Movies To Watch If You Loved Godzilla Vs. Kong

When Legendary Entertainment debuted its "MonsterVerse" with "Godzilla" in 2014, you stuck it out through the generic family drama and the two MUTOs for the promise of seeing the big G. You reveled in the "Apocalypse Now" Vietnam War-era vibes of "Kong: Skull Island" in 2017, and you basked in seeing titans like Mothra, Ghidorah, and (technically) Rodan tussle with "Godzilla: King of the Monsters" in 2019. Finally, 2021's "Godzilla vs. Kong" pitted king against king, as the MonsterVerse been teasing all along.

So, now what?

Maybe the MonsterVerse is your only experience with kaiju (Japanese for "strange beasts"), or maybe you have memories of a childhood spent watching decades-old giant monster movies, replayed on shows like "Elvira's Movie Macabre" or TBS' "Super Scary Saturday." Either way, if you loved "Godzilla vs. Kong," there are plenty of other fun films in the same vein to check out.

Fair warning, though: I will only briefly mention the 1969 animated short, "Bambi Meets Godzilla," which speaks for itself, and I will not be spotlighting the films of Rodan, who is 100% useless in everything that he does.

King Kong (1933)

There had been giant monster movies before "King Kong," such as the 1925 silent film "The Lost World," and there were many attempts to simply copy Kong's success, such as "Son of Kong" in 1933, the Japanese-produced "The King Kong That Appeared in Edo" in 1938, and "Mighty Joe Young" in 1949. But none of them combined a prehistoric setting with a titanic beast who could elicit equal measures of fear and sympathy from audiences as effectively as "King Kong."

"King Kong" was made in the '30s, back when discovering uncharted lands inhabited by dinosaurs and other oversized creatures still seemed possible. More importantly, the film gave us a monster whom we could root for enough that we didn't want him to be harmed, even as he was guaranteed to wreak enough havoc to make us cringe. Also, Kong's quasi-romantic bonds with various attractive human women over the years arguably set a precedent for other kaiju to develop more innocent psychic connections with adorably precocious children.

Godzilla (1954)

Superman fought an unfrozen dinosaur in the 1942 animated short "The Arctic Beast," while a nuclear bomb test north of the Arctic Circle awakened another dinosaur in the 1953 live-action film, "The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms," based on Ray Bradbury's 1951 short story, "The Fog Horn." But like Kong, Godzilla surpassed his predecessors by coming across as a tragic figure in spite of the tragedies he visited upon others, as a dinosaur forced to deal with a modern world he could neither comprehend nor reconcile himself with peaceably.

Rather than a comely blonde, Godzilla's connection to humanity was the Japanese scientist Daisuke Serizawa, who was left scarred, both mentally and physically, by World War II, and whose potential for devastation rivaled that of Godzilla — Serizawa's genius created the "Oxygen Destroyer," which had the capability to disintegrate Godzilla, but which Serizawa feared would be added to humanity's war-making arsenal alongside nuclear weapons.

Serizawa ultimately burned his notes and committed suicide while detonating the Oxygen Destroyer, convinced that neither he nor Godzilla could be allowed to exist.

King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

The original brawl-for-it-all was also the only big-screen match-up between the two titans prior to 2021's "Godzilla vs. Kong," and that it succeeded as much as it did owed more to its pitch-perfect high-concept premise than to its cinematic execution, which considerably lightened the tone of the Godzilla films moving forward.

"Godzilla Raids Again" in 1955 had already done the heavy lift of introducing another member of the same species as Godzilla, but getting Kong to Japan involved a needless satirical subplot about a Japanese pharmaceutical company who wanted a giant monster to boost the ratings of the television shows it was sponsoring.

This belabored setup did have the dramatic benefit of making humanity responsible for the damage done by both battling beasts, while the fights themselves managed to be big dumb fun, employing a combination of actors wearing rubber suits and stop-motion animation, even if Kong's victory was marred by the film giving him electricity-based powers he never manifested before (or since).

Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964)

The popularity of "King Kong vs. Godzilla" led Toho Studios to pit the big G against Mothra for his following film, which doubled as the direct sequel to Mothra's well-received 1961 cinematic debut. Although it continued the previous film's theme of acquisitive corporations seeking to exploit nature via the proxy of the kaiju — in this case, one of Mothra's eggs — "Mothra vs. Godzilla" delivered a more deft level of social commentary than its predecessor.

