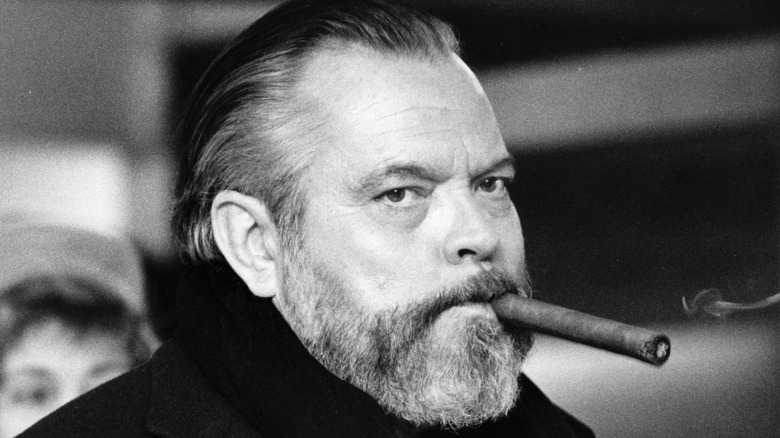

The 10 Best Orson Welles Characters Ranked

Before he gained a reputation of being difficult to work with and decamped to Europe twice in search of more freedom as a filmmaker, Orson Welles was a former child prodigy who was initially embraced by Hollywood as a wunderkind. Welles directed himself to critical acclaim in starring screen roles as both "Macbeth" and "Othello" and sparked a Halloween-eve panic in 1938 with his radio adaptation of H.G. Wells' "The War of the Worlds." His 1941 epic "Citizen Kane" routinely tops lists of the best films of all time, including those of the American Film Institute, even though he made it when he was only 25 years old.

From the masters of the world to the mere players upon its stage, Welles was able to make a broad spectrum of characters his own. But with a personality as outsized as his waistline, which of the characters that Orson Welles played were most ideally suited to his talents? Here, in our minds, are his 10 best.

10. Mr. Charles Clay — The Immortal Story

Welles' adaptation of Karen Blixen's short story is both his briefest film, at 60 minutes, and the first film he shot in color. While Mr. Clay, Welles' wealthy merchant character, is in no way sympathetic, his story is still tragic, because he clearly yearns for something beyond the confines of the life that he's chosen, even though his self-imposed limits won't allow him to seek it out.

In "The Immortal Story," Clay believes that stories should only be told about things that have actually happened, so he arranges to have an old mariner's tale about a rich old man who pays a poor young sailor to impregnate his beautiful wife made real. Clay is unmarried, so the woman he recruits to play his wife, Virginie, is the daughter of a former business partner, Louis Ducrot, whom Clay ruined financially to the point that the man committed suicide. Clay reveals he was motivated to destroy Ducrot because he was afraid to feel friendship for his business partner, thinking it would make him weak.

Given Welles' subsequent portrayal of a powerful film director seeking to possess the handsome young lead's sexuality in Welles' posthumously released "The Other Side of the Wind," it's not out of bounds to read a gay subtext into Clay's admission. Even without it, though, Clay's fears regarding vulnerability and closeness make him his own jailer, trapped in a gilded cage of his own making.

9. Gregory Arkadin — Mr. Arkadin

The fact that "Mr. Arkadin" was a mess of a film upon its initial release, with multiple edits released over the course of Welles' lifetime, only furthers the enigmatic allure of its already fascinating title character, the regal and well-connected Gregory Arkadin. By depicting Arkadin as constantly throwing parties in opulent settings and seeking to protect his daughter Raina from the rougher elements of the social circles within which he himself travels, Welles' Russian magnate draws in equal measure from the Prosperos of William Shakespeare's "The Tempest" and Edgar Allan Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death."

Arkadin hires a small-time smuggler and ne'er-do-well named Guy Van Stratten to conduct what would today be called "opposition research" on himself, after claiming that amnesia had robbed him of his memories prior to 1927. Van Stratten ultimately figures out that Arkadin is only pursuing his past in order to bury it permanently, along with anyone who could talk about it.

Seeing an always-on-the-make con artist like Van Stratten realize he's been out-maneuvered by Arkadin makes one appreciate the skill that the older man hides behind his expansively gregarious public persona. In turn, that makes him all the more fearsome, even when he admits that affectations such as his thick beard are intended to frighten.

