The French Dispatch Review: Wes Anderson's Stylish Love Letter Never Buries The Lead

When you start a job in at a newspaper, you start at the bottom. As an intern at the Washington Post, that meant I was dropped right into Obituaries, where a sour-faced editor who obviously would rather be writing at the New York Times carved a bloody streak of red pen across every story I filed. It was a strange feeling, to start working at one of the biggest national newspapers to have its fingers on the pulse of America, and to be writing about dead people. When I asked my editor why that was, why Obits was where we had to pay our dues, he replied that by writing obituaries, it's where you learn to really write about people. The things they did, the things they loved, the people they left behind. An obituary was a chance to take a name and turn it into a story.

Wes Anderson's stoically stylish "The French Dispatch" begins and ends with a death: the death of a newspaper, and the death of the inspired man who started it. Arthur Howitzer Jr. (a scarce but impishly warm Bill Murray) founded the eponymous newspaper as a way of bringing the glamorous world of France to the people of his home state of Kansas. But what he got from his quirky, larger-than-life staff of reporters was something much more off-beat — and infinitely better.

Telling Several Stories With Style

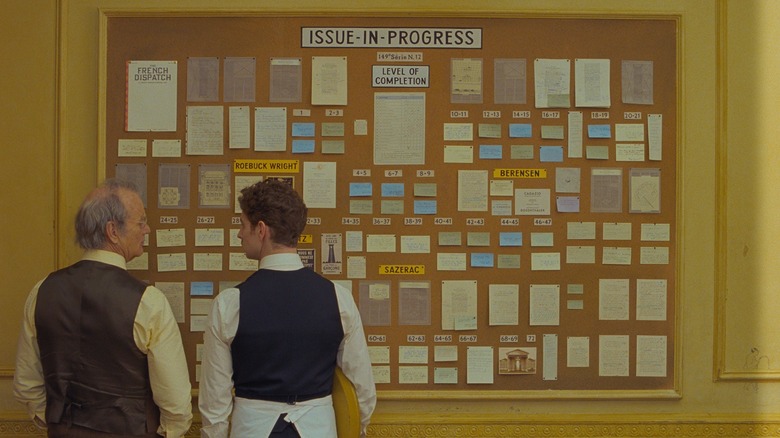

Owen Wilson's Cycling Reporter Herbsaint Sazerac is tasked with the simple pitch of writing about the residents of Ennui-sur-Blasé (which hilariously translates to "Boredom-on-Blasé"), but turns a slice-of-life fluff piece into a rich tapestry of the drunks, whores, and drug dealers of the fictional French city. Tilda Swinton's self-important staff writer J.K.L. Berensen is given the job about writing of the elusive art of incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro), and files an indulgent erotic tale of a prisoner in love with his prison guard (Lea Seydoux, at her icy best), and a harried art dealer (Adrien Brody, always game) who sees money in starting a whole new art movement. Frances McDormand's Miss Lonelyhearts journalist, Lucinda Krementz, falls behind the picket line and into bed with a student revolutionary (a perfectly guileless Timothée Chalamet, making magic with yet another auteur director) after she is sent to report on their fruitless efforts for change. And for Jeffrey Wright's nebbish food journalist Roebuck Wright, what starts as an assignment to profile a gourmet chef for the police (Stephen Park, speaking all of two lines?) turns into a thrilling kidnapping case that involves mobsters, showgirls (Saoirse Ronan, injecting warmth into a bit part), and underworld accountants (Willem Dafoe, likewise).

Each vignette is as packed with the same amount of meticulous detail and immaculately clipped dialogue delivery as a full-fledged Anderson movie. The visual language changes from vignette to vignette, some a pleasant pastel; some pop with bright, saturated colors; some in black-and-white; some a fantastical blend of both. It's Anderson, 25 years into his career, flexing every stylistic trick in his pocket, and then some.

To call "The French Dispatch" a visual feast feels like a gross understatement — a visual assault might be more accurate. But it's one that is less about assaulting the senses than it is about overloading it — each frame of the film is packed to the gills with stuff. All the same, while "assault" might suggest something violent and unpleasant, "The French Dispatch" is nothing but pleasant to look at in the most Andersonian way. All of Anderson's stylistic quirks are turned up to 11 in this film; his pop-up book aesthetic, but one where each page explodes with glitter and flowers and tinny saxophone music, and somehow, real fireworks. It's like the pristine art of a New Yorker cover crossed with the chaos of a "Where's Waldo" picture: oversaturated and overstuffed and artificial and absolutely delightful to behold.

No Crying in the Newsroom

"The French Dispatch" is so breathlessly stylized that one might accuse it of being airless and emotionally inert (and indeed, many have). But that's not the case at all. As visually overwhelming and artfully engineered a film as "The French Dispatch" is, it's also one of secret warmth lurking beneath the surface. It's in the way each reporter takes a simple assignment and turns it into a story, one that takes on its own life and one in which the people within it become more than the archetypes they began as. One where the reporters inevitably get involved themselves, participants in the story and not simple observers — Wright's Roebuck pondering the sadness of the final quote from his chef subject, McDormand mourning the brevity of youth with the tragic end to her student revolutionary piece. Like a New Yorker cover, the film may at first seem stiff and unwelcoming, but it offers infinite riches and emotional clarity beneath the surface.

It reminded me, in a sense, of writing obituaries — which fittingly, is where "The French Dispatch" ends, with the grieving staff of the newspaper gathering to write the obituary for Murray's strict but disarmingly compassionate editor-in-chief. These stories, in their artfully constructed archetypes and clichés, are simply windows into the characters and lives that we only get glimpses of. "The French Dispatch" doesn't go all the way into exploring those lives, but just the hint of is it enough.

"No crying in the newsroom" is a sign that hangs above Arthur Howitzer Jr.'s office door, as if to telegraph the kind of emotional distance that Anderson practices with "The French Dispatch." Buy cry the staff does, and feel we do, fair and unbiased reporting be damned.

/Film Rating: 9 out of 10