14 Remakes That Are Better Than The Original

In this day and age, it's amazingly easy to be a cynic. It could be argued that remakes are lazy cash-ins, that they're a sign of the lack of original ideas left in cinema, or that they exist only to appease that sizable portion of the cinema-going audience that needs to see films in their native tongue, without subtitles.

That's true in a great many cases (I'm looking at you, "Jacob's Ladder," "Quarantine," and "The Fog"), and yet there are times when a remake is a golden opportunity to do something bigger and better, or to revisit an idea that never got the audience it deserved. In fact, it's surprisingly common to find examples of remakes that work really well — there are even a handful that improve upon the original films (but don't worry; Gus Van Sant's critically loathed shot-for-shot remake of "Psycho," one of the most beloved movies ever made, will not be featured here). These are a few of them.

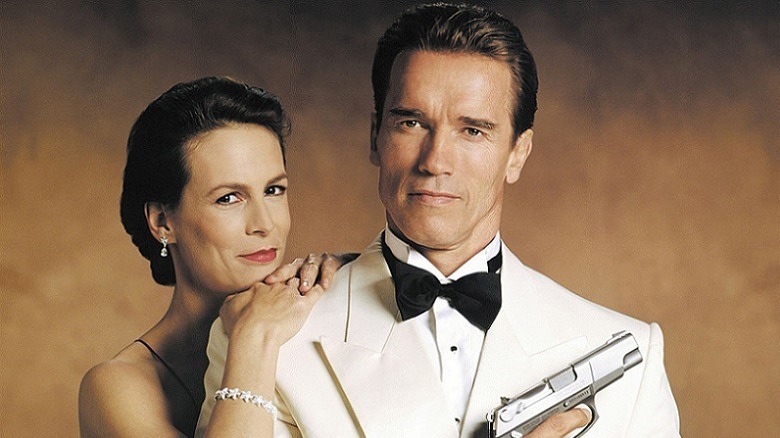

True Lies

Based on the 1991 French spy comedy "La Totale!," "True Lies" is an oft-forgotten James Cameron film that follows the exploits of a husband and father who, unknown to his family, just happens to be a secret agent trying to save the world. Ignoring the fact that it's difficult to believe that somebody like Arnold Schwarzenegger could ever blend in as a normal husband and father, "True Lies," like the original, is a fun and entertaining romp; as you'd expect, Cameron ups the stakes with incredible stunt work and action set pieces.

History hasn't been particularly kind to "True Lies" — a scene in which Arnold interrogates his wife (Jamie Lee Curtis) in secret and forces her to do a sensual dance that comes across as abusive and creepy now, and it's yet another '90s action movie with generic Arab bad guys. That said, "True Lies" remains eminently watchable. Cameron regular Bill Paxton is clearly having the time of his life as a used-car salesman pretending to be a secret agent, and it sets itself up nicely for a sequel that sadly never materialized (although rumors about a TV spin-off still persist).

War of the Worlds

We're still waiting patiently for a decent movie adaptation of H. G. Wells' 1898 novel material set in the Victorian era. The BBC released a flawed and mediocre three-part TV adaptation of the book back in 2019, but nobody seems to have gotten it right quite yet.

Some movies get close, though. George Pal released the first "War of the Worlds" movie in 1953, giving it a contemporary setting and moving it to America. The beats are the same as those of the novel, but the aliens themselves are a disappointment — rather than the distinctive tripods of the novel, they're piloting spaceships. Due to this, "War of the Worlds" feels like another, generic "Earth versus flying saucers" film of the '50s.

By contrast, Spielberg's 2005 update keeps the contemporary timeline and the American setting, but brings back the tripods — vast and towering, with ominous and terrifying silhouettes. From the brutal and overwhelming first attack wave through to abrupt end, in which the Martians' war plans crumble as a direct result of their anti-vaccination mindset (If you've avoided spoilers for more than a century and I've ruined the ending, I can only apologize), Spielberg shows us the entire war. Tom Cruise, despite his star-power, plays a convincing everyman. It's not perfect — Cruise and his son appear to possess either incredible luck or immortality — but it'll do until the perfect Victorian adaption comes along.

