15 Must-Watch Documentaries About Filmmaking

On its best day, filmmaking is alchemy. On the rest, it's an affront to the natural order. Forming something from nothing in any other medium is a fundamentally lonely pursuit. Movies, by contrast, are deceit as a team sport. Armies, anywhere from a handful to hundreds strong, must march in microscopic lockstep — no matter the scope, scale, or genre, all films are made one shot at a time.

It's a miracle that Frank Capra considered a disease. "When it infects your bloodstream, it takes over as the number one hormone," he said. Those afflicted can't help themselves and wouldn't have it any other way. That makes for a fine line between passion and delusion, finer than any one documentary could possibly illuminate. The following 15 chart the agony and ecstasy of filmmaking, in macro and miniature, across many of its component processes. Spiraling budgets. Backyard sets. Shot on camcorders or CinemaScope. It's all the same madness on-screen.

Overnight

"Overnight" used to be a cautionary tale. Director Troy Duffy pulled the brass ring of all brass rings — a $300,000 paycheck for his first script, a $15 million budget to direct it, a recording contract for his band, and the guidance of the powerbroker that personally mentored Quentin Tarantino. All the circumstances that made his meteoric rise possible are extinct or incarcerated. It might as well be a "Twilight Zone" episode now.

But despite the devil involved, there is no catch. Duffy's implosion is a staggeringly fast series of unforced errors. He ridicules every actor interested — Brad Pitt, Keanu Reeves, Kenneth Branagh — based on, at best, a meeting's worth of interaction. "Success has nothing to do with how you live your life and how you treat your friends," he says amidst B-roll footage of dwindling allies watching their shared success circle the drain.

The off-camera punchline is that he sets it all on fire to make "The Boondock Saints." Once upon a time, "Overnight" was a car crash for indie dreamers to gawk at on their way to work. Now, it's a cannon act with no net, even more fantastic, and even more violent.

Kid Icarus

"I don't want to be branded as the next Spielberg," admits 18-year-old film student Leigh Harkrider, "I want to be branded as the new Harkrider." It's the first point in a pattern. Harkrider credits filmmakers for his passion, but rarely films. He is, like so many listless film students before him, doomed before the word "Action."

Mike Ott, documentarian and community college professor of Harkrider, gives the fledgling director all the rope he needs to hang his career-making debut, "Enslavence." During the script meetings, Harkrider overrules his ghost-screenwriter to keep both sexual assault and drug addiction in the picture. Instead of asking for help, he invites cast and crew to "share this experience." Every mistake that can be made, every cliché that can be indulged is.

Ott lets the youthful megalomania self-destruct and zooms in on the beating, broken heart left in the ruins. "Kid Icarus" ultimately asks a simple question that too many wannabe filmmakers blow right past – Why do you want to do this, exactly?

American Movie

The human condition is captured between credits at a desk top-heavy with unopened bills. Aspiring filmmaker Mark Borchardt slits them one at a time and bemoans each fee like losing lottery numbers. In the last envelope, however, he finds a new Mastercard. "I don't believe it, man," he beams. "Life is kind of cool sometimes."

So it goes for Borchardt, though it doesn't take a Menomonee Falls mailing address to empathize. He lives shift to shift as a graveyard night janitor. What he doesn't accidentally blow on peppermint schnapps and long-distance calls to Morocco he sends to his three kids. Waking hours are spent with unfailingly supportive family and the usual local suspects, like amiably spacey best bud Mike Schank. But somehow, some way, he will complete his passion project, "Northwestern."

The method he settles on is shooting and selling another movie entirely. Production happens between delinquency notices, Burger King runs, and late-night loiters at the grocery store. It's the American Dream as a hang-out picture that just so happens to be non-fiction, enough to make anyone want to grab their friends and film something, credit cards be damned.

Shirkers

"Shirkers" is about an unforgivable sin. In the early '90s, when Singapore had the highest rate of movie-goers in the world, teenager Sandi Tan and her friends dreamed only of making their own. As soon as they did, their mentor-turned-director stole the footage and disappeared, turning their hopes, bonds, and careers into scarred hypotheticals.

