25 Movies Like Fight Club That Are Definitely Worth Watching

There's probably some internet law that states that any article about "Fight Club" must include some reference to or spoof the infamous "The first rule of Fight Club is" quote, but — like many of the films in this list — I'm going to break with tradition.

Arriving hot on the heels of the Baby Boomers were Generation X, and with them came a number of traits common to a great many films on this (far from exhaustive) list: a world-weariness, and a tendency towards nihilism and anti-authoritarianism. If you enjoyed the superlative "Fight Club," an entire generation of filmmakers and actors would like to let you know that there's a lot more like it — from smart, psychological thrillers, to thought provoking blacker-than-black comedies — or, if it's what you're craving, the occasional movie with a jaw-dropping twist at the end.

The Game (1997)

"The Game," David Fincher's 1997 predecessor to "Fight Club," stars Michael Douglas as Nicholas Van Orton, a work and wealth-obsessed banker. His brother Conrad (Sean Penn) returns into his life to present him with an unusual birthday gift. What do you get the man who has everything? If you're Conrad, you enroll him into a ridiculously convoluted conspiracy — one where he will struggle to determine what is part of the game and what is not, and one which will see him penniless and scared for his very life. (Truth be told, he would probably rather have had some nice aftershave. Even socks would have been preferable to finding yourself buried alive in a Mexican cemetery.)

It's a film where mere suspension of disbelief isn't sufficient — you'll need to get that sucker sub-orbital — but is a brilliantly shot and multi-layered experience. The plot-holes are thinly papered over, but the film moves as such a frenetic pace that you simply won't have time to worry about them. Fincher once again proves himself the auteur and expert in the smart and thought-provoking thriller.

The Platform (2019)

Goreng wakes in a cell on level 48 of a vertical underground jail. He learns of a platform that begins on the penthouse floor fully laden with the finest of foods, and that slowly descends through the floors of the prison. Those on the top floor eat well, but the further down in the structure, the more the inmates must fight to survive over the scraps that they are left — and nobody who wants to retain their sanity dares to think about the poor souls on the very bottom floors.

As a social satire, it's difficult to find a more heavy-handed one than this 2019 Spanish science-fiction thriller — nuance is thrown out of the window for this none-too subtle metaphor of society and our role within it. The setting is reminiscent of that in 1997's "Cube," another movie set in an individual location to significant effect, but as a satire it's particularly on the nose.

It's a film with genuine surprises and is not for one of the squeamish. That said, the gore and violence never feels gratuitous — just a logical representation of what life would be like in such a hellhole.

Jacob's Ladder (1990)

Vietnam veteran Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins) is fighting a losing battle against mental illness, fighting violent flashbacks and terrifying hallucinations. His life falls apart as he struggles to recognize fiction from reality, eventually learning of an inhumane experiment that may have been conducted on Jacob and his platoon during the war.

Adrian Lyne's 1990 psychological horror film is notable for both a standout performance from Tim Robbins as the tortured Jacob, as well as a sympathetic portrayal of what we now refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder. Jacob's visions are at times subtle, and at other times absolute nightmare fuel. The Jacob's Ladder of the title (as well as being a none-too delicate link to the name Robbins' lead) refers to the Biblical spiritual bridge between Heaven and Earth, which is appropriate for his mental state — the character is effectively stuck in purgatory, unable to move on due to his personal demons.

There's a powerful twist at the end, which works for some but not others. It's an interesting rug pull, prompting repeat viewings of the movie and elegantly reworking the meanings and motivations of the scenes and supporting characters. It was remade in 2019 to little fanfare or applause.

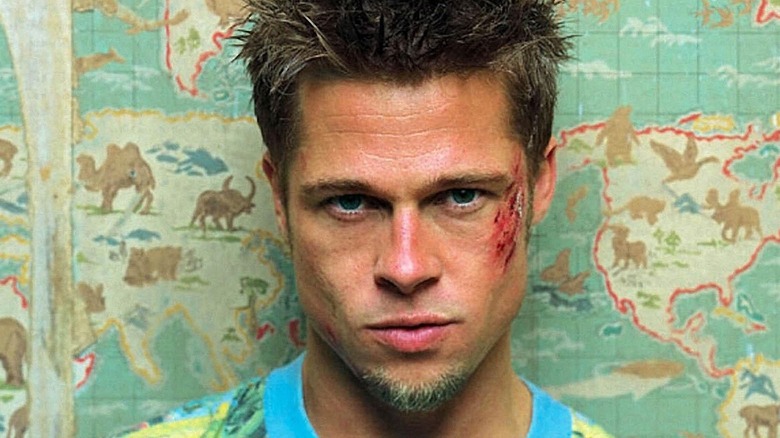

The Matrix (1999)

