Horror Movies To Watch If You Loved The Invisible Man

In ways both great and unfortunate, Leigh Whannell's "The Invisible Man" was a perfect pre-COVID-19 watch. Its protagonist, the indelible Cecilia Kass (Elizabeth Moss), is tormented by a camouflaged evil — one that infiltrates and corrupts every inch of the house she occupies, rendering her normal life meaningless. But the illness that Kass' ex, Adrian Griffin (Oliver Taylor-Cohen), represents is less pathogen than pathological; he is a gaslighter with psychotic tendencies, a man whose brilliance only bolsters his toxic, controlling impulses. He is any woman's worst nightmare, and is more frightening for how fully the toxic masculinity he represents permeates every facet of our society. During the pandemic, many Cecilias become trapped indoors with Adrians. The irony is stifling.

If this makes it sound like "The Invisible Man" is a difficult watch, good news: "The Invisible Man" is a film that appeals to horror fans and detractors alike because lies — not creatures, gore, or jump scares — are the primary currency of its terror. The film's most frightening moments hinge on convincing fictions and multi-layered betrayals. No sooner does Cecilia escape Adrian's clutches than her sister, her employer, and the police turn against her. During a year in which the facts surrounding a deadly plague were routinely called into question, these plot points should make "The Invisible Man" upsettingly appealing to almost any audience.

Here are 10 other films in which deceit, manipulation, and defamation feel frightening, stimulating, and all too relevant.

Gaslight

"Gaslight" creates the psychologically terrifying lexicon from which every other film on this list draws. "Gaslighting" — the practice of making someone slowly question their memories, their perception, and their sanity — takes its name from this film, which tells the story of a woman and her manipulative, abusive husband, and illustrates through both searing performances and subtle direction how diabolical planting a rogue thought in someone's head can be. If you somehow found your way to this article and haven't seen "Gaslight," the less I say the better.

I'll put it this way: if you want to loathe actor Charles Boyer; if you want horror-soaked noir; if you want to understand what it was like for many to live in America (and, by extension, the world) from 2016 to late 2020, then "Gaslight" isn't just the film for you — it's an essential human text. Stop reading and stream now.

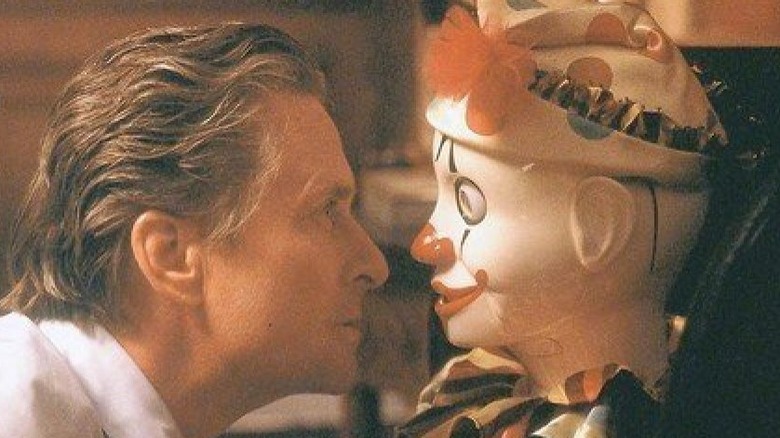

The Game

The most underrated picture on David Fincher's filmography, "The Game" is a suspense classic that posits that fiction may serve as both savior and Satan simultaneously. Over two-plus hours, "The Game" pushes its protagonist, the absurdly wealthy Nicholas Van Orton (Michael Douglas), past his psychological brink, all in the name of emotional healing. Before catharsis, though, comes creepy clowns, fake companies, and the queasiest use of Jefferson Airplane imaginable.

That might sound like a pulpy diversion and, in many ways, it is. "The Game," like "The Invisible Man," is compulsively watchable — it's a Hitchcock riff squarely made for the golden era of TNT reruns. But Fincher's third film also has heavy themes on its mind; specifically, what do you get the man who has everything? Van Orton has numbed his pain with money; his fears beget success. Like much of the 1%, he's as wealthy in self-delusion and dishonesty as he is in tangible funds. What does a person like that lack? Someone else's fiction.

Strangely enough for a film that has an open-ended conclusion, "The Game" is a thrilling testament to storytelling. The only way that Nicholas Van Orton can escape the prison he's built himself is through other narrators, ones that propel him through on-foot chases and car crashes towards cauterizing truth. Here, time doesn't heal wounds; haste does, in the form of a living page-turner. The power of fiction, indeed.

