-shot Academy Award for best screenplay. Given the subject matter, it almost sounds like a scheme right out of, well...

6. History of the World, Part I

In a New York Times interview, Mel Brooks explained that the idea had come to him reflexively, when a grip from "High Anxiety" asked the filmmaker what was next. He gave him the biggest answer possible — "History of the World." The "Part 1" was only added after the grip balked at its hypothetical scope.

The resulting epic is as close as Brooks gets to Monty Python, and not just because the Spanish Inquisition arrives unexpectedly. There's no plot, just a patchwork of non-sequiturs wearing studio surplus wardrobes. It's all stitched together with velveteen narration from Orson Welles and a renewed sense of vulgarity, either harkening back to "Blazing Saddles" or thwarting the incoming class — "Stripes" would rake in nearly three times as much on the same budget.

But what the competition lacked was showbiz shamelessness. "The meek will never inherit the earth," decided Brooks, distilling the annals of man down to the same old groaners translated across eons to make the same old miseries tolerable. Hair-breadth escapes are made with enormous blunts. An impostor is revealed by an ill-timed erection. Entire cultures run on pee jokes. Works every time (and has, for a very long time).

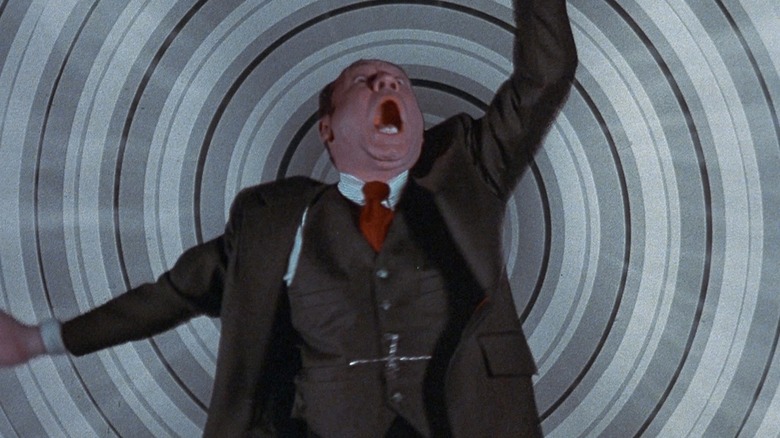

5. High Anxiety

Alfred Hitchcock's final film, "The Family Plot," was released a year before "High Anxiety." Given that Hitch was still a decade away from posthumous canonization, it was an odd time to give him a noogie. The only reason Mel Brooks could or would have done it, he once told NPR, was love: "Alfred Hitchcock was the very best director who ever directed films."

Accordingly, and sometimes to a fault, "High Anxiety" is his most disciplined parody. He takes the cinematic subtext of Hitchcock ("camera as deadly weapon") and makes it self-aware text: At one point, the lens breaks a window after dollying too far. The parody doesn't stretch much farther than Brooks' wrong-place-wrong-time hero getting pelted with bird poop, though in that scene's defense, it was Hitch's idea. To those well versed in the Master of Suspense, it's an exhaustive love letter. To everyone else, it works just fine as an exceptionally silly thriller.

As a too-soon satire, "High Anxiety" has only appreciated in value. Riffs that played primarily to cinephiles don't need as much translation today and, if they do, the entire Hitchcock canon is just a few clicks away. Then again, anyone can appreciate The Psycho-Neurotic Institute for the Very, Very Nervous. It's not Brooks' funniest parody, but it is his nerdiest and, like the crooned title number, still very hard to resist.

4. The Twelve Chairs

"The Twelve Chairs" feels like a vestigial limb. Despite releasing a mere year after "The Producers" earned its Oscar, Mel Brooks' follow-up (as he once told Consequence of Sound) "never crossed the George Washington Bridge," sticking around only in major markets and not for very long. It's not a parody, as would soon become his stock-in-trade. There's no obvious debt to the theater. It is, instead, a shopworn Russian fable presented with surprising conviction and only the gentlest Brooksian touch.

The only thing disgraced aristocrat Vorobyaninov, suave conman Bender, and ethically-compromised Father Fyodor have in common is greed. But that's bond enough to send them scrambling across Russia in search of 12 chairs, one of which contains a family fortune hidden away from the Communists. Along the way, they lie, cheat, steal, and draw crooked lines in the sand about which sins are still beneath them. It's high adventure for lowlifes — a later chair is intercepted mid-highwire act — but shot through with tender sympathy for such broken souls.