"Shirkers" is Schrödinger's making-of. Surviving reels of the film tantalize as mirage. Missing a soundtrack, it is permanently imperfect, just like Tan's memories of production. But in reworking what's left, along with her notes and drawings, Tan reclaims the film for the women that put their childhoods into it, at long last.

Although the thief looms large over the investigation, he's not worth as much as the smoking crater he left behind. Without him, who knows where Tan and company's collective passion could've taken them. "Shirkers" is an irresistible reckoning, the shrapnel of What Could've Been mosaicked into What Can Be, both for Tan and any aspiring onlookers.

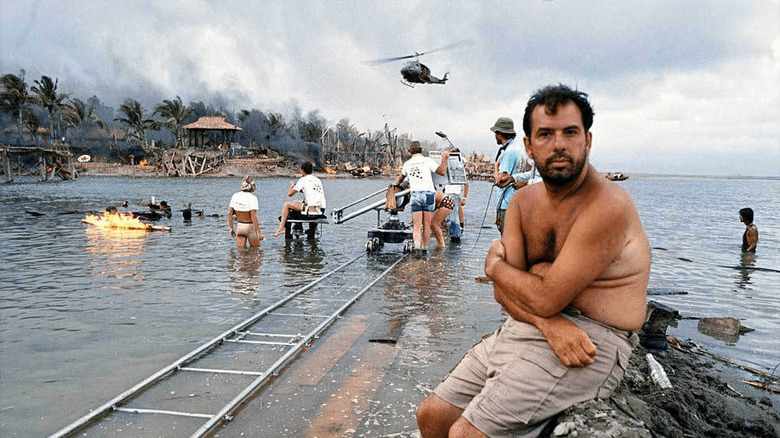

Hearts of Darkness

Filmmaking is a confidence game. Decisions made are compounding wagers against the self, with wins or losses months, if not years, away. "Hearts of Darkness" takes Francis Ford Coppola, an unstoppable force fresh from "The Godfather Part II," and crashes him into an endless series of immovable objects until even his basest instincts are shot: "I tell you from the bottom of my heart that I am making a bad film."

Knowing "Apocalypse Now" is one of the greatest films ever made stains each doubt fatal; the crew worry about finishing a movie, but have no idea how narrowly they finish the movie. Typhoons flatten the sets. Marlon Brando falters on the schedule, then the script. Harvey Keitel is fired a few weeks into production and Martin Sheen, his replacement, suffers a severe heart attack not long after. 14 weeks of rolling cameras turn into, give or take, an entire year. The meter's always running and always on Coppola's dime.

In the midst of a historic disaster, Coppola asks the unaskable question that every filmmaker knows by heart: "Why can't I just have the courage to say, 'It's no good'?"

Corman's World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel

On the first official Roger Corman production, "Monster From The Ocean Floor," he personally transported and unloaded the camera equipment each day because he couldn't afford to pay the crew another hour. At the intersection of art and commerce, Corman is probably shooting a direct-to-video movie about a mutant snake for a buck-twenty-five.

"They weren't encumbered by having to deal with art," says Martin Scorsese with apparent warmth. He should know — the "King of the Bs" gave him his first shot. In producing movies his way, on his take-no-prisoners bottom line, Corman founded a low-rent conservatory for budding filmmakers. Star pupils include Peter Bogdanovich, Jack Nicholson, Jonathan Demme, Joe Dante, Robert De Niro, and Ron Howard. They delivered and he kept his promise: "If you do a good job on this film, you'll never have to work for me again."

There will never be another pioneer like him — blockbusters stole his act and the establishment wouldn't even let him out of the rain — but this is tribute enough. Just try watching Nicholson fight tears and not do the same.