It's easy to forget more than two decades later that "The Matrix" was more than just a showcase for some revolutionary bullet-time effects and making leather trench-coats the most popular they'd been since World War II. For an action film, it throws out some genuinely subversive concepts.

For better or worse, it gave us the term "Red Pill" which has fallen into common use as internet shorthand to try to abruptly halt reasonable discourse, and — on a more positive note — co-writer/director Lilly Wachowski has stated that Neo's discovery of self and subsequent empowerment from his fake existence is a parallel for her own experience as a trans woman. Science fiction is no stranger to high concept ideas; "Brazil" gives us the ludicrousness of bureaucracy, "Arrival" shows us rebirth through grief, and "Aliens" presents a Vietnam War parallel. "The Matrix" packages its high concepts particularly elegantly, giving us memorable set pieces and guns — lots of guns.

Office Space (1999)

If "Fight Club" can be viewed as a pitch-black satire about anti-capitalism, "Office Space" performs a slightly less harsh — but no less effective — critique on the mechanisms of capitalism and the worker-drone drudgery of the nine-to-five employee. Both movies go to show the results of breaking or ignoring the rules.

Office worker Peter Gibbons undergoes hypnotherapy to help his mental state, but his therapist dies mid-session. Left in a permanent tranquil state, Peter — through his new-found peace of mind and refusal to conform — finds himself accidentally fast-tracked to management. Realizing that the entire system is effectively broken, Peter and his friends seek to swindle his employer by means of revenge.

It's hilarious and well-observed, but the sort of the film that'll make any office worker cringe hard enough to turn themselves inside out. Mike Judge would later go on to direct the equally biting "Idiocracy," a preposterously far-fetched movie of a populace obsessed with dumbed-down gameshows and reality TV being ruled by an ill-equipped man-child of a President.

Grosse Point Blank (1997)

If it's cynicism you're after, they don't come much more sardonic than Martin Q. Blank, the jaded assassin and protagonist of "Grosse Point Blank" who once killed the president of Paraguay with a fork.

Needing to gather his thoughts after a failed assignment, he reluctantly follows the advice of his equally reluctant psychologist and undertakes the most feared assignment of all — to travel back to his hometown of Grosse Point, Michigan, and attend his ten-year high school reunion.

There's rich comedy potential to exploit from the premise the high school reunion, of the Prodigal son returning home — after all, who amongst us wouldn't love to gloat about our success to our former classmates? Cusack again plays the type of character he fits like a glove: Blank is witty, likeable, dry, and charming. For a film about a killer-for-hire, it's surprisingly poignant and relatable — all about legacy and what we can expect to leave behind when we've gone. Also worthy of note is Dan Ackroyd cast against type as a rival hitman trying (unsuccessfully) to form an assassin's union.

V for Vendetta (2006)

Based on the Alan Moore and David Lloyd comic series from the early '80s, the film is set in an alternative reality: a pandemic is devastating Europe, America is in the midst of a bloody second civil war, and British is a far-right totalitarian and oppressive regime with zero tolerance for what it deems "undesirables." A Guy Fawkes mask-clad vigilante known only as V fights a lone war against the authorities, and his paths cross with our protagonist — Evey, a television studio worker.

Freedom through anarchy is the message here, a theme also redolent of "Fight Club" — although the larger motif at work here is the power of symbolism, and of the power of the people. Of course, the V Guy Fawkes mask — in fact, the particular design from the comic and the movie — has become iconic in the real world also, adopted by both Anonymous hacktivists and the Occupy movement. That such a symbol is used to denote hidden commitment to a shared cause yet ultimately profits a film company is not without a certain irony that even V himself might find amusing.