Swallow

Warning: if "The Invisible Man" left you even slightly queasy, avoid "Swallow" like the plague. Steer clear of it like the Mets do healthy pitchers. Like a bug heading towards electric lighting, turn away. Of course, that's easier said than done; like the Mets and many crispy insects, you will more than likely be drawn to this genre-free wonder, just like I was.

Why? Because, like "The Invisible Man," "Swallow" eviscerates domestic relationship norms and assumed trauma patterns, dragging its beleaguered housewife (an Oscar-worthy Haley Bennett) through the ringer before she arrives at an uneasy, well-earned peace. Her journey involves a frightening medical condition called pica, which drives people to eat non-food items, verbal abuse, and plenty of time unpacking the lies she told herself because others lied to, wronged, and sullied her. "Swallow" is the opposite of its title: a purge in which salvation proves sharp, be it through a tiny tack or the metaphoric blade of truth. In the best ways, it cuts deep.

Run

In "Run," lies, not charity, begin at home. While there are many projects in the Munchausen-syndrome-by-proxy subgenre, in which caretakers diagnose their young charges with made-up medical problems, Aneesh Chaganty's sophomore effort stands out from the pack thanks to its Spielberg-esque blend of rousing yet nail-biting setpieces. "The Invisible Man" made an ordinary home rife with dangers. "Run" says, "Hold my beer" to that. In its twisted world, getting from the bedroom to a bathroom becomes a matter of life or death. A staircase is Gremlins-level deadly. "Run" is a treat for anyone who grew up on Amblin Entertainment's '80s efforts or John Hughes' "Home Alone," creating an atmosphere that feels like a funhouse, but is far more horrifying.

"Run" wouldn't work, though, without the performances of Kiera Allen and Sarah Paulson, who arguably do career-best work. The fictions of a Munchausen-syndrome-by-proxy are only as believable as those who manifest them. In this case, that's all on Paulson and Allen, who briefly twist "Run" into a touching mother-daughter drama. That makes its savage ending — like the one in "The Invisible Man" — all the more satisfying.

Lucky

On its surface, "Lucky" has little in common with "The Invisible Man." For one, it's defiantly surrealist. For another, its assailant — a nameless man who attacks self-help author May (Brea Grant, also the movie's screenwriter) over and over, time loop-style — is almost defiantly visible, at least to his harried, overlooked victim. What makes Natasha Kermani's film a spiritual cousin to Leigh Whannell's thriller is its steadfast determination to reveal how all-consuming the cyclical violence and social lies perpetuated by the patriarchy really are. It does so spectacularly.

How spectacularly? Try an ending like "Birds Of Prey" on acid; try "The Truman Show," but with knives. "Lucky" owes many films a debt, but its examination of institutionalized misogyny is singular. And, like "The Invisible Man," "Lucky" proves its argument with biting dialogue, oppressive atmosphere, and often impeccable action. Give it the chance the film's male characters wouldn't.

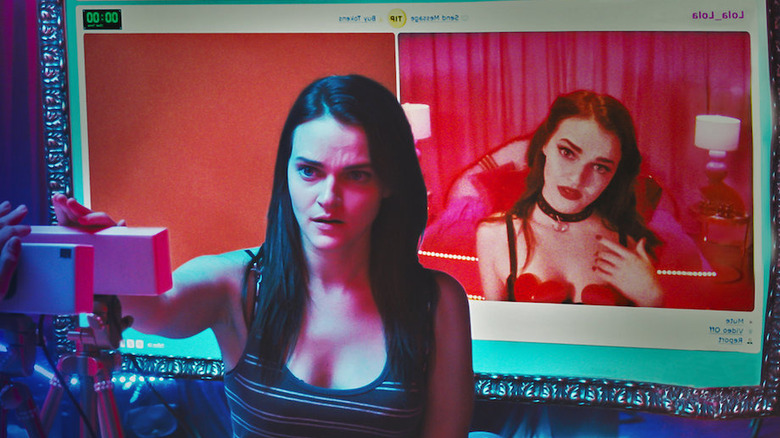

Cam

Full disclosure: "Cam" is one of my favorite films and I will not miss a chance to proclaim my love of it publicly. The first film from both writer Isa Mazzei and director Daniel Goldhaber features an enterprising cam girl named Lola (Madelinie Brewer) who discovers that her account has been taken over by a look-alike, robbing Lola of her identity and her sanity. Thus, it belongs in the same conversation as "The Invisible Man" and countless other horror greats.

Like the previously mentioned "Swallow," "Cam" is not for the faint of heart. It takes a look on the highs and lows of sex work; for some, the subject matter might be triggering. That said, the movie's empathetic portrayal of sex workers is both necessary and important, and those who related with Elizabeth Moss's infinitely resourceful Cecilia will adore Lola, if only for how brazenly Brewer realizes her on-screen.