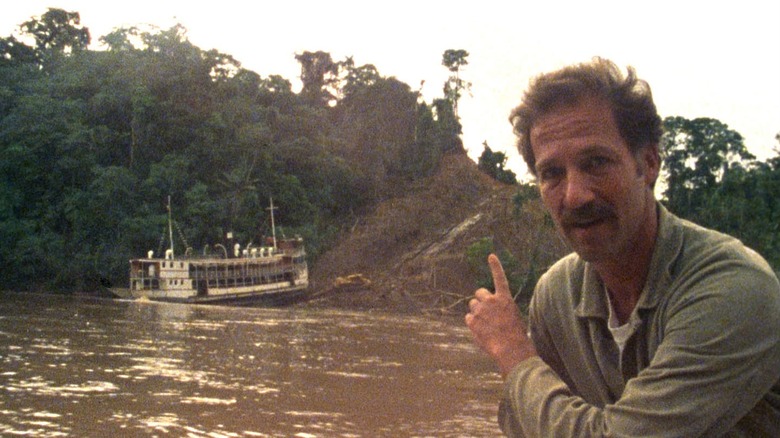

Burden of Dreams

"If I abandon this project, I will be a man without dreams," says Werner Herzog, hiding behind a primal thicket of beard. This is not a documentary about the unmaking of a major motion picture, though the regular disasters are presented without varnish. "Burden of Dreams" is an unblinking stare at the inherent mania of filmmaking. Herzog knows that he's challenging all possible gods with the act of creation, but without daring to do it, he's less than human.

"Fitzcarraldo" is about a real-life dreamer, a rubber baron determined to haul an entire steamship over a mountain. The actual man did it piece by piece. His fictional counterpart, as written and directed by Herzog, saw no need for deconstruction. The agonizing drag transcends metaphor — Herzog's impossible boat is Fitzcarraldo's and his, Herzog's. Why is he hellbent on beating the odds, in an environment he hates that he suspects hates him back?

Documentarian Les Blank doesn't offer any easy answers or apologies for his subject, but by the end, he finds something like understanding. It's as close as any documentary gets to defining the indefinable compulsion that keeps filmmakers making.

Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner

Hampton Fancher, the originating screenwriter on what would become "Blade Runner," wanted Robert Mitchum for the leading man. Producers countered with a list: Dustin Hoffman, Peter Falk, Al Pacino, Nick Nolte, Burt Reynolds. IMDb is lousy with similar factoids. What sets "Dangerous Days" apart is the sweat in-between — Hoffman met with the filmmakers for months and even appeared in concept art, but the production moved on when he insisted on giving the film a message.

At three-and-a-half hours long, "Dangerous Days" is a lot of sweat. Most decisions, from script to set to special edition salvage, get their due, turning the doc into an exhaustive checklist on how to make the definitive cinematic vision of the future. The working title is explained. The working working title is explained. There's a comprehensive featurette on miniature construction and photography hidden in the second hour.

Mileage may vary given your personal attachment to "Blade Runner," but its ambition does make for a broad education on the filmmaking process. Does that throwaway shot of a passing blimp seem easy? Maybe it is, maybe it isn't, but it looks like absolutely nothing else. Just like tears, sweat gets lost in rain.

Side by Side

When Keanu Reeves asks David Lynch if he's done shooting on celluloid, the filmmaker weighs it like a life sentence: "Don't hold me to it, Keanu, but I think I am." Such is the appeal of "Side By Side," an eavesdropped montage of directors and cinematographers passionately disagreeing with each other about the most fundamental process of filmmaking.

For his pioneering work in digital cinematography, George Lucas is referred to alternately as an egalitarian messiah and a reckless philistine. Take it as the rule: Battle lines are drawn sharp and wide, with little dynamic range between them. "I'm not going to trade my oil paints for a set of crayons," says Wally Pfister, Christopher Nolan's long-time DP. Early adopters like Steven Soderbergh, David Fincher, and James Cameron are never turning back. Computers will improve, but film can't. Digital means democratization, but more noise. And what of all the jobs that can't, won't, and haven't made the leap between?

The war still rages. The celluloid faction has lost considerable ground. The doc doesn't crown a winner, but that's the beauty of it — film or digital, "Side By Side" drags everyone into the fight.

Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound

Veteran sound editor Midge Costin took her experience on films like "Days of Thunder" and "Armageddon" and turned it into a one-stop shop. Across 95 minutes, she provides both an A-to-B of the form and a step-by-step process of how it's done. "Your job," says composer Hans Zimmer, "is to come up with the unimaginable." What's shocking is how recently, in the grand scheme of cinema, the unimaginable became possible.