The Usual Suspects (1995)

Roger "Verbal" Kint (Kevin Spacey), small-time crook, is being interrogated by the police for his role in a heist. His tale is told through narration and flashbacks, as we follow the circumstances that saw Roger and his ill-fated criminal compatriots drawn under the control of a mysterious crime lord known only as Keyser Söze.

A personal aside: The feature writer is, at times, faced with an interesting conundrum. I'm trying to convince you to watch a film based on the twist in another film, and I can't guarantee that you've seen either. And if I've encouraged you to watch either, is it fair to spoil a film that's at least two decades old and ruin your subsequent enjoyment?

So, I'll just leave it at this. If you're fond of the twist in "Fight Club" where it turns out that ████████ turned out to be ████████ and that ████████ was a ███████ of his ████████, then you'll love the bit in "Usual Suspects" where it turns out that ████████ was ████████ all along. Enjoy.

Burn After Reading (2008)

When Linda and Chad (Frances McDormand and Brad Pitt, respectively) find a disk belonging to a former CIA analyst in the gym where they work, they see it as an opportunity to make money — believing the contents are classified information, and not just the mundane memoirs they actually are. One event leads to another, various spy agencies get involved with varying degrees of success, and everything goes horribly, catastrophically wrong.

In their star-studded 2008 dark comedy, the Coen Brothers once again steadfastly refuse to be pigeonholed. What on the surface seems to be a straightforward farce in the classic tradition, ends up becoming something far darker and hopelessly nihilistic. Despite the reassurances of our government bodies, the people that populate them are on the whole stupid, inept, greedy, or careless and it's a miracle that anything operates with any semblance of reliability at all. As "Burn Without Reading" shows, we're all at the whim of entropy and chaos. And, unsurprisingly in this era of supposed "fake news," things have barely changed since the movie's release. Or more accurately, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

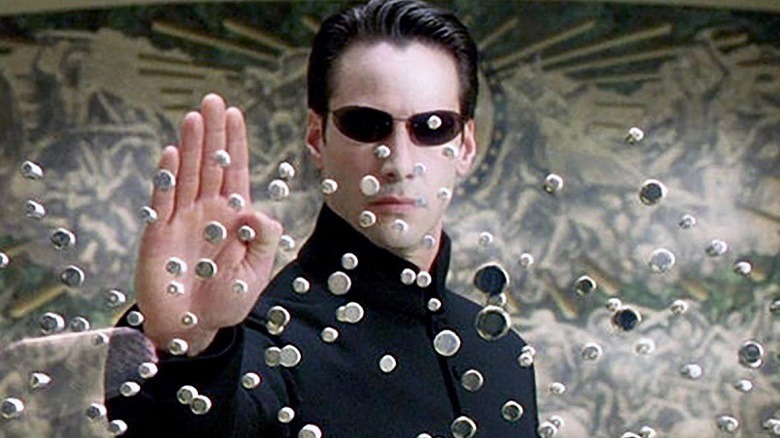

American History X (1998)

Another appearance of the underrated Edward Norton on this list, this 1998 drama is a grim and bleak look at racism and gang loyalty.

Norton plays Danny Vinyard, a brutal Neo-Nazi skinhead just out from prison after serving time for the murder of two Black youths who tried to carjack him. Released, he tries to prevent his younger brother from following in his Doc Marten-booted footsteps. Shot in two color schemes, the black and white sections show Vinyard's life as a Nazi, his racism only allowing him to see people as their skin tone, with the color half representing Vinyard post-prison and his ability to see the world as it is.

It's ultimately a tale of redemption but can only ever end in heartbreak. As a movie it's not without its flaws (Vinyard's Road to Damascus moment in jail is a little crudely managed) but it's a powerful work that if anything is even more relevant now than it was then. Despite having a notoriously bad experience whilst making the film with no love lost between director and Norton, director Tony Kaye is working on a pseudo-sequel of sorts in "African History Y."

Joker (2019)

There was a great deal of chatter about Todd Phillips' "Joker" prior to its release, namely casting aspersions on Phillips' credulity due to his comedic background, and also citing it as an origin story that nobody was asking for. They needn't have worried, because in "Joker" delivered something way more than a simple origin tale for the Crown Prince of Crime. Arthur Fleck — failed comedian, failed clown, failed human — finds his morality gradually eroded by the grim streets of Gotham City, inexorably descending into the insanity that will see him take the mantle of Batman's nemesis.