8. Jonathan Wilk — Compulsion

When it comes to fictionalized portrayals of real-life attorney Clarence Darrow, everyone wants to play Henry Drummond in "Inherit the Wind." I doubt any middle school classroom has ever staged "Compulsion" as a play. "Inherit the Wind" showcases Darrow at his most morally unambiguous, when he was ostensibly defending scientific discovery in the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial (which in turn serves as a stand-in for the McCarthy trials, which were contemporary to when the play premiered in 1955). But in "Compulsion," Welles' Jonathan Wilk is a fictionalized Darrow at his least popular, when he agreed to serve as the defense attorney in the 1924 Leopold and Loeb murder trial.

What made Darrow's defense so remarkable, and what Welles had to recreate in his performance as Wilk, was that he successfully pleaded for mercy on behalf of a self-confessed and unrepentant pair of killers. The murderers had been born with all the privilege in the world, then killed a defenseless child just to prove they could. Bradford Dillman and Dean Stockwell are so effective at making their fictionalized stand-ins for Leopold and Loeb contemptible that it makes Welles' delivery of Wilk's closing argument all the more powerful, but even before Welles advocates Wilk's (and Darrow's) belief that executions only beget further murders, we see the weariness in his character's eyes.

Welles' Wilk is tired because he understands from the start how monstrous his rich and remorseless young clients are. He receives no gratitude from them, nor does he expect any, for pleading their death sentences down to life in prison. As Welles plays him, Wilk is no roaring lion in the courtroom. He rarely even raises his voice, because he's not bullying. Instead, he's begging society to be better than the monsters it seeks to punish.

7. Harry Lime —The Third Man

As much as fans of Travis Bickle in "Taxi Driver" and Tyler Durden in "Fight Club" have been criticized on this count, the chipper, sociopathic Harry Lime was arguably part of the original "You missed the point by idolizing them" starter pack. As Lime, Orson Welles so thoroughly charmed those who saw "The Third Man" that the character received his own year-long 52-episode radio serial, "The Adventures of Harry Lime," in the United Kingdom, even though the character died in his debut film outing.

As much as it's easy to see why the earnest, curious Holly Martins (played by Welles' frequent collaborator, Joseph Cotten) would befriend the casually confident Harry Lime, we and Holly soon realize that Harry's untroubled smirk stems from a ruthless disregard for human life. And yet, even on Vienna's Wiener Riesenrad Ferris wheel, when Harry scolds Holly for caring so much about the plight of the "dots" on the ground, Harry is never as unaffected or indifferent as he wishes to appear.

The look of cold calculation that crosses Harry's face when his mask of frivolity slips as he susses out what Holly intends to do next attests to his cockroach-like tenacity. You don't survive while pulling as many scams as Harry Lime unless you're highly skilled at playing the odds. In addition to establishing that "The Adventures of Harry Lime" was a prequel to "The Third Man," the radio series also toned down its protagonist's roguishness considerably. Still, as Lime proves, Welles' innate charisma made even his scoundrels hard to resist.

6. Police Capt. Hank Quinlan — Touch of Evil

If you asked someone to draw a caricature of the words "dirty cop," odds are you'd get a sketch that looked like Hank Quinlan. From the moment that Welles first slouches out of the shadows as Quinlan in "Touch of Evil," he fits every clichéd description of a corrupt officer of the law. He's fat, even fatter than Welles was in real life at the time. His suits are ill-fitting and sloppily put together. His sagging jowls are coated with stubble, and even though we're told he's been sober for 12 years, his squinty eyes swim drunkenly.

Quinlan's deeds live up to his disreputable appearance, as we learn he's routinely planted evidence on suspects for years. Couple this with his none-too-thinly-veiled racism against Mexicans — never a great trait for an American police captain in a border town — and Mexican special prosecutor Miguel Vargas' crusade to expose Hank Quinlan's corruption seems entirely warranted, even before Quinlan frames Vargas' wife for drug use and murder.