Creep

"Creep" is usually classified as a found-footage horror movie; the designation is a cruel misnomer. And to be clear, I love found footage horror movies! For my money, "[REC]," "The Last Exorcism,, and "Gonjinam: Haunted Asylum" are some of the most fascinating, scary horror movies of this century. In each of those movies, a narrator is subjected, emotionally and visually, to an onslaught of evil, which we witness first-hand. The perspective is clear. That's what makes it frightening.

That's not so in "Creep." In Patrick Brice's underrated horror debut, monster and victim wrestle over the role of storyteller, controlling not only what we see, but how they're both perceived in the process. The characters are, in essence, fighting to speak their truth. The catch? Some of those truths are deadly. It begins when a videographer, Aaron (also Brice), is hired to record a video diary of a dying man named Josef (a stunning Mark Duplass), who wants to spill his heart, charmingly, onto the time capsule of celluloid.

What's captured instead, however, is not the living will Josef promised but a field guide to how human monsters survive and thrive in society. Like "The Invisible Man," "Creep" understands that a strong personality can conceal cruel intentions. Worse, charisma lets the forces of evil reframe their own twisted hero's journey. By the time "Creep" has finished, it's Josef's movie in full. We're just watching it, willingly, our perspective merged with his. That's a level of perspective-shifting found-footage films rarely touch, but "Creep" does, pure and simple.

The Invitation

Do lies take stronger hold in fragile spirits? That's the question at the heart of Karyn Kusama's spare but explosive "The Invitation," an ensemble piece in which a casual dinner quickly turns ominous. The film's central location shares a common architecture and geography with the waterside mansion of the first act of "The Invisible Man." Kusama, like Leigh Whannell, milks modern home decor's jagged edges and the shadows of California's rolling hills for every ounce of tension they're worth. Both portend violence.

But just as in "The Invisible Man," the bloodletting in "The Invitation" is far less interesting than the way it probes broken minds. There's Will (Logan Marshall-Green), still reeling from the trauma of his child's death. There's Eden (Tammy Blanchard), his suddenly-glowing ex. Most of all, there's Pruitt (John Carrol Lynch), a forthright party-crasher whose past catches up with every attendee. As Eden and her new husband, David, try to recruit their dinner guests into a cult, Will grows increasingly paranoid, spiraling out of control as he makes an erratic grasp for honesty. Perhaps that's what makes "The Invitation" so moving, as well as so scary. To be truthful and human, it posits, is to flail — gracefully, maybe; wildly, sure; but to flail, period? Absolutely. Life is too difficult to live through otherwise.

The Lodge

In 2020's "The Lodge," it's not just lies that are coldly, irrevocably terrifying. It's who you lie to. While Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala's follow-up to "Goodnight, Mommy" suffers from dreaded "second album syndrome" (it's full of repeated themes, similar set pieces, and so on), it sticks its landing thanks to an icy finish. In addition, it contains Riley Keough's top-tier performance, one that peels back layers of grief, fear, and violence with Elizabeth Moss-like elegance (between this, "The Girlfriend Experience," and "Zola," Keough has become the only positive argument for nepotism in Hollywood).

What makes "The Lodge" particularly upsetting — and interesting — however, is that little evil appears on screen. This is, without spoiling it, a film about the ways in which trauma begets trauma, and how we only see that when it's too late. A lesser movie would've pegged this thesis on a big bad; "The Lodge" is not a lesser movie.

The Rental

Dave Franco and horror are hardly synonymous. Though the 36-year old appeared (memorably!) in 2013's "Warm Bodies," his oeuvre has tended towards fiery comedies, in which he most often plays the calm within their storm. His performances are naturalistic — distressingly so. If Richard Donner made us believe a man could fly, then David Franco taught us that magicians know kung-fu, and also parkour.

The point is: Franco rarely strikes at horror's highs or lows. How fitting, then, that his directorial debut, "The Rental," doesn't either. Ostensibly a mumblecore relationship drama which collides head-on with a slasher flick, "The Rental," like "The Invisible Man," concerns itself with mining horror from toxic relationships. It's plot is built from stacks of interpersonal lies, the kind that failing couples often tell themselves. In "The Rental," those mistruths collapse during a weekend getaway plagued by with interpersonal tension, a shady Air B&B owner, and more loaded looks than you can shake a stick at. When the truth is finally revealed, the bodies start piling up. Franco, on brand, makes the carnage feel as normal as breathing.