Looking like the movie Scorsese never quite got around to making, it's a tour de force of plot and performance. Joaquin Phoenix shines as the emaciated grease-painted protagonist, making a sympathetic character even as his deeds get darker. A mid-movie reveal trying to add connective tissue to the greater DC Universe falls somewhat flat, but the movie recovers from it admirably with another rug pull. If "Fight Club" is about men fighting to dispel the anger within them, "Joker" is about surrendering to it.

Heathers (1988)

The late '80s/early '90s bought us the term "Generation X." Typifying children born in the '70s and '80s, it represented a new breed of youth — kids with greater independence (due to increased divorce rates or both parents mostly absent at work) who were both tech-savvy, more liberal-leaning, and more suspicious of authority. A darker subset of movies appeared to represent their ideals, a spate of black, cynical comedies — "Heathers" was one such film, neatly making the X in Gen-X stand for "execution."

Popular high-school girl Veronica (Winona Ryder, surely one of the patron saints of Gen-X) gets together with bad boy boyfriend J.D. (Christian Slater). After the two of them accidentally poison the head of the "Heathers" clique, Veronica starts to suspect that J.D. might be deliberately killing students that he does not like.

A neat antidote to the occasional schmaltz of the era's John Hughes, "Heathers" is a delicious slice of high-school nihilism. Delightfully subversive, it puts disillusioned teens in the spotlight for once. It seemed the unlikeliest of movies to spawn a musical, but it goes to show the continuing strength of the work.

Hard Candy (2005)

Photographer Jeff (Patrick Wilson) and Hayley (Elliot Page) have been chatting online and flirting for a while, and agree to meet in person. Problem is, Jeff is 32 and Hayley is 14. After going back to his house after meeting in a coffee house, Hayley drugs Jeff. When he wakes up, he's bound to a chair. It's very possible that Jeff's crimes may well have been revealed.

This taut 2005 psychological drama is held together by the two central performances; Wilson and Page are both utterly convincing in their roles, and it would have been easy to fall into the accepted stereotypes of Wilson as despicable villain and Page as avenging angel, but the film is considerably less predictable than that. Elements of it may be uncomfortable viewing — especially for such a taboo subject in cinema — but there are plenty of surprises, and some surprising shifts in sympathy. It goes to some very dark places, and the story is driven to a point that you couldn't predict.

In Bruges (2008)

Having botched an assassination, Irish hitmen Ken (Brendan Gleeson) and Ray (Colin Farrell) are instructed by their boss Harry to lie low in Bruges, Belgium, and await further instructions. The tranquility of the tranquil Flemish town will soon be interrupted by attempted murder, sight-seeing with overweight tourists, and a racist dwarf.

If it's the dark humor of "Fight Club" you're after, this is a comedy as black as a priest's socks, with two stellar performances from the hilarious leads. Every scene with the two failed hitmen — two decidedly disparate personalities — is golden, and it's as watchable as it is quotable. Add a foul-mouthed Ralph Fiennes into the mix as their short-tempered boss, and you've got nigh-on cinematic perfection. The strong themes here are redemption and the importance of principles, and — oddly for a film about two men paid to kill other men — it's strangely poignant and uplifting.

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014)

Dealing with themes of both duality and identity that will ring true for those familiar with "Fight Club," "Birdman" is a 2014 black comedy set in and around a Broadway theatre, featuring an ensemble cast (and yet another appearance from trusty Ed Norton).

Riggan Thomson is a washed-up Hollywood actor, most famous for his role as the titular Birdman in a series of superhero films. He is attempting to make himself better known as a serious actor in his self-financed Broadway adaptation of a Raymond Carver short story. Following the days leading up to opening night, Thomson struggles with his confidence and individuality, as well as the manifestation of his superhero alter-ego — who begins to take physical winged form as Thomson's sanity flails. Not since "Being John Malkovich" has the soul and essence of an actor been laid so bare.