And yet, what separates Quinlan from any number of other onscreen "bad cops" are the hints he was once better than this. He couldn't bring his wife's killer to justice as a rookie cop, and the proof of his dozen years of sobriety lies in the double-chins he's picked up since by substituting candy bars for alcohol. Even the suspect that Vargas catches Quinlan framing for the bombing at the start of the film turns out to be guilty, because as Quinlan's acquaintances observe after his death, he was "a great detective," but "a lousy cop." As much as Quinlan authors his own fate, it's still haunting when he asks his ex-lover Tanya to read his future, and she says, "You haven't got any."

5. Professor Charles Rankin, né Franz Kindler — The Stranger

One disadvantage of the distance of history is that modern audiences might not realize how radical "The Stranger" was upon its release. As film director and historian Bret Wood noted on the audio commentary for "The Stranger," in the 1940s, "a large percentage of the population could not believe that the Nazi death camps were real." Only a year after World War II, "The Stranger" became the first commercial film to use documentary footage from the Nazi concentration camps.

Likewise, while having the character of fugitive Nazi war criminal Franz Kindler adopt the cover identity of the affably genteel prep school teacher Charles Rankin might not seem transgressive in and of itself today, it was harrowing at the time for suggesting that such profound evil could exist in our midst, without us noticing. Rankin is the perfect neighbor, with the perfect pedigree. He's greeted warmly by students in his small New England town, where he's engaged to the daughter of a Supreme Court justice, and he contributes to the community by helping to repair the town's 400-year-old clock tower.

Initially, Rankin says and does all the right things, but there's an undercurrent to his remarks on the German culture that the United Nations' Nazi hunter (Edward G. Robinson, cast strongly against his gangster type) picks up on. When one of Kindler's former associates arrives in town to beg him to confess to his crimes, the threads of Charles Rankin's carefully constructed identity slowly start to unravel. Kindler's self-assured, even eager, predictions of "another war" after he's been found out are all too relevant in light of certain resurgent political movements.

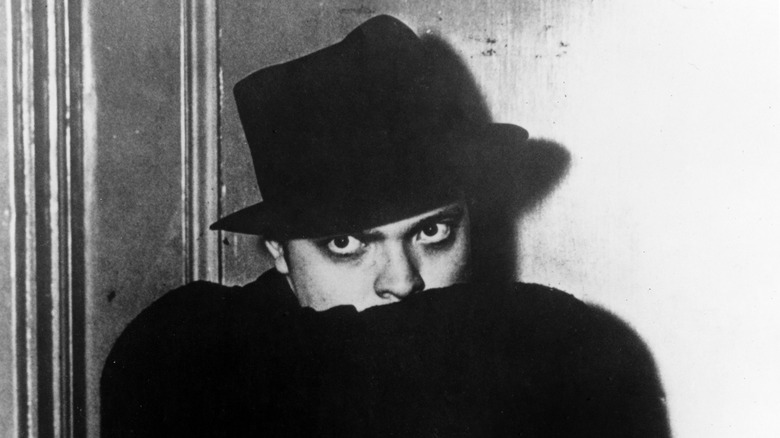

4. The Shadow

Although the Shadow made his broadcast debut as the ongoing host of a radio adaptation of "Detective Story Magazine" and was then adapted back into print with the first issue of "The Shadow Magazine" in 1931, it wasn't until the character proved popular on the page that the character received his own radio drama, which began in 1937.

By that time, the Shadow had assumed several "secret identities" in print, but the radio show cemented his "true" identity as a "wealthy young man-about-town" named Lamont Cranston. Cranston's socialite girlfriend, Margo Lane, was created for the radio. In the show's first 52 episodes, which aired from the Septembers of 1937 through 1938, Orson Welles played the title role, with his future "Citizen Kane" co-star Agnes Moorehead voicing Margo Lane in the first 26. Over the course of the following 18 seasons, the Shadow was played by six other actors, only two of whom logged more episodes in the title role than Welles.

As "The Shadow," Welles' voice was sonorous, sibilant and slightly nasal, drawing its strength and sinister qualities from its hushed undertones. Still, even when Welles played the Shadow, his signature line — "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?" — was spoken by Frank Readick Jr., who had voiced the Shadow for a number of the radio anthologies that the character hosted from 1930 to 1935.

3. Sir John "Jack" Falstaff — Chimes at Midnight

Orson Welles did not create Falstaff. William Shakespeare did. But much as Tom Stoppard drew from Shakespeare's "Hamlet" to create "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" in 1966, Welles drew from no less than five of Shakespeare's plays to create "Chimes at Midnight," starring the supporting character of Sir John Falstaff, whom Welles proclaimed "Shakespeare's greatest creation."

