20 Movies About Aliens That You Definitely Need To Watch

Films with aliens are rarely about the aliens themselves. These interstellar visitors usually serve as metaphors for human nature, a reflection of our politics, or a means to discuss strange natural phenomena. As Stephen King explained in "Danse Macabre," his non-fiction exploration of the horror genre, the things that frighten or confuse us change shape with each generation. The aliens of the '50s and '60s were Cold War relics that played on social paranoia. The aliens of the '80s reflected conspiracy theories and economic fears. Today, aliens represent ecological or transfigurative themes, embodying our worries about social unrest and the planet's future.

Although many movie aliens are created to talk about human problems, the aliens themselves often become memorable, too. The aliens in the movies listed here either bring out important details about ourselves or transcend the story and become special in their own right (and a few of them are just wicked cool to look at). To highlight some lesser known films, a few popular galactic visitors aren't listed (sorry, Predator!). But don't worry. Although these are 20 of the best, they're by no means the only alien movies fans should check out.

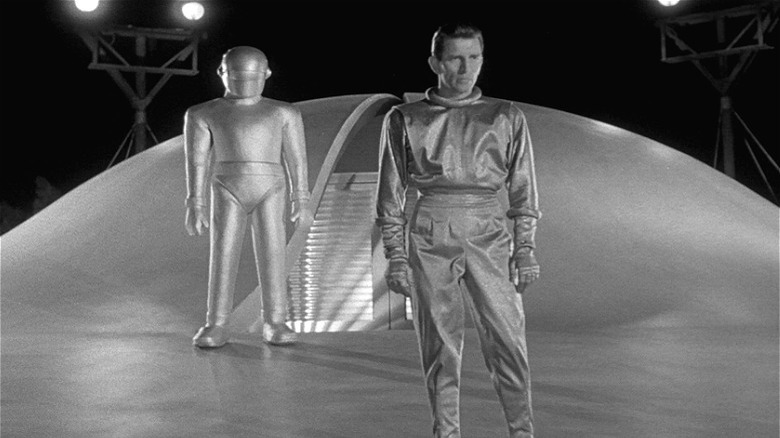

The Day the Earth Stood Still

With its deliberate pace and eerie emotional distance, "The Day the Earth Stood Still" remains a genre landmark. Michael Rennie's Klaatu is human aspiration incarnate, and brings with him his people's plea for Earth to be better, for humans to learn to be kind, and for us to move beyond our legacy of violence. Ironically, this plea is balanced by the threat of implacable force. While the plot suggests that Gort will only act to preserve peace, time has changed our perceptions. Today, it's hard to not see a metaphor for overenthusiastic US military intervention hiding behind Gort's robotic exterior.

At the time, "The Day the Earth Stood Still" and its alien motif served a stark warning about the risks of the nuclear arms race. It's still a compelling message, if overshadowed by a no longer subtle play on Christian spirituality, barely hidden in Klaatu's surprise return from the dead. It remains one of the finest examples of science fiction, and although Klaatu is too human to feel truly alien, his story still compels us to be our better selves.

The Thing

A remake of "The Thing from Another World," John Carpenter's 1982 classic "The Thing" delves into the question of what makes us human. As the alien itself proves, it isn't only about our will to live against all odds. The question of how far both species are willing to go to survive propels the movie through its last seconds, and thanks to the ambiguous ending, the answer will remain forever unclear.

The Thing's mimicry of humans is so good that when one character is assimilated offscreen, the only clue that it ever happened is the shocked reaction his body makes when he's treated for a heart attack: the Thing lashes out and kills the doctor trying to revive him. Yet, that perfection doesn't bring any comfort. In the end, "The Thing" suggests that we can't thrive as copies of ourselves; what makes us unique is our desire to be unique.

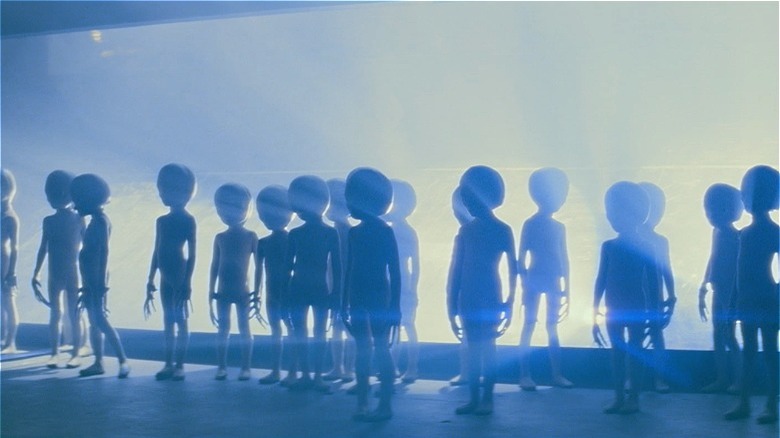

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Steven Spielberg made an odd trilogy of alien movies. In "E.T.," he explores the mysterious delights of childhood. In "The War of the Worlds," he explores family loyalties. But in "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," his adult protagonists abandon their loved ones for a chance to understand what lies beyond.