The incredibly versatile ex-Batman Michael Keaton is perfectly cast as Thomson, and the film is notable for both its all-star cast and an improvised jazz percussion soundtrack which acts as the very heartbeat of the film. Beautifully shot with long lingering takes, we can feel the frustration of Riggan in his flawed attempts to reinvent himself as a renaissance man, one who can write, direct, star and co-produce this ambitious performance. A wonderfully ambiguous ending tops off this delightful movie, and — like "Superman" — you'll believe that a man can fly.

Being John Malkovich (1999)

The first full-length film directed by Spike Jonze, who was known at the time for his quirky and distinctive music videos, "Being John Malkovich" is so high-concept as to be virtually stratospheric. Puppeteer Craig, forced through poverty to take a menial job at the offices of LesterCorp, finds a hidden portal in the wall that leads to the consciousness of John Malkovich. After half an hour of controlling the Oscar-nominated actor, he is rudely ejected and lands next to the New Jersey Turnpike.

Despite the incredibly bizarre premise, there is a surreal logic to it all, and a plot that unravels the reason behind the whole twisted set-up. If the exploration of self-identity in "Fight Club" intrigued you, "Being John Malkovich" will be right up your alley. Somewhat ironically, by taking up residence in Malkovich's cerebral cortex, various characters undergo a process of self-realization, unlocking their potential at the same time that the actor is locked out of his own psyche. And if it's simply Brad Pitt you're here for, well, he produced the movie, and pops up in a blink-and-you'll-miss-him cameo.

Se7en (1995)

A movie that should make us glad that unboxing videos didn't become popular until a decade later, "Se7en" is a gritty psychological thriller set in an unnamed, rain-drenched city. A serial killer is on the loose, choosing victims based on their violations of the seven deadly sins. Detective Somerset teams up with new transfer David Mills to find the perpetrator before he can claim his septuple victims.

Preceding both "The Game" and "Fight Club," "Se7en" is perhaps the bleakest film on David Fincher's resume — it's a truly nihilistic work with an ending that does the audience no favors. The predominant theme here is judgment; the killer (known only as "John Doe," reflecting both his mediocrity and his anonymity) is judging those he believes are guilty, and Somerset and Mills are trying to bring him to justice. It's the quest of the latter — and its inevitable, harrowing conclusion — that makes this film stand out, and that pegged Fincher as a talent to watch.

Rashômon (1950)

If the nature of the unreliable narrator in "Fight Club" appealed to you, "Rashômon," which tells the story of a murdered samurai and his sexually-assaulted wife from a variety of different viewpoints, has several. Akira Kurosawa's film reveals each character's version of the story via flashback — first, we hear from a bandit, then the samurai's wife, the samurai himself (channeled through a medium), and, finally, a woodcutter.

The tales overlap and intertwine, yet also contradict and undermine each other, offering no satisfactory answer at the movie's conclusion. Each person's account is utterly convincing, but only one can be accurate. Audiences will come away having drawn their own conclusions, with their opinion about "the truth" shaped by the words of biased storytellers. Ultimately, though, the film does end on a slightly redemptive note, arguing that honesty and decency can make the world a better place.

The film is considered so influential that it coined the term "The Rashômon Effect," describing the use of unreliable narrators to tell a story from multiple perspectives. It's a cinematic storytelling technique that has been used to significant effect in many films, several of which you'll find on this list.

Gone Girl (2014)

If you're familiar with the TV series "Succession" (and you really should be), you'll find some similarities here — namely, "Gone Girl" is a drama where the leads are unlikable, narcissistic psychopaths. Personality disorders are the order of the day in this David Fincher-directed psychological thriller, which is based on the hugely successful Gillian Flynn novel.

When writer Nick Dunne's wife Amy goes missing on the couples' fifth wedding anniversary, the subsequent media interest and police investigation reveal the truth lurking under their seemingly happy marriage, delving into a quagmire of duplicitousness, adultery, and lies, all hidden behind the facade of wedded bliss. Nick finds himself suspect number one in his wife's disappearance, and yet, as in "Hard Candy" (another film on this list), your sympathies will shift between Nick and his wife with each remorseless plot twist.

There's no denying that David Fincher favors a certain genre of film, and "Gone Girl" is no exception. With its unreliable narrators, issues surrounding identity, and a morass of overt and borderline psychological disorders, the book seems like a custom fit for the director of "Fight Club."

