Gone Girl Ending Explained: For Better Or Worse, Til Death Do Us Part

Crime media is all the rage. For 2023, crime and genre television dominated the Netflix streaming charts, according to a CNBC report. Audiences want dark. They want complicated heroes wading through the muck of modern society. Expectedly, there's a kind of catharis in juxtaposing the ailments of the real world with the augmented woes of a fictional one. Few creatives do that quite as well as Gillian Flynn. While her early written works were a remarkable success, Flynn's mainstream breakout undoubtedly came with the 2012 publication of "Gone Girl," her third novel, and director David Fincher's 2014 feature of the same name.

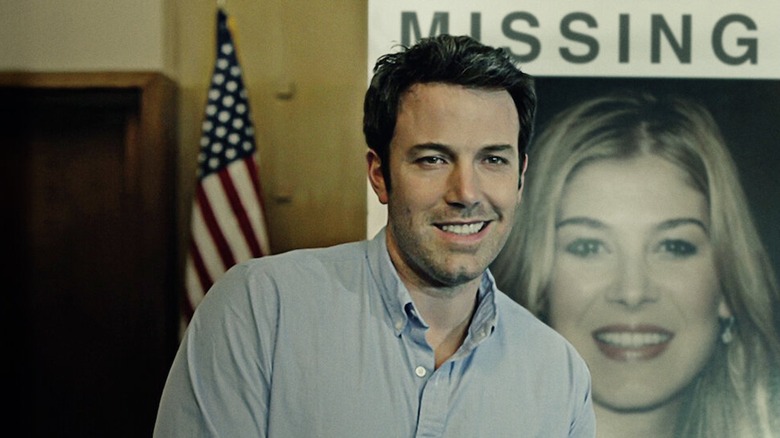

A commercial and critical success — star Rosamund Pike was nominated for an Academy Award for her performance — "Gone Girl" was the movie everyone couldn't stop talking about. Core to those conversations was its daring, subversive ending. Audiences expect the villain to be punished. In "Gone Girl," after her plan to fake her death and frame her husband Nick (Ben Affleck) for murder ends up spoiled but not entirely ruined, mastermind Amy Dunne (Pike) concocts one final scheme as the credits roll. She artificially inseminates herself with Nick's sperm, trapping him in their marriage for the foreseeable future.

While the ending fits thematically within the broader framework of "Gone Girl's" interrogation of modern marriage, it nonetheless got people talking, no differently than the ending of "Sharp Objects," another exceptional Flynn adaptation. Here, we'll be unpacking the ending to "Gone Girl," assessing what it means and contextualizing it within the larger body of Flynn's work.

Amy staged her disappearance

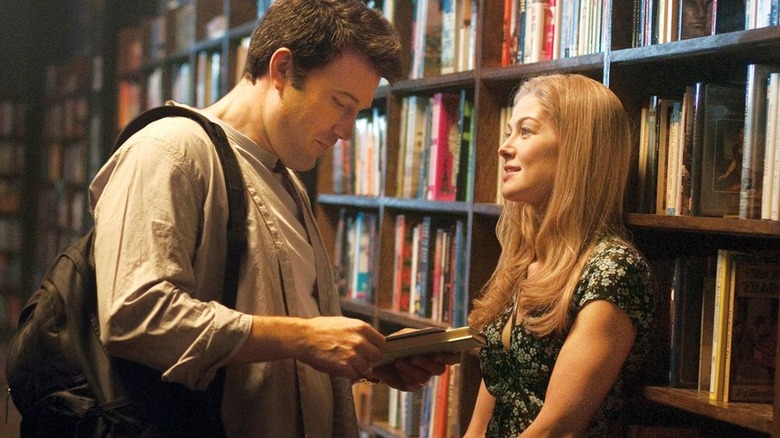

First, it's worth revisiting what actually transpires during the dense 150-minute runtime of "Gone Girl." Director David Fincher, borrowing the novel's dual points-of-view, first introduces audiences to cad of a husband Nick Dunne. He and Amy have moved to his hometown of North Carthage, Missouri after Nick augments recession woes with blatantly irresponsible spending. There, he sets up shop in a local bar, teaching on the side, all the while cheating on his wife. He's an affable dolt, and neither Flynn's writing nor Fincher's direction conceal his impressionable charisma. For all his faults, he's kind of charming. On writing Nick, Flynn remarked to The Guardian, "He just needs to be a believable person. It helped giving him a biography close to mine."