Heat

This is an unusual one. The classic 1995 crime drama — notorious for featuring the first proper dialogue scene between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino — is a remake of one of writer-director Michael Mann's own movies. "L.A. Takedown," originally a two-part pilot episode for a proposed series, was reworked into a TV movie that aired in 1989.

Both "Heat" and "L.A. Takedown" tell the tale of a dedicated homicide detective who hunts down a gang of professional thieves led by an enigmatic boss. Both men are two sides of the same coin, and it's the interesting nature of their symbiotic relationship that forms the crux of the film — interestingly, we have a certain sympathy with the villain, while the cop and his methods are far from perfect.

In hindsight, "L.A. Takedown" feels like a prototype. With the benefit of a $60 million budget, "Heat" is more refined, makes the most of newly introduced sub-plots, and has the significant star power of De Niro and Pacino behind it. The aforementioned scene between the two actors is cinema history; the iconic bank robbery is so well observed that it was used by the military to show how to effectively coordinate combat troops.

I Am Legend

The 1954 novel "I Am Legend" had already been adapted twice for the big screen before, once as Vincent Price's "The Last Man on Earth," and again as Charlton Heston's "The Omega Man." All three movies share a common story: that of the last survivor on Earth after a plague has turned the rest of humanity into feral creatures. The original two films, while fine, are flawed. The usually reliable Price was miscast in the first one, and the latter is weakened by underpowered antagonists.

There's no such danger in Will Smith's take on the story. Here, the "Darkseekers" are vampiric ghouls, shunning sunlight but armed with preternatural senses, speed, strength, and endurance. They hunt in packs and are genuinely terrifying, albeit a little over CGI-ed.

The Will Smith vehicle isn't without its flaws. The premise of the book is that the hero realizes that he has been the true villain all long; the ending of the 2007 movie removes this aspect completely (although the home video release does contain an alternate conclusion). Still, "I Am Legend" depicts a convincing dead Earth, and contains an excellent performance by Will Smith.

The Fly

The original 1958 version of "The Fly" always towered over the other mad scientist films from the same era, elevated by both Vincent Price and a truly chilling ending that shows the other victim of the film's teleporter accident: a tiny fly with a human head who pleads for his life as he struggles to free himself from a spider's web.

Cronenberg takes that same premise — a rogue fly in a teleporter pod causes trouble — and gives it the body-horror twist at which the horror maestro excels. In the 1986 remake, rather than split the subject into two distinct entities, doomed scientist Seth Brundle starts to metamorphose, his DNA merging with that of the wayward musca domestica.

Not simply a great remake, but one of the best horror films of the '80s, "The Fly" is one of the more mainstream movies in Cronenberg's loaded portfolio. It's hard to think of anybody better than Jeff Goldblum for the role — he brings just the right level of eccentricity to the film, but remains sympathetic enough throughout. The original is a great B-movie monster flick. The remake is a smart and sophisticated horror film with just enough "ick" to keep the gore-hounds happy.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

The 1956 version of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," based on the novel by author Jack Finney, is a stone-cold classic. Telling a subtler alien invasion story than audiences in the '50s were used to, it's a tale of conspiracy and paranoia. Humanity is being replaced by spores from space, which grow into duplicates that are indistinguishable from the original people, aside from the fact that they're emotionless. It's a striking, if unsubtle, political metaphor, calling out the supposed creep of communism and left-wing paranoia about the rise of McCarthyism.

The '70s remake treads a similar path, although we get to see the grisly pod-making process in all its gruesome detail. Like many films from its era, "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" is darkly nihilistic. The original ends on an optimistic note, with the hero, played by Kevin McCarthy, convincing others of the alien threat. The remake sees him cameo as the same character, although he meets with a darker fate. The bad guys won a lot in the '70s.

"The Body Snatchers" was revisited in 1993 by director Abel Ferrera, who made a smaller scale but surprisingly good movie, and again to lesser results in 2007's "The Invasion."

The Birdcage

A remake of the 1978 Franco-Italian film "La Cage aux Folles," "The Birdcage" is a comedy about Albert and Armand, two flamboyant gay people who have to pretend to be a straight married couple to appease their son's fiancée's puritanical parents.