Inception (2010)

Before Christopher Nolan decided to attempt to scramble our frontal lobes into gray goo with "Tenet," he tested the waters with "Inception." In a not-so-distant future, it's possible to share dreams through technology, but this paradigm-shifting gizmo surprisingly isn't being monetized by the pornography industry. Instead, it's used for corporate espionage.

Don Cobb is an Extractor, a thief who uses this technology to extract sensitive information from corporate employees. He's tasked with assembling a team to perform an "Inception" – i.e., implanting a thought in somebody's mind — in order to make a business rival dissolve his company. What follows is a dizzying tale of sanity and gravity defying set-pieces, and an assault on a mountaintop fortress that'll make you regret that Nolan hasn't been allowed to direct a Bond film (yet, anyway).

It's a convoluted Russian nesting doll of dreams within dreams within dreams with a deliciously ambiguous ending that'll make you question the reality of what you've just watched. Nolan's films reward you for paying attention throughout, and this is definitely one film you don't want to fall asleep watching. Who knows where you'll end up?

Shutter Island (2010)

Martin Scorsese's film noir thriller, based on the 2003 Dennis Lehane novel of the same name, follows U.S. Marshall Teddy Daniels and his partner as they investigate an asylum located on the titular islet, seeking clues regarding a missing murderer.

Scorsese is clearly in his element in this particular genre, channeling Hitchcock with his shadowy and atmospheric shots, and "Shutter Island" is replete with all the elements you'd expect from a noir: lies, double-crosses, and a femme fatale in the form of the absconded murderess. Even the title of the film itself is an anagram of "truths and lies." Coincidence, or not?

Where "Fight Club" loosely dabbles with examining the nature of reality, "Shutter Island" plunges headlong into such a study. As Daniels' inquiry continues, he finds that he's essentially investigating himself, and must discover whether or not he's equipped to cope with what he finds. As we saw in "Memento," sometimes a protagonist learns that it's better not to know the truth. The whole film builds leads to a killer twist that you may well see coming, but it's no weaker a film for that — indeed, the nature of the rug-pull rewards a rewatch.

Nightcrawler (2014)

Where "Fight Club" takes satirical swipes at corporate America, "Nightcrawler" does the same with modern journalism. Louis Bloom starts a career as a "stringer," a freelance journalist who records footage of criminal activity and sells it to television news stations. Of course, the more unique and dramatic the footage, the greater its value.

Jake Gyllenhaal turns in a career-best performance as con man-turned-cameraman Bloom, whose lack of ethics gives him a distinct advantage in this career. As we witness Bloom's rise to fame, with scenes echoing Henry Hill's ascent in "Goodfellas," his deeds grow darker and darker; he'll go to any length to get salable footage.

Yet, unlike Henry Hill, Bloom suffers no fall from grace. In an industry driven by consumer demand, Bloom's lust for fame and riches is restrained only by his morality, which — unlike his grisly footage — is in short demand. Bill Paxton appears as rival stringer Joe, the yin to Bloom's yang; Joe introduces Bloom to the job, but he's the far more humane of the two partners.

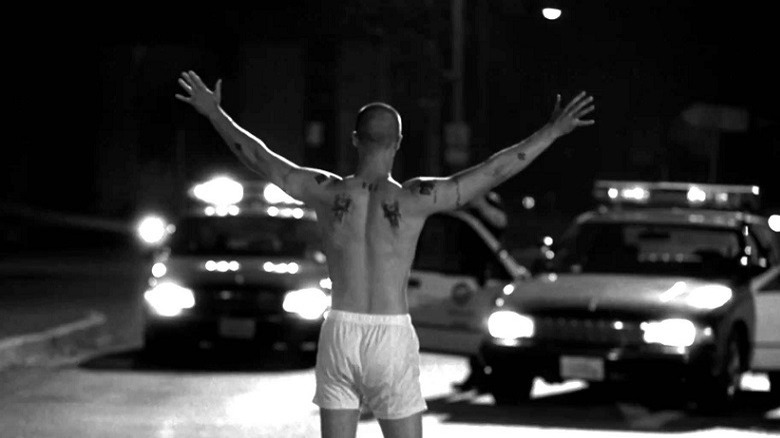

American Psycho (2000)

Patrick Bateman is a wealthy 27-year-old Wall Street employee with the world at his feet. Sadly, his wardrobe of killer suits is matched by his killer instincts — behind his handsome and charming façade lurks a penchant for cold-blooded murder.