Not seen until the finale, the film's grey aliens work well as an obtuse metaphor for big questions about passing beyond the realm of human knowledge. It's not an allegory that Spielberg consciously intended. Today, he doubts he could create a protagonist that's capable of leaving his family the way Richard Dreyfuss' Roy Neary does. Yet, as gentle and as disruptive as these aliens are, they're also as implacable as those big mortal mysteries. When Neary leaves Earth, hand in hand with these fragile-looking beings, he glances back at the world he's leaving behind. But there's no regret in his face, just the childlike wonder of a man about to be reborn among the stars.

Communion

The only thing scarier than Christopher Walken's nightmares about alien abduction in "Communion" was being a kid and seeing its VHS cover art staring at you on a Blockbuster shelf. "Communion" was the flick that made the controversial grey alien phenomena mainstream. This adaptation of Whitley Streiber's allegedly true abduction experience wasn't a critical hit, but it remains the movie that spawned a subgenre of paranoia-fueled alien horror.

It's not recommended on its merits as a movie. There's a refusal on the part of "Communion" to take its premise seriously; only Walken's solid, unnerving performance sells its story at all. But the pop culture zeitgeist around aliens and their fascination with our bodies turns "Communion" into a safe glimpse inside that one should otherwise be carefully avoided. Streiber's credibility is secondary to what we can glean about the human mind from his dedication to his nightmarish story.

The Arrival

Not to be confused with a later entry on this list, 1996's "The Arrival" stars a Charlie Sheen still at the height of his health and talent, and pits him against the terrifyingly competent Ron Silver. Sheen plays a radio astronomer who intercepts an unusual transmission from a nearby star and is blackballed from his industry for revealing its extraterrestrial origins. From there, a tangled conspiracy drives him towards the truth: the aliens are already here, and the rapid shift in our planet's climate is meant to kill off humanity and create comfortable new digs for our new guests.

Directed by Peter Twohy, who would go on to create the Riddick franchise with Vin Diesel, "The Arrival" is surprisingly prescient with how it illustrates today's climate change fears. A niche topic of conversation at the time, relegated to Al Gore jokes and nervous but unheard scientists, these digitigrade alien mimics are almost comforting now. They suggest that our inevitable future can be controlled — and, in a way that's all too relatable, imply that someone else will have a good time on this planet at our expense.

Pacific Rim

The kaiju of "Pacific Rim" are the movie's main draw, with their unique designs giving each huge monster its own personality and behavior. They're delightful to look at, drawing out our secret desire to see them wreak havoc on Earth. Yet, in the film's context, each one is also a kind of organic Jaeger, acting at the behest of its own alien controller. We get a brief glimpse of these mysterious figures during the climax of the original film, as they look on with unreadable expressions as a Jaeger sacrifices itself to seal the Breach.

The film's artbook, "Man, Machine, & Monsters" provides a clearer look at these telepathic beings. The aliens behind the invading kaiju are spindly and eldritch, not quite bug-like, and covered in chitinous armor that looks like muscles flayed bare. Their motivations are roughly explained by a frantic, brain-fried Charlie Day as those of simple invaders, willing to clear out humanity by any means necessary in order to gather resources for their incomprehensible society. And that's all we know (we do not discuss the sequel in polite company)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

It's difficult for a remake to live up to the original, and it's still up for debate whether the 1978 remake of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" succeeds. The 1956 film is a haunting warning about post-war society, and the remake amplifies the paranoid threads of the original while leaning all the way into its dystopian premise. Both films use their vegan visitors as a metaphor for social divide and peer-pressured assimilation.

While both are effective films, the 1978 version's nihilistic terror and the visual horror of its assimilations take on extra poignancy today. "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" premiered shortly after the massacre of Jim Jones' Jonestown cult, and people who look just like us, but feel so distant as to be alien, carry that same sense of gloomy paranoia. Today's social divisions can feel insurmountable, and our political enemies take on a faceless, monolithic shape. We've swapped flowering pod people for coded emojis and memetic propaganda that brings in new devotees; as in these films, we spend each day worried that this isn't going to end well for all concerned.