While Godzilla acted as an agent of sternly unforgiving moral judgment, indirectly killing the film's greedy human villains, Mothra was cast as an emissary of peace, interceding on behalf of the human villagers who found her egg and shielding them from Godzilla's attacks. Just as 1961's "Mothra" chronicled the course of her life cycle — egg, caterpillar, cocoon, and butterfly — "Mothra vs. Godzilla" completed the process by having Mothra sacrifice her life to stop Godzilla before two larvae hatched from her egg to bind Godzilla in sprays of unyielding silk.

This cemented not only Mothra's status as the relatively benevolent queen of the kaiju, but also her Phoenix-like pattern of death and rebirth.

Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964)

Like Thanos in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, King Ghidorah was a villain forged in the fires of line-wide crossovers between other big-name characters. It's not for nothing that the original Japanese title for Ghidorah's cinematic debut literally translated to "Three Giant Monsters: Earth's Greatest Battle." The three giant monsters in question were Godzilla, Mothra, and yes, even Rodan, and astute viewers of 2019's "Godzilla: King of the Monsters" might note how much of its template was borrowed from "Earth's Greatest Battle."

This film revels in the ridiculousness of its era, from Mothra's miniature twin "fairy" priestesses to a prophetess from the planet Venus, as the three-on-one match-up between Earth's native kaiju and the outer-space invader Ghidorah crudely but cannily anticipated the dynamics that professional wrestling would adopt under Vince McMahon's management in the '80s.

And while Mothra led the charge against Ghidorah, compelling an initially recalcitrant Godzilla and Rodan to rush to her aid after Ghidorah struck back, this film marks the turning point in Godzilla's transition from nature's aggrieved retribution against humanity into an admittedly begrudging defender of Earth.

Destroy All Monsters (1968)

If "Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster" was the kaiju equivalent of the MCU's "The Avengers," then "Destroy All Monsters" is "Avengers: Infinity War," featuring 11 kaiju, including not only Godzilla, Mothra, Rodan and Ghidorah, but also Anguirus from "Godzilla Raids Again," Baragon from 1965's "Frankenstein Conquers the World," Gorosaurus from 1967's "King Kong Escapes," and Minilla, a.k.a. Minya, the diminutive title character of 1967's "Son of Godzilla," plus a few seat-fillers no one has ever cared about.

The film was originally slated to include more monsters, among them King Kong, but budget constraints cut the number of monsters, and Toho's rights to Kong had expired by the start of production.

What "Destroy All Monsters" did deliver was unprecedented spectacle, as the United Nations Scientific Committee corralled the extended cast of kaiju onto what would later be named "Monster Island," from which they were then freed to attack the world's capitals by an alien race known as the Kilaaks. The final, literal king-of-the-mountain match between the Kilaak-allied King Ghidorah and all the other kaiju at Mount Fuji makes the whole film worthwhile.

Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975)

I was sorely tempted to slot 1974's "Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla" onto this list, since it debuted the original Mechagodzilla, revealed in that film as another weapon of would-be alien invaders, but its direct sequel, "Terror of Mechagodzilla," benefits from tighter pacing and the absence of its predecessor's musical break.

Just as "Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla" introduced the leonine kaiju King Caesar as a guardian deity and ally for Godzilla against Mechagodzilla, so did "Terror of Mechagodzilla" introduce the aquatic kaiju Titanosaurus as an ally for a rebuilt Mechagodzilla, as the aliens who created Mechagodzilla teamed up with Dr. Shinzô Mafune, the mad scientist who discovered and acquired control over Titanosaurus.

While "Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla" playfully equipped its robotic doppelganger for the big G with a veritable Swiss Army knife-style arsenal of launching missile fingers, laser-shooting eyes, and a forcefield shield, "Terror of Mechagodzilla" went a bit darker with its human drama, revealing that Mafune's daughter, Katsura, was transformed into a cyborg years before, but she ultimately retains her humanity by sacrificing herself to discontinue the aliens' control over Mechagodzilla.

Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989)

By this point in the film franchise, the Japanese were getting real tired of Godzilla treating Tokyo like Rick James treated Eddie Murphy's couch, so the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) decided to try and weaponize some of the Godzilla cells they'd harvested from the monster, only for the American "Bio-Major" scientific corporation to threaten terrorist attacks unless those cells were turned over to them instead.

Meanwhile, Dr. Genshiro Shiragami lost his daughter, Erika, when their attempt to merge Godzilla cells with genetically modified plants was bombed by Bio-Major agents. When Shiragami merged Erika's cells with those of a rose to try and preserve her soul (as grieving parents are wont to do), it must have made perfect sense to add Godzilla cells into the mix as well.