Both original and remake are excellent, with Mike Nichols' 1996 remake just edging ahead thanks to the perfect casting of Robin Williams and Nathan Lane. Lane is uproarious in a role originally intended for Williams, who turned it down due to having just filmed "Mrs. Doubtfire" (Lane spends almost the entire movie in drag).

The movie is a classic farce with all of the elements that genre entails: mistaken identities, slapstick, and an improbable situation that leads to increasingly outlandish comedic scenes. Robin Williams is as dependable as ever, reminding the audience what a great comedic talent we lost with a role that carries a surprising amount of poignancy. Gene Hackman and Dianne West play the conservative parents with great gusto, and there's a wonderful inspirational — and surprisingly prescient — theme to what initially seems like a throwaway comedy.

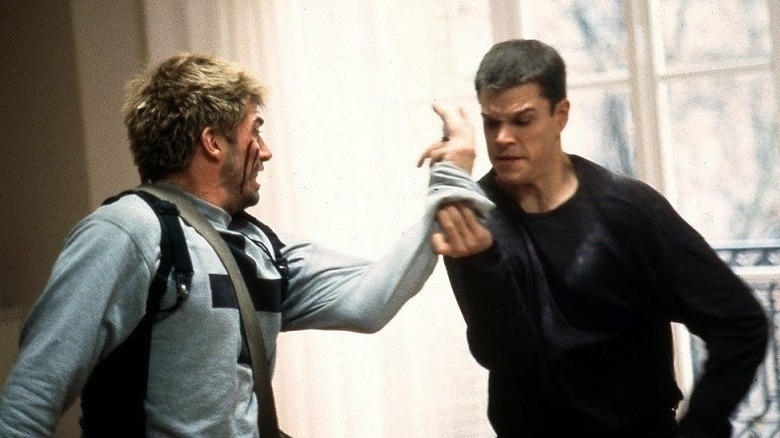

The Bourne Identity

The first adaption of Robert Ludlum's 1980 novel was a two-part made-for-TV movie originally shown back in 1988 that starred Richard Chamberlain as the titular superspy. Both 2002 movie and TV series tread similar ground, with the protagonist trying to piece together his life after one of those bouts of amnesia that mostly seem to happen in movies. However, the TV version is less dark, and all its plotlines are neatly resolved at the end — unlike the ambiguous conclusion of the first Damon movie, which led on to a number of sequels.

Chamberlain, always an excellent actor, is perfectly adequate as Bourne, and his film is a perfectly watchable spy romp. But Damon's movie has novel set pieces, a wonderfully convoluted plot, and — most importantly — redefined spy cinema for the new century. "The Bourne Identity" had a major influence on the Daniel Craig-led Bond reboot, which saw 007 move away from gadgetry and more towards the spycraft of Ian Fleming's original novels; without the success of "The Bourne Identity," we probably wouldn't have "Casino Royale," "Skyfall," and the rest.

The Thing

"The Thing," a remake of the 1951 film "The Thing from Another World," based on the classic novella by John W. Campbell, is a masterpiece. The original movie is a competent enough science-fiction adventure, but radically changes the nature of the antagonist from the source material, and is the poorer film for it. See, in the 1951 version, the titular thing is a vegetative lifeform that feeds on blood — one character calls it a "super carrot" — and is basically reduced to a generic monster movie with a man in a costume.

By contrast, John Carpenter's remake takes the original's tight plot and crackling dialogue and reintroduces the novella's thawed-out foe. In doing so, Carpenter adds a level of paranoia and tension that the original struggles to maintain. Add in exemplary practical effects work, and Carpenter's version of the story is the superior one by far. It's closer to the source material, and remains a movie that holds up today (but let's not talk about the prequel).

The Maltese Falcon

One of the very first examples of film noir, 1941's "The Maltese Falcon" was released just a decade after the original. It's notable for being the first appearance of Humphrey Bogart as tough hard-boiled detective Sam Spade, whose character and demeanor would go on to be highly influential on the genre as a whole.