They Live

"They Live" isn't a subtle film. There's not much to take away from an eight-minute, barely choreographed prizefight in an alley except a renewed admiration for the human spirit and a vague desire to watch some classic Rowdy Roddy Piper matches. John Carpenter's diatribe against Reaganomics is portrayed as a urine-tinted trickle-down on its transient blue-collar cast. They're hard workers who can't get a break, and the elites have consolidated all the power so efficiently that the American dream is exactly that — just a dream.

It's an old but accurate joke that "They Live" feels like a documentary about the hardships of the poor, except for the fact that Carpenter's upper-class villains have skinless alien heads and technology far past anything we're capable of. Our capitalist urges to consume and obey authority are amplified by brainwashing signals sent on certain visual signals. When watching "They Live," it's best not to think about the science too much. The aliens are the focus here, all too human with their lust for the glitzy scraps we churn out for their benefit.

The Brother from Another Planet

Afrofuturism as a word dates only back to 1993, but its concept of giving Black American imaginations a place to critique and explore the culture around them has been around for decades. While today's audiences have a wider variety of stories to explore, from "Lovecraft Country" to "Black Panther," a little-known film from 1984 touched on the emotional, nebulous, and very real damage done in the wake of the African diaspora. "The Brother from Another Planet" is anthological and loosely structured, but it's one of the first movies to use aliens as an allegory for the racial experience, a full decade after jazz genius Sun Ra used them to explore whitewashed capitalism.

The Brother's only alien traits are his three-toed feet, which he hides. Otherwise, he's a Black man with a gift for healing, stuck in New York City and hunted by two white men acting as the government's men in black. "The Brother from Another Planet" is a slow and lonely film whose silent protagonist serves as a blank slate for our racial stereotypes. Challenging that inherent racism, the Brother is unfailingly gentle and empathetic. Billed as a comedy, the movie's lonely alien is too innocent to withstand a cynical audience. It's better to come to this film with a mind as curious as his.

Interstella 5555

Anime rock opera isn't a genre that actually exists, but leave it to Daft Punk to make it feel like it's been around forever. Their lifetime love of animation legend Leiji Matsumoto was passionate enough to convince Matsumoto to direct "Interstella 5555," a companion film to the duo's "Discovery" album. The wordless story indicts soulless men in power who steal the ideas of beauty and creativity for profit. These concepts are the real aliens of the story. The villainous Darkwood doesn't understand what makes music special. He just wants the power it grants.

The physical aliens of "Interstella" are blue-skinned musicians happy to share their intergalactic tunes with any world with the ability to listen in. By the movie's second song, humans become the alien abductors, and the group is whisked off to Earth and forced into the grist mill of celebrity. It takes sacrifice to save them, and an indomitable spirit that fights for their freedom even beyond death. These are classic Matsumoto themes; he used transhumanism to discuss these same ideas in "Galaxy Express 999." From what we see of their culture, these aliens aren't much like us, but their music makes them family.

Contact

The aliens of 1997's "Contact" go unseen, unless we count the entity that takes on the shape of Dr. Arroway's deceased father. These aliens are a metaphor for the debate between faith and science, and the film makes it a point to blur that line as frequently as Carl Sagan's original novel. By the end of "Contact," there's little hard proof that Jodie Foster actually slipped through a wormhole and met a waiting messenger. But her emotional journey to get to that point allows her to take her experience on faith, and she's determined to make sure that we're ready for the next encounter.

Sagan's aliens are gentle but boilerplate. They're implied to be ancient, yet not old enough to be the ones who created the wormhole freeways. They understand that math is the universal language, and they're patient with younger races. The first step was making it this far. The next is up to us, affirming our theophilosophical need for free will, yet relying on our faith to continue.

Alien Nation

Mandy Patinkin is beloved across generations as Inigo Montoya from "The Princess Bride," but he also shined in an earlier cult hit. "Alien Nation" takes the racial tensions of "In the Heat of the Night" and transforms them into an allegory for immigration, too. The Newcomers, or Tenctonese, suddenly arrive on America's West coast, and their attempts to assimilate reveal that the deep cracks plastered over by our history are still very much with us.