The sonic gold rush started in earnest when sound montage editor Walter Murch and Francis Ford Coppola realized that leaner, meaner recording equipment untethered them from the Hollywood system. It was microphones, not cameras, that gave filmmakers freedom. Murch would go on to become the first-ever credited sound designer, forming a holy trinity alongside Ben Burtt and Gary Rydstrom as the noisemakers of modern pop culture.

Costin taps deep into that joy of discovery. The field work that led to a smacked wire becoming the once and future sound of lasers. The delicately woven cacophony that made Robert Altman movies Robert Altman movies. Barbra Streisand risking "Funny Girl" to sing instead of lip-sync. It's just as adventurous as the rest of the process, and "Making Waves" proudly proves it.

The Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing

Steven Spielberg fought Verna Fields in the editing room — also her pool house — over that darn shark. Every successful take cost him years of his life; the director wanted to see more of it. The editor, affectionately known as "Mother Cutter," wouldn't let him. Spielberg might've made "Jaws," but Fields made "Jaws" terrifying.

"The Cutting Edge" is both history and practicum. There are plenty of high-wattage anecdotes, like James Cameron learning the power of frames after disastrously removing one every second from "Terminator 2: Judgment Day," but the theory is the thing. Legendary editor Walter Murch defines his role as "the ombudsman for the audience," a band apart for their behalf. The Russian school of Kuleshov contradiction is celebrated alongside the softer emotional rules of the French New Wave. The only absolute is touch — every cut needs an artist holding the scissors.

Documentarian Wendy Apple sheds vital light on film's most invaluable, most invisible process. Editors spin straw into gold, even though their only reward might be Steven Seagal "playfully" demonstrating choke-out moves on them because they won't cut his fights the way he wants.

The Definitive Document of the Dead

In its original 66-minute form, "Document of the Dead" was an accidental novelty, an overlong educational film about making movies that just so happened to cover one of the greatest horror films ever made. Expanded to 102 minutes with updates from the sets of "Two Evil Eyes" and "Diary of the Dead," it's a complete Master of Horror life cycle.

George Romero never got small, only the pictures did. "Dawn of the Dead" offered him about as much freedom as he'd ever taste. "Having that extra weight is a trip," he says, wandering the empty shopping mall like a peasant suddenly in charge of a kingdom. By the end of "Document," he's gritting his teeth on the con circuit and telling too much truth, "Trying to find an easier way to make a buck."

The "Definitive" cut is pure Frankenstein, with the shambling gait to match. There's altogether too much fan material. The director inserts himself a little more with each time warp to disastrous, accidentally revealing effect. But Romero's no-nonsense philosophy is bulletproof, even if it ultimately made him and Hollywood strange bedfellows.