It's his and Amy's fifth wedding anniversary, though when Nick arrives home, he finds signs of a struggle. Worse still, Amy is missing. So begins an homage to the real-life disappearance and murder of Laci Peterson – but Flynn has a twist up her sleeve. Amy staged her own disappearance to punish Nick, certain he'd be both tried and convicted. Nick mounts his defense as Amy remotely responds to his every move. It's a noxious, twisted game of chess where both players, whether they'd like to admit it or not, know the other better than anyone. Marriage never seemed like a worse idea.

Nick and Amy: Til death do them part

As "Gone Girl" veers into its third act, the stage is set. Amy seeks refuge with adolescent friend (stalker) Desi (Neil Patrick Harris) after she is robbed and left with few resources to continue her charade. She paints an incredulous portrait of domestic abuse to win over Desi's sympathies, but Desi isn't above water, either, treating Amy more as a captive than a friend. Nick, meanwhile, plans a televised interview with Nancy Grace stand-in Ellen Abbott (Missi Pyle), both a ploy to win over public sympathy and bait Amy into coming home. It works. Amy kills Desi, stages his home to pin him as the ultimate mastermind, and returns home covered in blood. The happy couple is reunited.

Ostensibly, at least. Nick isn't alone in knowing about Amy's scheme. His sister Margo (Carrie Coon) and Detective Boney (Kim Dickens) are eager to have her apprehended, but Nick surprises everyone when he announces his plan to stay with Amy. Targeting the core of the novel, Nick and Amy will masquerade domestic bliss. That insidious undercurrent runs throughout, the suggestion that spouses never really know one another. It's all pretend, a matter of acting, and both roles need to convince for the charade to work. It's an uneasy, chilling ending, and in an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Gillian Flynn revealed she intended it to be that way, remarking, "I did think it all through, and for me, I've always loved those endings of unease."

Nick and Amy are meant for each other

Both "Gone Girl" the movie and "Gone Girl" the book end in roughly the same place. Amy returns home and uses her artificial pregnancy to entrap Nick. While the book suggests, courtesy of Desi's mom having a meltdown, that Amy might one day face retribution for her crimes, the movie eschews all doubt. Amy is free, and Nick delivers a chilling final line, saying to Amy, "What have we done to each other? What will we do?"

Nick's state of mind at the end is where "Gone Girl" unfurls into a frightening cocktail of modern relationship woes and, interestingly, the work of Erving Goffman, namely face-work. Face-work, per Goffman, is broadly the social value a person cultivates by acting a certain way. While "Gone Girl" gives the impression Nick stays with Amy to theoretically "save face," so to speak, there is a beguiling suggestion, courtesy of both Flynn's writing and Affleck's performance (whose real life baggage actually made him perfect for the role), that suggests otherwise.

In luring Amy home — in finally learning more about her, atoning for his own misdeeds as a husband — he's arguably fallen in love with her, his "Amazing Amy," all over again. Nick and Amy know one another better than anyone, and as violent and sick as their relationship might be, they don't want anyone else. They were made for each other, interstate crime spree and all.

Gone Girl bucks thriller convention

Gillian Flynn's scripted ending for "Gone Girl" works remarkably well thematically, though it is, in Flynn's own words, the only ending that narratively made sense. It's easy to forget that movies, especially mid-budget wide-release thrillers based on best-selling novels, are often products before they're art. I'm sure 20th Century Fox was impressed with the twisted artistry of Flynn's writing, but they were likely more impressed with the capacity for "Gone Girl" to sell tickets. Making $369 million worldwide against a $61 million budget is evidence enough.

Hegemonically, there's an understandable impulse in crime cinema, especially domestic crime cinema, to see the villains punished. They need to be apprehended, a la Norman Bates in "Psycho," or killed like Buffalo Bill in "The Silence of the Lambs." That wouldn't quite work for "Gone Girl," however. Speaking with Entertainment Weekly, Gillian Flynn said, "People think they would find that satisfying, if she were caught and punished... I promise you, I just don't think you'd find it satisfying for Amy to end up in a prison cell just sitting in a little box."

Asian crime thrillers – think "Oldboy," "I Saw the Devil," or even the incredible "Parasite" — for instance, regularly end on grim notes. That puts "Gone Girl" in league with some of the best that contemporary cinema has to offer. Killing Amy or sending her to jail is what audiences would expect. In doing so, "Gone Girl" would have ended up so much worse, so much more conventional.