The Newcomer society is different enough from ours to make understanding a crucial part of the film. There are some lighter elements, like the Newcomers' love of sour milk and their close-knit, religious families. But there is also a lot of heavy commentary. Many of the aliens were enslaved before their crash landing, and their former overseers have built the core of a new criminal underworld. It's a dynamic that's key to the film's big murder mystery, and was interesting enough to spawn a franchise that's still fondly remembered by many fans.

Starship Troopers

Paul Verhoeven is another director who doesn't waste time on subtle commentary. His anti-fascist satire, "Starship Troopers," bludgeons viewers in the face with his opinions within its first few minutes. Nominally an adaptation of Heinlein's novel, the movie picks apart the pro-military futurism Heinlein championed and uses it to create clear parallels with World War II. Heinlein's alien bugs become examples of "the other," enemies so safely inhuman that our ironic heroes can mow them down without guilt.

The movie is only shown from Earth's viewpoint, so it takes a while for the more subversive parts of the story to set in. The bug attack on Johnny Rico's anti-war homeland can be read as a false flag arranged by Johnny's pilot friend, acting on orders from intelligence. The recruitment ads shown in the film are borrowed from historical propaganda. But the most unsettling, yet subtle, moment of horror is when it is confirmed that a brain bug not only thinks, but feels. The bug fears humanity, a species that found a pretext for invading its world, and who considers the aliens as both disposable and unworthy of mercy.

10 Cloverfield Lane

Leaving aside the fact that the scariest moment in "10 Cloverfield Lane" is when John Goodman shaves off his beard, this movie's aliens are pretty spooky in their own right. Much of the movie hinges on whether they actually exist, or if Goodman's psychotic doomsday prepper zoomed around some final mental bend. But, as it turns out, they are real, and until its owner plunges deeper into madness, the bunker is the safest place to live.

"10 Cloverfield Lane" is a modern day "Twilight Zone" movie with a shaggy dog ending, but anyone who's ever fantasized about surviving an alien invasion has probably dreamed up a scenario a little like this one. The aliens themselves aren't featured much, yet they haunt the whole movie. They're biomechanical horrors, with tentacles spilling out of their low-altitude craft. These vessels are capable of chemical attacks that leave survivors with horrific lesions. It's not clear what they want, only that, by the end of the film, they're better than the human horrors Mary Elizabeth Winstead leaves behind.

Starman

"Starman" is the strangest and gentlest movie on John Carpenter's long resume, a sweet love story that fans of "The Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2" might find unusually relevant. But unlike that film's more cynical callbacks, this movie is a cozy first contact story built on comfortable tropes and given space to breathe.

Jeff Bridges always feels a little out of step with the fast tempo of celebrity society, and his role as the alien Starman plays to his famously befuddled yet cheery attitude. His attempts to mimic the people around him are jarring, but not as frightening as Karen Allen's reactions make them out to be. Starman is an anthropologist for his unseen alien race, and the quickness with which he adapts and empathizes with humanity proves he's a good one. The love that builds between Bridges' Starman and Allen's widowed Jenny is awkward and natural, and although its resolution relies a little too heavily on Christ metaphors, the earnest cast makes it work. "Starman" is an easily missed classic.

Arrival

Denis Villeneuve is doing for science fiction today what Ridley Scott did in the '70s. "Arrival," based on Ted Chiang's award-winning short story, is one of the few modern sci-fi flicks to introduce a truly alien species, and show the audience through how its characters connect with them on their terms. Almost too thoughtful for its own good, the film's fluid depiction of time and its reliance on detailed linguistic study can lose a viewer who doesn't want to commit their attention. But the reward is something that balances optimism and melancholy to create something special.

To these heptapod aliens, the key to understanding quantum time is encoded in their language, and unlocking how it works makes humanity one connected species. Both the catalyst for war but also the tool for stopping it, the heptapods' riddles also press on the necessity of free will. If we perceive time as they do — all at once — then our future is predetermined. Knowing that, would humans feel pressure to make the same decisions, or would we begin to crumble? "Arrival" doesn't offer an easy answer.

Dark City

The aliens of "Dark City" aren't benevolent, and they're not coy about what they're up to. Dark City's human residents are abductees, little more than cattle to be studied so that their overseers, the Strangers, can find a way to survive. The Strangers' true form is unsettling. They're parasites, jelly-like spiders that use human corpses as shells.

A group mind capable of some individuality, the Strangers will tear apart a human's sanity to find out what sparks our free will. With those answers, they hope to find a way to invigorate their dwindling species. But their meddling creates a backlash: By making their prisoners' minds similar to theirs, the Strangers create a human equipped with their own incomprehensible mental powers. There's an allegorical weight to these aliens; while Plato's Cave is a popular topic in film discussions, the Strangers might have benefitted from Nietzsche's knowledge. Gaze too long into the abyss of the human mind, and that abyss will gaze back into you.