This remake is closer to the source material (a novel of the same name, published by Dashiell Hammett in 1930), and is by far the greater film in every regard, but the history behind why this was remade in the first place is interesting. The original "The Maltese Falcon" was shot before the introduction of the Hays Production Code in Hollywood, and wasn't able to be screened because of unsavory content (most notably, lots sexual innuendo and some almost-nudity). That being said, the 1941 film is Hammett's favorite adaption of his work — seriously, who's to argue with him?

The Mummy

The original "The Mummy," released in 1932, is a classic, but it's also one of the weaker Universal monster movies. The bandaged Imhotep always seemed like a second-stringer in comparison to his fanged, lycanthrope, amphibian, and bolt-necked cousins.

It's interesting to note that Brendan Fraser-led remake, like the doomed Tom Cruise movie, was intended to be a horror movie. At one stage, directors like George A. Romero and Clive Barker were attached. However, after an age in development hell, "The Mummy" became a swashbuckling adventure, more "Raiders of the Lost Ark" than "Return of the Living Dead."

The series is guilty of ever-diminishing returns and an execrable spin-off in "The Scorpion King," but the first movie emerged out of nowhere and felt like a genuine revelation. Fresh-faced Fraser was a star in ascendance as the square-jawed all-American hero Rick O'Connell, and it's a movie as fun as it is loud and entertaining. My preference for the 1999 remake may be shallow, but even horror royalty like Boris Karloff can't save the original from being a plodding and dated ordeal.

The new Planet of the Apes series

The original "Planet of the Apes" movies began with the concept of a simian-conquered world, revealed in one of cinema's most famous twist endings. However, despite an excellent start to the series, with a screenplay courtesy of "The Twilight Zone" creator Rod Serling, subsequent films were weaker, rushed cash-ins (and we're not even going to breathe a word about Tim Burton's 2001 abomination).

The 21st-century remake, which features four films to date — "Rise of the Planet of the Apes," "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes," "War for the Planet of the Apes," and "Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes" — met far greater critical acclaim. Where the original series jumped backwards in time to bring its protagonists to the modern day, the remakes tell a more conventional narrative, following an evolved chimpanzee named Caesar and his ongoing and increasingly bloody struggle for freedom.

Unlike the warlike and aggressive apes of the original, here the anthropoids are portrayed as sympathetic. With some notable exceptions, it's the humans who are the villains. Andy Serkis and his fellow actors' motion capture work are the stars of this show, making for completely convincing CGI heroes.

Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn

"Evil Dead 2" is not officially a remake, but it might as well be (lead actor Bruce Campbell has, in the past, referred to it as a "requel"). Granted ten times the budget thanks to the success of the first film, director and writer Sam Raimi essentially had the opportunity to make his movie all over again — and to make it bigger, better, and closer to the vision he had in his head.

Ash is a non-descript character in the first film, but the sequel — sorry, requel — fleshes him out, making him more like the wisecracking, sardonic antihero we know him as today. "Evil Dead 2" resembles a superhero origin story in that regard, although a chainsaw-hand is an admittedly weird superpower.

"Evil Dead 2" is also a more confident film than its predecessor, as Raimi had picked up — and mastered — some new tricks in the 6 years since the release of "Evil Dead." The thoroughly unpleasant tree molestation scene from the original is thankfully gone, evidence of a less childishly gratuitous direction for the series. "The Evil Dead 2" also introduced humor and slapstick to the franchise, a direction that Raimi would push even further in 1992's fully-fledged sequel, "Army of Darkness" (working title "Medieval Dead").

True Grit

Whether you prefer the original "True Grit" or the Coen brothers' remake comes down to how you feel about the legend that is John Wayne. The original 1969 film is one movie in which the man's larger-than-life persona works against him. In the first movie, Rooster Cogburn, former U.S. Marshall, always feels like John Wayne, not a character in his own right. It's an excellent film and a worthy Oscar-winner, but the 2011 remake has the edge.

"True Grit" is an unusually restrained movie from the Coens, with few of their typical eccentricities. It's not only a better-looking movie than the original, but it's also closer to the Charles Portis source material — Jeff Bridge's Rooster is less warm and endearing than Wayne's, and the film's general mood is darker and more violent. Still, all told, this is the closest fight of any of the movies on this list.