The Ring Ending Explained: Analog Anxieties And Murderous Mothers

Released in 2002, Gore Verbinski's "The Ring" endures as a staple of teenage sleepover endurance testing. The very video that leaves a trail of deformed bodies in its wake is baked into the film itself, transforming the audience from impartial viewer to imminent victim of the cursed tape's supernatural powers. An adaptation of the 1998 Japanese film "Ringu" directed by Hideo Nakata (which itself is based on the 1991 Koji Suzuku novel of the same name), the critical and commercial success of "The Ring" paved the way for a slew of American J-horror remakes in the aughts, including "The Grudge," "Dark Water," "Shutter" and "The Eye."

Still, "The Ring" prevails above all others as the most culturally ubiquitous of this era of mainstream horror, particularly due to the film's brutal break-neck ending. Several themes surrounding human anxieties — past and perennial — imbue the ending with pointed messages while re-submerging viewers in a horrifying pit of despair after they've just come up to raggedly gasp for air.

What exactly happened in The Ring, anyway?

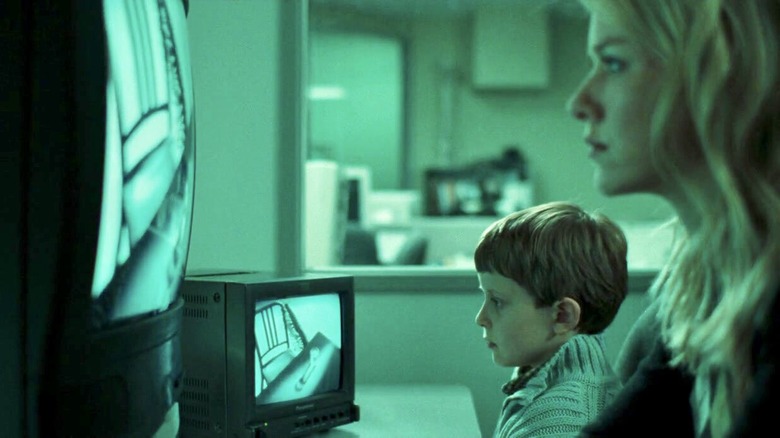

When her 16-year-old niece Katie unexpectedly dies, journalist Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts) is determined to find answers. Strangely, Rachel's niece isn't the only sudden teen death in the Seattle neighborhood. Katie and her friends rented a cabin a week before their collective demise, prompting Rachel to rent the same room they occupied. She finds an unlabeled tape, which turns out to be a sequence of bleak, disturbing images. When the tape ends, she receives a call: "Seven days," a voice whispers. Spooked and beginning to put the terrifying pieces together, she asks her ex Noah for help, making him a copy of the tape to study. When Rachel's son Aidan is also exposed to the images, she races to quell the curse before it eventually claims their lives.

The tape was created via the telekinetic powers of Samara, a troubled girl adopted by a couple who bred prized racehorses. When Samara drove a stable of horses to mass suicide, her mother threw her down a well before taking her own life. It takes seven days submerged in chilling water before Samara dies, one of her last sights being the pale circle of daylight that seeps around the lid of her crude tomb — the film's titular ring and the last shot of the ominous tape.

It turns out that the cabin itself is built over the well Samara died in. After Rachel accidentally falls in, she cradles the reanimated body of Samara, who seems finally at peace. The seven-day deadline passes for Rachel with no incident. All appears well — that is, until Noah's maimed body is found in his studio, signaling Aidan as next in line for demise. Yet Rachel has an epiphany just in time: She realizes that by copying the tape and passing it on to someone else, she was spared death. Solemnly, she instructs Aidan to make a copy for an unsuspecting future viewer, alleviating the literal grip of the curse on her son.

A fear of the technological unknown

Though Samara's scorned spirit is what literally kills people, the tape itself is the undeniable object of fear. This is an apt allegory for the anxieties of the burgeoning technological dependence of the so-called "developed" world. For one, technology itself can be a harbinger of death and destruction: Creations such as the atomic bomb and drones have been heralded as scientific achievements while concurrently snuffing out innocent human lives. Particularly when considering the story's roots in Japan — the only country to have been subjected to nuclear warfare — this fear is not unsubstantiated. When a piece of technology's only use is to inflict harm, the fear of being targeted without individual provocation is horrifying.

There's also the looming threat of Y2K in the original "Ringu," with "The Ring" being released two years after the world scrambled to prepare for (falsely) approaching technological doom. Though largely unconcerned with the Internet and computers, "The Ring" certainly serves as an early warning against consuming unknown morsels of media. Certainly, the iconic SmileDog.jpg creepypasta emulated this—along with the callous, self-saving realization that sharing the source of horror with an unsuspecting spectator will alleviate the hellish confines of image-based curses.

Of course, the encroaching ubiquity of technology also means that scary things are simply easier to share, and "The Ring" was, in many ways, eerily prophetic. See the newfound concept of "doom scrolling" — the world's horrors are easier to consume than ever, many of us self-inflicting these sickening facets of media onto ourselves. Dead bodies of state-sanctioned violence permeate Twitter feeds while endless environmental catastrophes dominate headlines and "For You" pages.

Mother as monstrous murderer

There's also the parallel of work-obsessed moms in "The Ring," with some disquieting similarities between Samara's mom and Rachel. Both end up neglecting their children while in the line of duty — Rachel's absence unintentionally causes Aiden to watch the killer tape, while the horse breeder becomes so attached to her animals that she avenges their lives by taking her daughter's. Both of their children are also faced with death within a seven-day timeline. Samara sinks to the bottom of a well; Aidan treads metaphorical water as his demonic deadline fast approaches.

Though it appears that Rachel saves her son through work while Samara's mother kills her to get even for it, both mothers are undeniably murderers. Rachel never lays her hands on another person's throat (unlike Samara's mother does to her daughter), but she does willingly perpetuate the curse in order to salvage her son's life. The flim's ending thus raises the following questions: What constitutes a "good mother" or a "bad child" anyway? How do our individual instincts affect our decisions? Is revenge truly merited in any of its iterations? By way of a sinister and morally murky ending, "The Ring" refuses to let anyone off the hook. The survival of ourselves and our loved ones just might mean the death of a stranger — who would you rather sacrifice?