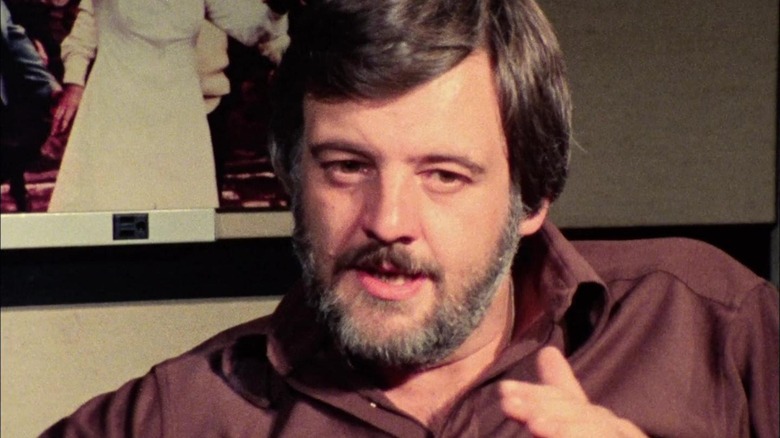

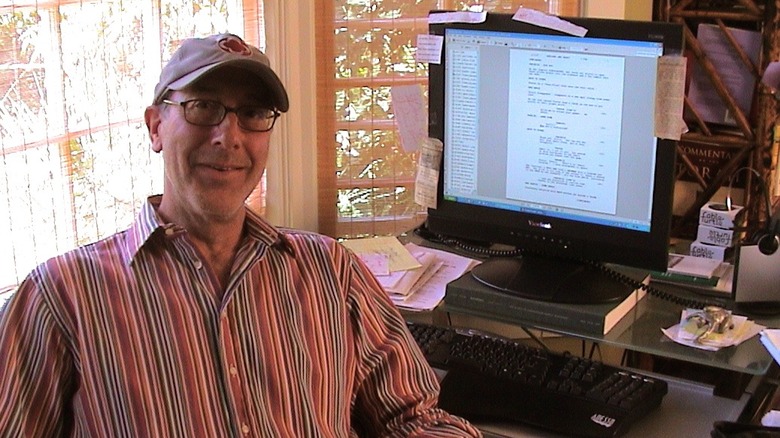

Tales from the Script

There's something perversely appropriate about a screenwriting documentary looking like a DVD extra buried three menus deep. With the exception of relevant film clips and B-roll footage trying to make the writing process look cinematic, it's wall-to-wall talking heads. The endless conversation is a feature, not a bug; nobody ever listens to screenwriters off the page.

"Tales from the Script" is equal parts frustrated tell-all and Scared Straight program. Viewers expecting a warm or poetic reflection on the form need not apply. This is about the Business with a capital-B. In the tough love words of "2010" director Peter Hyams: "If you're not prepared to do a lot of push-ups, don't enlist in the Marines."

There are few miracles here. There are only one or two accounts of the right script finding the right desk within the first hundred tries. The only thing more random than failure is success, something "Last Action Hero" scribe Zak Penn compares to "winning the lottery for something you actually did." Perspectives range from one-time wunderkinds to battle-hardened veterans. Acclimate to the despair in the air and there's a lesson for every screenwriter. The simplest comes from John Carpenter, the biggest pragmatist in any room: "Learn to love it."

Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films

"Movies are an unreal environment at the best of times," says "Death Wish III" gang member Alex Winter, "and the Cannon movies were like that times a hundred."

The Cannon Film Group model, as masterminded by Israeli film moguls Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, worked like this: paint a schlocky poster, attach a star who may or may not know they're attached, take it to Cannes, sell the rights to foreign markets, use the funds to actually make the movie. The vicious cycle meant only the most predictably lurid projects got funded (see: "Death Wish II," "III," "4: The Crackdown," and "V: The Face of Death").

Golan and Globus spent the 1980s chasing the zeitgeist at cut-race prices, only inflecting it by accident. In the hands of exploitation specialist Mark Hartley, the Cannon odyssey feels like being pleasantly stuck inside a pinball machine. But a warning about life in B-pictures lurks between chyrons. Unpaid crews. Gunpoint nudity. Sadistic directors. The most damning accusation of all comes during the end credits — somewhere along the line, Cannon's Bs became Hollywood's As.

King Cohen

There are independent filmmakers, and then there's Larry Cohen.

"Larry Cohen is so much the invisible man in relation to mainstream Hollywood," diagnoses screenwriter and critic F.X. Feeney. From his earliest days toiling in the mines of live television, Cohen was a conceptual prophet. "The Invaders" foretold "The X-Files." "Coronet Blue" foretold Bourne. A spec script he wrote for "The Naked City" in 1961 was eventually sold to "NYPD Blue" in 1995. What makes him, and the doc, essential is his spirit.

Herzog gets all the credit for encouraging filmmakers to break the law, but it was Cohen who staged a shooting in the middle of a New York City police parade without warning and convinced Andy Kaufman to pull the trigger. No obstacle or threat of self-preservation ever got in his way. And what if somebody stops him? "Who cares? What do they know?"

With its stolen airport fistfights and printed apologies for raining shell casings off the Chrysler Building, "King Cohen" is an anarchist's cookbook read by the man who wrote it, still proud of his recipes all these years later.