Narcissism runs rampant

Amy Dunne is a complicated character, though she is also, at her core, a narcissist. In an interview with Collider, star Rosamund Pike touched on Amy's character, namely her childhood as the inspiration for a series of successful novels, remarking, "That's a recipe for narcissism, right there, because you're entitled and you feel inadequate. Then, that makes a very insecure adult, who simultaneously has very high expectations of themselves and others. That, for me, was my in into the character." Amy's final move—her trump card—was a pregnancy to keep Nick around. For Amy, it's less about the risk of jail, more about the risk of devouring her own reputation. Jail wouldn't scare Amy—being abandoned would.

For his part, Ben Affleck remarked to the Detroit Free Press, "I think for David this was a movie about how we sort of wear masks when we're in the process of getting into a relationship with somebody, and then we close the door and the masks come off and we find out who the other person really is, and that sometimes can be dark and scary." At an Oscar Nominee luncheon, however, Pike expanded, nailing the film's key idea, sharing with reporters, "These two narcissists got exactly what they deserve: they got each other." There is no Nick without Amy, and there is no Amy without Nick. They both made sure of that.

An indictment of true crime culture

"Gone Girl," while very of its time, proved remarkably prescient. As Hollywood reckons with its longstanding history of releasing exploitative true crime content, "Gone Girl" resonates considerably more. Characters like Casey Wilson's Noëlle Hawthorne conceptualize "Gone Girl's" subtextual indictment of true crime fandom, of the way it invites periphery characters into its orbit, allowing them to center themselves in stories that aren't about them. Flynn's writing is conspicuously critical of true crime culture, a culture that monetizes and fetishizes violence against women (especially white women).

Missi Pyle's Ellen Abbott is there to drag the Amy saga out, arbitrarily shifting from Nick's biggest ally to his most damning critic. Amy's story is regularly framed through a remunerative lens. Whatever sells is what the media writ large chooses to run with. Amy might be psychopathic, but she is also devilishly intelligent. Amy's clues, the nuggets she spreads around town that lead the police to Nick, are left with an adroit awareness of what sells— of what makes a good story. Exploitation is the point, and it cultivates an environment where Amy can get away with what she does. In a sickening twist of fate, some law enforcement missed the point, interpreting "Gone Girl" as a how-to-guide rather than an indictment of the American true crime ecosystem.

Dark Places and Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman

"Gone Girl" was, inceptively, a one-off. While we exist in a franchise landscape, there is little reason to further explore the world of Nick and Amy. The ending of "Gone Girl" is pitch-perfect, and a follow-up stands to only undermine the perverse efficacy of its concluding note. This girl can't go missing again.

In 2015, Flynn wasn't unequivocally opposed to the idea, sharing at the BAFTA LA Annual Awards Season Tea Party, "There could be a sequel at some point, if everyone is game to get the gang back together, it could be really fun a few years from now." More recently, in an interview with People Magazine for the novel's anniversary in 2022, Flynn said, "I may indeed want to go back in and update and play around with what the hell would've happened once Amy was a mom." Meanwhile, Rosamund Pike, remarked in no uncertain terms remarked, "No," when USA Today asked about the possibility she might return for a sequel.

"Gone Girl" fans might not see Amy and Nick together again on-screen, but they can at least look forward to "Dark Places," Flynn's forthcoming (and second) adaptation of her novel of the same name. For fans looking for something more B-movie-like, Flynn has reportedly written a script for Tim Burton's remake of "Attack of the Fifty-Foot Woman."

The only way

In the months before "Gone Girl" was officially released, fan speculation was running wild with an unfounded rumor. Reportedly, author and screenwriter Gillian Flynn had changed the ending. What could it be? How might things pan out differently? Well, those claims, in Flynn's own words, had been "greatly exaggerated" according to a Reddit AMA.

How much does the scripted ending change the novel's? Not much. While it's been touched on above how "Gone Girl" the book texturizes some concluding notes, including the addition of Desi's mom and Nick's more overt hostility toward Amy, the broad scope remains exactly the same. In both filmed and written form, Amy and Nick end the novel together.

Now, while I'm reticent to suggest "Gone Girl" improves upon the book's ending, its more nuanced, quiet conclusion better augments the story's thematic heft. Nick's antagonism toward Amy might be more generally satisfying, but harkening back to star Pike's own words, both Amy and Nick deserve one another. Amy is a product of Nick as much as she is a product of him. He bears responsibility, in some small measurement, for the dissolution of their marriage. Remember, Nick Dunne begins "Gone Girls" engaged in a long-running affair with a student of his. Movie Nick acquiesces less than accepts what he secretly wants. That's a chilling, resonant note to end on, and I wouldn't want it any other way.

If you like "Gone Girl," here are some other movies you might want to check out.