Welles plays Falstaff as a vain yet slovenly glutton, so fat that even the overweight actor required extra padding in his costume to play him. While Falstaff betrays himself as both cowardly and self-aggrandizing, he's nonetheless a mostly harmless and well-meaning ruffian, stuck in the rut of what might be called "arrested development" or "extended adolescence" today. Young Prince Hal recognizes Falstaff's role as a "misleader of youth," but the future ruler embraces the drunken old knight as a surrogate uncle, until Hal's father, Henry IV, falls ill, and Hal dutifully does away with his childish things upon his own crowning as Henry V. Just as growing up means Christopher Robin must bid farewell to the Hundred Acre Wood, so does becoming "a good and noble king" mean Hal must forswear his former lifestyle and banish Falstaff, who dies of a broken heart, even as he takes pride in Hal's newfound maturity.

Welles never missed a chance to evangelize Shakespeare to the masses. In a 1968 episode of "The Dean Martin Show," he conducted a nearly-seven-minute clinic on how to play Falstaff, donning the character's makeup and costume padding and reciting Falstaff's tribute to his favorite libation, sherry. Only Orson could have pointed out that Shakespeare did "commercials," or that Falstaff was "a swinger" and "the great-great-grandfather of all the flower children."

2. Charles Foster Kane — Citizen Kane

So many words have already been written about one of the greatest works of cinema in history that I can't hope to rival them, but what makes the title character of "Citizen Kane" so compelling is that he began as an attack on one of the world's most powerful men, only to become an accidental biographical portrait of the man who played him.

While screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz's original outline for the film was based on the life of newspaper publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst, the subsequent screenplay came to include elements that paralleled Welles' life instead. For example, Kane's separation from both parents during his early childhood echoed the deaths of Orson's parents by the time he was 15. And just as Charles Foster Kane ascended to the status of a titan of industry when he was barely more than a schoolboy, Welles was awarded an unprecedented contract to write, produce, direct, and perform in two films for RKO Pictures in 1939, when he was only 24 years old.

Although Hearst sought to derail Welles' career as revenge for "Citizen Kane," it proved to be a Pyrrhic victory for both men, since it wasn't until David Nasaw published "The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst" in 2000 that film critic David Thomson wrote in The New York Times of Hearst "at last emerging from behind the dazzling light of Charles Foster Kane," while Welles' need for creative control left him as friendless at the film studios of Hollywood as the elder Kane was at his palatial Xanadu estate. Like the intermingled ruins of twin Ozymandiases, the fused character of Charles Foster Kane serves as a monument to the hubris of two masters of mass communication.

1. Orson Welles — Himself

In later years, if you cast Orson Welles in your production — whether that was as a distinguished narrator (for Mel Brooks' "History of the World, Part I," or an episode of the network TV romcom "Moonlighting"), in a bit part (as Tom Selleck's boss, Robin Masters, in "Magnum, P.I." or the world-devouring planet Unicron in "The Transformers: The Movie"), or as a pitchman for frozen peas or Paul Masson wine – you wanted him to be Orson Welles, rather than playing another character.

Like Marvel Comics' Stan Lee, Welles' greatest creation was himself. Nowhere was this better showcased than Welles' 1973 quasi-documentary, "F For Fake," which concerns art forgers, celebrity biography hoaxers, and all-around con artists, but which frequently drifts into digressions about Orson's own life. The big man asserts the absurdity of assigning authorship to the Chartres Cathedral in France, while also contemplating the fleeting mortality of humanity, and recalls how he landed one his earliest acting gigs in Ireland by falsely claiming to have already achieved stardom in America. He observes, only half-jokingly, "I started at the top, and have been working my way down ever since."

A sleight-of-hand magician since his childhood, Welles delights in misleading his audience, promising them at one point to tell the truth for the next hour, before eventually informing them that hour had passed a while ago, and "for the past 17 minutes, I've been lying my head off." Regardless of how true any of his colorful anecdotes might be, Orson makes his disjointed docudrama feel like a pleasantly meandering dinner table discourse. By the end, your only regret is wishing you could have had more time to spend with the man.