What's bizarre is how much this seeming dream-logic makes sense within the context of the story, which was animated by earnest concerns over the ethics of genetic engineering, and illustrated via a succession of visually compelling, David Cronenberg-esque evolutionary transformations for Biollante, who eventually accomplished the nigh-impossible feat of making Godzilla appear small by comparison.

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995)

It was the end of an era — specifically, the Heisei era of Godzilla films, which started when Toho rebooted the series with 1984's "The Return of Godzilla," a direct sequel to the original 1954 "Godzilla." In this iteration, Godzilla went out with a literal bang.

This time, the JSDF were forced to try and save a smoldering Godzilla when they determined that his heart, which amounted to a biological nuclear reactor, was undergoing a nuclear meltdown that threatened to light the Earth's atmosphere on fire. Meanwhile, the lingering effects of Dr. Serizawa's Oxygen Destroyer had awakened and, over the course of four decades, gradually mutated a formerly dormant colony of prehistoric crustaceans in Tokyo Bay, which eventually merged into the flying kaiju Destoroyah.

The glowing, lava-like rashes covering Godzilla's body underscored how much he was hurting, while Little Godzilla, aka Godzilla Junior, the no-less-cloying second son of Godzilla, finally distinguished himself as a proper inheritor of the title. Although the JSDF narrowly averted the Earth's destruction, neither Tokyo nor the original Godzilla notched a happy ending out of the deal.

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001)

Another direct sequel to 1954's "Godzilla" that ignored all the previous installments, "GMK" (as it's known by fans) adopted horror novelist Garth Marenghi's stance that subtext is for cowards by establishing that Godzilla was animated by the spirits of those who were killed in the Asian-Pacific theater of World War II.

As Godzilla lashed out at Japan for denying its war crimes, Mothra was aided in her usual duties as a defender of humanity by the unlikely allies of Baragon and King Ghidorah, with the three recast as "Guardian Monsters" of ancient legend.

The miniature models for the Yokohama city set in "GMK" appeared again in Quentin Tarantino's "Kill Bill: Volume 1" in 2003, that time standing in for Tokyo instead, after "GMK" art director Toshio Miike supplied them to Tarantino. Also, when a JSDF admiral told his troops about the events of both 1954's "Godzilla" and the American-made "Godzilla" of 1998, referring to "a monster similar to Godzilla," who "ravaged New York at the end of the last century," the line drew laughter and cheers from Japanese audiences.

Godzilla: Final Wars (2004)

For the final film of the franchise's Millennium era, which began with "Godzilla 2000: Millennium" in 1999, and Godzilla's 50th anniversary, Toho Studios made like Gary Oldman in "Léon: The Professional," and demanded the presence of everyone. If "Destroy All Monsters" was the kaiju equivalent of "Avengers: Infinity War," then "Godzilla: Final Wars" was "Avengers: Endgame," beating its predecessor's head-count of 11 giant monsters by featuring 14 kaiju.

This list included not only A-listers Godzilla, Mothra, Rodan (we're being charitable here, folks), and an alien-allied (again) Ghidorah as "Monster X," but also familiar snarling faces Anguirus, Minilla, and King Caesar, as well as the "Destroy All Monsters" seat-fillers, Kumonga the spider and Manda the sea-serpent (the reptilian Varan was not invited, due to total lack of interest). "Final Wars" even scored previous "versus" luminaries Hedorah the Smog Monster, Kamacuras the Gimantis, Ebirah the lobster-like "Horror of the Deep," and the hook-handed, saw blade-spinning, frill-sporting cyborg Gigan (so cool).

But the least-honored guest everyone still remembers was "Zilla," the aforementioned American-redesigned Fauxzilla from 1998, who was annihilated in literally less than 20 seconds by the Japanese Godzilla's atomic breath.

The Host (2006)

Before Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho scored American attention and acclaim with the sci-fi societal critique "Snowpiercer" in 2013 and Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature Film with the black comedy-thriller "Parasite" in 2019, he beat 2008's "Cloverfield" to the punch in making a monster movie for the handheld video era.

For all its shaky camera work, "Cloverfield" remained self-consciously cinematic in teasing out the reveal of its towering, city street-bestriding beast as it lurked between the skyscrapers of New York at night, whereas the most shocking moments in "The Host" come from its ungainly amphibious creature just randomly appearing, without any dramatic build-up, in full public view during broad daylight.