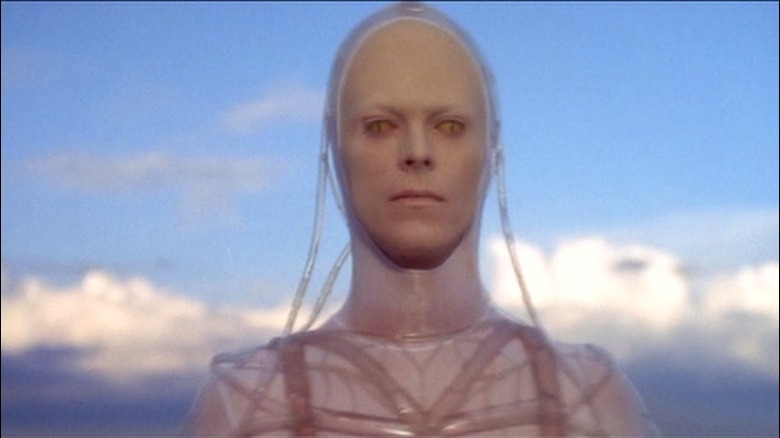

The Man Who Fell to Earth

Throughout his long and stellar career, David Bowie cultivated various stage personas, including the alien Ziggy Stardust and the eerie, distant figure of the Thin White Duke. It was this latter incarnation of Bowie's that provided the groundwork for Thomas Jerome Newton, the titular man who fell to Earth, who undergoes a slow but relentless spiritual implosion during Nicholas Roeg's cult sci-fi classic.

Newton is a gentler figure than Bowie's Duke. Humanoid enough to be familiar but still cattishly alien, he tearfully leaves his family behind to come to Earth in order to solve his world's drought. But, in one of the first big inversions of classic alien tropes, it's becoming too human that destroys Newton's chance to return home as a savior.

Lust and alcoholism befuddle Newton's intellect, pulling him deeper into human entanglements, until the government catches wind of what he is. Ironically, the tests meant to expose his alien nature trap him deeper in his human persona, as his contact lenses fuse with his golden, feline eyes. Bowie may have been one of the most perfect people to portray an alien, but Newton's failures and flaws made Bowie more human than ever, too.

District 9

Wikus van de Merwe is the most important character in "District 9," not because of what he goes through, but because of what he represents. He's an ordinary, if underwhelming, employee, a beloved husband, and a bit of a geek. But racism is so deeply ingrained inside of him that it's invisible to everyone except the prawn-like aliens relegated to a South African slum. Wilkus starts to care a tiny bit when he's forced to see Christopher Johnson and his son as individuals, but real empathy only blooms when his own transformation into an alien terrifies him into comprehension. Wikus could have been anyone. That's the point.

The aliens themselves are an unsubtle metaphor for human xenophobia, with real documentary footage used in Neil Blomkamp's short film "Alive in Joburg," on which "District 9" was based, to highlight the theme. But with Johnson as an ad hoc alien ambassador and secondary protagonist, he's granted a hero's thoughtfulness and resilience. The movie artfully flips our sympathies around, and we cheer when the human mercenaries start to drop. As for Wikus, he's still waiting for Johnson's promise to return to be fulfilled.

Annihilation

Jeff VanderMeer's "Southern Reach" trilogy takes the unearthly terror of Lovecraft and makes it into something both ecological and spiritual. Alex Garland's film adaption of "Annihilation," the first novel in the trilogy, is itself a half-remembered recompilation of the book's themes. Its aliens are never seen, only their creations and all that they imply. Both Garland and VanderMeer reject similarities to the seminal science fiction work "Roadside Picnic" and its adaptation, "Stalker," yet it's an unavoidable topic.

"Annihilation" tries to piece together the spreading effects of alien influence by what's been left behind. Even what that is isn't clear; it's a message meant for no one, so deeply fragmented it mixes with the DNA of every living thing it encounters. The Reach is slowly becoming subsumed by this alien influence, but the film asks what it does to our perception of humanity, and discusses our own drive towards self-destruction. The aliens become us by the end of the film, but what that means for our future is left uncertain.

"Annihilation" is a strange and dreamlike movie, and one of the most purely alien experiences put to film. It doesn't ask for understanding, nor does it help its audience interpret it. It's an unmissable movie, but also one that's not easily loved.