Where "Wall Street" takes a wry look at the affluence and greed of the '80s, "American Psycho" wonders what would happen if even that wasn't enough. Based on the controversial 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis, "American Psycho" features a trope that's common to much of the writer's work: damaged characters who inhabit a flawed world.

On the surface, "American Psycho" shares satirical elements with "Fight Club," as both are transgressive pieces of fiction that star angry young men with psychological disorders. However, whereas it's possible to feel some sympathy for Ed Norton's narrator, it's difficult to eke out any for Bateman. He's an unlikable narcissist with a hair-trigger temper, and any audience would be forgiven for wanting to see this unpleasant figure face any form of justice. At the end, though, you're left to ponder whether Patrick's most profound mental disorder is his psychopathy or his inability to tell truth from fiction.

Taxi Driver (1976)

A film powerful enough to encourage an attempted presidential assassination, "Taxi Driver" is a squalid look at America's dark underbelly. As we follow the misadventures of reclusive New York cab driver Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), we watch as he spirals into an insanity that can only end in violence. His thoughts regarding vigilantism become ever more powerful and profound as he fails to readjust to civilian life after the end of the Vietnam War.

The influence of "Taxi Driver" is still felt today, with films such as Todd Phillip's "Joker" serving as a transparent homage to this particular worldview and specific flavor of antihero. Arthur Fleck's rat-and-crime infested Gotham and Bickle's New York are interchangeable.

The avenging antihero is a powerful motif in "Fight Club," and it recalls Travis' unfortunate story. There's an inevitability to his plight, and a voyeuristic quality in the audience's inability to look inward as he spirals deeper into delusion and madness. Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro would go on to make many movies together — the actor is arguably the director's number one muse — but never to better effect than in this poignant tragedy.

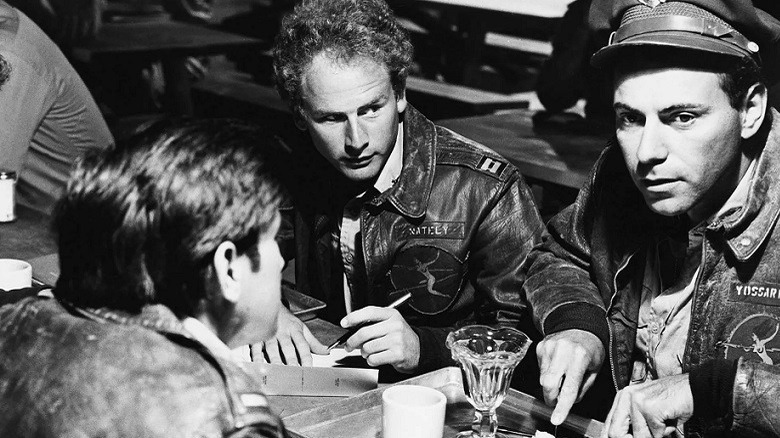

Catch-22 (1970)

Not only were Peter George's 1958 novel "Red Alert" and Joseph Heller's satirical classic "Catch-22" both written at around the same time, but they'd both go on to spawn classic — and not dissimilar — movies. "Red Alert" was filmed by Kubrick as "Dr. Strangelove" in 1964, with "Catch-22" released at the dawn of the '70s. Both are parodies of the bureaucratic irrationality surrounding the military-industrial complex, embracing the worrying concept that the people in charge of keeping us safe are the people least-suited for the job.

The catch-22 in the title comes from the plight of the film's protagonist, Captain Yossarian. Yossarian is a B-25 Bombardier in the employ of the American Air Force, who tries to stay alive by flying as few combat missions as possible. Heller coined the phrase for the novel, and uses it to describe a situation that can only be avoided through a paradoxical solution.

In both book and film, any pilot who claims they can't fly because they're mentally unstable is instantly judged as fit for duty; as the logic goes, only a sane person would make such a request. It's this dark gallows humor that saturates every frame of this classic movie, one that reminds us that some situations can only be laughed at — otherwise, you'd start crying, and you'd never stop.