In the first scene in which "The Host" shows up on land, plodding awkwardly along a paved riverbank already thronged with onlookers, its clearly unpracticed attempts at walking would almost be comical if it wasn't picking up such terrible speed and trampling or tearing apart all the people in its path. After decades of kaiju being depicted with the devastating grandeur of natural disasters, "The Host" delivers a big, dumb, clumsy animal, running on fear, anger, and instinct, too huge and powerful to be steered.

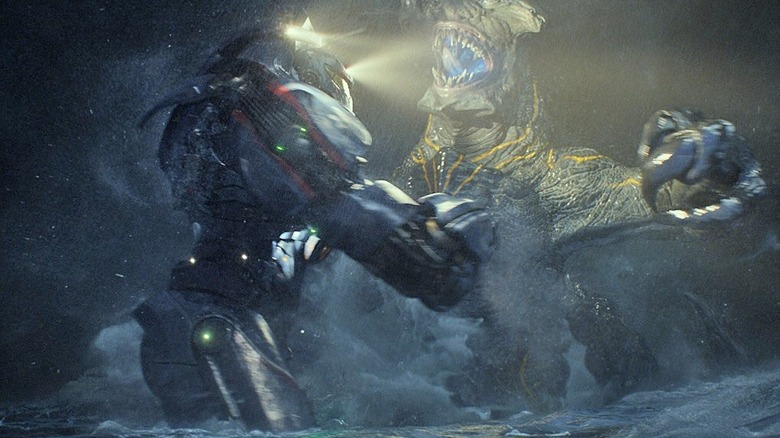

Pacific Rim (2013)

The beautiful verisimilitude of "Pacific Rim" was how it played like a faithful live-action adaptation of a cult-classic anime you'd never heard of before, only there was no one anime or manga series that served as its source material, because its mythos existed exclusively in the imagination of filmmaker Guillermo del Toro.

From "Voltron" to "Neon Genesis Evangelion," giant monsters trading blows with human-piloted robot-suits has been a premise that's proven its versatility and appeal, but del Toro still invested effort into selling the concept. That included assembling an all-star cast featuring Academy Award-nominee Rinko Kikuchi, "The Wire" star Idris Elba, former Hellboy Ron Perlman, and even Charlie Day from "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia."

Beyond its knock-down, drag-out fights, "Pacific Rim" explored the quirks of what a world regularly invaded by interdimensional kaiju might be like, while del Toro coated it all in a candy-apple sheen.

Shin Godzilla (2016)

When Toho rebooted the Godzilla franchise for the third time, it disregarded even the original 1954 "Godzilla" film, and yet, it also took the lessons of other monster movies to heart and incorporated their best innovations into "Shin Godzilla."

As Mothra's films had done from her debut forward, this blank slate of a Godzilla was shown undergoing a sequence of metamorphosis; different stages often left Godzilla as awkward in appearance and mobility as the star of "The Host." Like the glowing, smoldering Godzilla who'd fought Destoroyah, the "Shin" Godzilla's physical design conveyed how painful it was for him to contain so much destructive power, with raw red flesh exposed between the cracks of his burnt-looking scabrous skin. Beams of energy shot out of his body, not only through his atomic breath, but also his dorsal plates and the tip of his tail.

Also like "The Host," perhaps the most existentially terrifying aspect of "Shin Godzilla" was its all-too-realistic portrayal of how baffled and ineffective an overly bureaucratic government would be in responding to the immediacy and scale of such an emergency.

Gamera the Brave (2006)

Since his 1965 cinematic debut, the films of Gamera, the giant flying prehistoric turtle and "friend to all children," have been featured in no less than five episodes of "Mystery Science Theater 3000," no doubt due to being absurdly kid-friendly (complete with a cheery theme song). However, as amusing as they are, the human side of these stories still shines on through. While other kaiju are manifestations of science gone mad and the consequences of human hubris, or represent the indifference of nature to human concerns, Gamera has always been an invisible recess buddy.

That's never more true than in "Gamera the Brave." The last Gamera film to date unabashedly plagiarized "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" with a slice-of-life tale about a boy and his friends finding a doe-eyed baby turtle whose ability to perform seemingly magical feats, as well as his rapid rate of growth, soon draws the acquisitive attention of the government.

In both his battles with fellow amphibian kaiju Zedus and his escape from government captivity, Gamera remains an adorkable pudge-pot chump with an indefatigable underdog spirit. Even the most cynical viewer can't help but root for him.