If there is a Brooks-brand philosophy, it's summarized in his title song: "Hope for the best, expect the worst." The crooks are all closer to beggars than billionaires but they're too busy counting money they don't yet have to notice. If and when the check comes, what else is there to do but laugh? It's as close as Brooks gets to a dissertation on faith, best summarized in a single line from Dom DeLuise's greedy Father Fyodor, who received enough divine strength to climb a mountain, but not enough to climb back down: "Oh Lord, you're so strict."

3. Silent Movie

After the one-two punch of "Blazing Saddles" and "Young Frankenstein," Mel Brooks could do just about anything he wanted. Naturally, he made the first silent film in over 40 years and made it about the making of the first silent film in over 40 years.

20th Century Fox was so nervous they insisted he record dialogue just in case; Brooks didn't even rent a microphone. "Silent Movie" is fearlessly old-fashioned. Contemporary technology bends to the ancient will of slapstick; Dom DeLuise and Marty Feldman's monkeying with an EKG monitor devolves into a game of Pong for Sid Caesar's life. Star-studded cameos, the only reason Brooks' stand-in is allowed to make a silent film, weren't even included on American posters. This is anarchy from tip to tail, from Burt Reynolds's shower to the Coke Machine mortar fire.

Brooks, in his first starring role, commits with the madcap glee of a man who knows exactly what he's getting away with. He skewered the studios! He scored Hollywood's hottest stars for (an alleged) $138 a day! He made a mime speak! No wonder "Silent Movie" is not only his quietest motion picture, but also his giddiest.

2. Blazing Saddles

The dirty little secret of the Couldn't-Make-That-Today brigade is that "Blazing Saddles" also couldn't have been made in 1974. And yet, against all odds and taste, it was — a miracle from the very beginning.

"'Blazing Saddles' was more or less written in the middle of a drunken fistfight," recalls Mel Brooks (via Creative Screenwriting). Horses are punched. Randolph Scott is revered. Baked beans do what baked beans do. It's a live-action Looney Tune so ruthless that it makes and lands a punchline out of the actual Looney Tunes theme. Cleavon Little, missing only a cartoon carrot, is the Platonic ideal of Brooksian leading men, running easy rings around the dim and bigoted frontier. It's a performance made all the more impressive by the fact he's also the first Brooksian leading man.

What's often lost in the alternately reactionary and revelatory nostalgia around "Blazing Saddles" is that it's the Mel Brooks parody primordial. Within seven years, he'd have five to his name, but every last instinct was laid down here as sacred text, potent as it would ever be. The golden rule is simple and absolute: Only the laughs matter. He never scored so many, so fast or so furiously, again.

"I make the things nobody else would make," Brooks recently explained to CBS News, in something like a proud apology. Thank goodness.

1. Young Frankenstein

The difference between "Blazing Saddles" and "Young Frankenstein," released just 10 months apart, is the difference between a shotgun and a scalpel. In lieu of the earlier film's writing posse, "Frankenstein" started and stopped with Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks. In a 1975 Cincinnati Enquirer interview, the former recalled the latter laying out their partnership plainly: "Your job is to make me less broad. My job is to make you less subtle." Their matrimony would be one of the holiest in comedy history.

But laughs weren't the be-all, end-all to Brooks: "I didn't want it to be just funny or silly," he told the L.A. Times. In devotion to the Universal classics, he minted a functional, if significantly funnier summary of and sequel to them. It's a Frankenstein story with all the hubris, plus a tap number set to "Puttin' on the Ritz." Every bit works and, just as impressively, breathes. The rhythm allows for moments of genuine suspense and tragedy, however fleeting. The regulars — Wilder, Marty Feldman, Cloris Leachman, Kenneth Mars, Madeline Kahn — outshine the rest of their collaborations.

What truly, definitively sets "Young Frankenstein" apart from other Brooks films, especially his parodies, is how fragile it all is. Wilder refused to let the director play Igor out of concern for that precarious balance: "I want it to be a real movie with natural comedy," as he described to Parade in 2013. Brooks understood. To their collective credit, that's exactly what it is, from start to schwanzstucker (its next iteration, which has yet to surface, will presumably be much different).

Whether or not it's a better film than "Blazing Saddles" will remain in question so long as man keeps numbering things. The truth is much simpler. It's tomato, toe-mah-to. Frankenstein, Fronk-ensteen.