17 '80s Action Movies You Definitely Need To See

At the 1985 American Business Conference, President Ronald Reagan gunned down a tax increase by quoting Dirty Harry: "Go ahead — make my day." For better or worse, there are few more iconic intersections of age and genre than the '80s action movie. The PG-13 rating allowed for a whole new audience to enjoy wanton violence at the multiplex. Law enforcement came in units of two and spoke only in banter. Budgets, stunts, and physiques ballooned in alarming tandem. Less than a decade after he begged producers to let him be Rocky Balboa, Sylvester Stallone scored a record-breaking $12 million to play a professional arm-wrestler, more than double Harrison Ford's going rate at the time.

The excess was exceptional. "Die Hard." "Aliens." "The Road Warrior." "Conan the Barbarian." The '80s action pantheon is so ingrained, the players so much larger than life, that it's easy to overlook the rest of what the Reagan era had to offer. The following 17 films rarely appear among lists of the decade's finest, but they're no less essential to the kiss-kiss-bang-bang business.

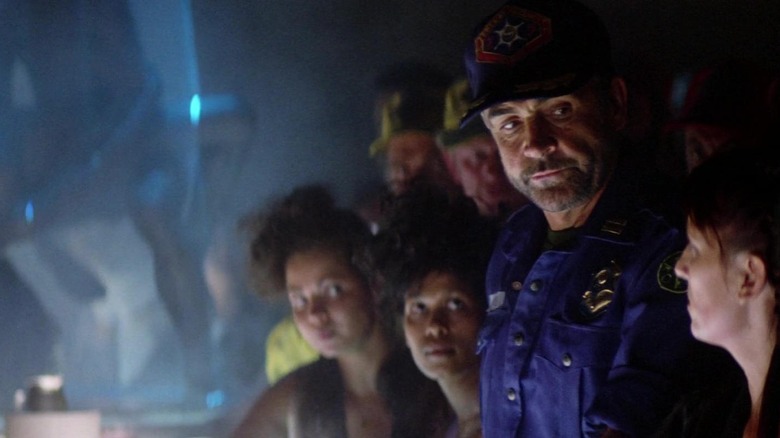

Outland

It's a sign of the times that writer-director Peter Hyams wanted to make a western and only got the greenlight after turning it into a significantly more expensive space western. Fortunately, as was the case with most of the decade's sci-fi, all the money is on the screen.

Living on the Io mining colony is like living inside a carburetor. Natural light is only a fond memory, somewhere on the list below intimacy and civilization. Workers sleep in floor-to-ceiling bunks, bodies arrive early at the morgue. Window or security office, the view never changes — stars, screens, and sirens all blink in the same abyss.

Costume designer John Mollo and composer Jerry Goldsmith were fresh off "Alien." The Ladd Company would co-produce "Blade Runner" the following year. That pedigree is unmistakable — "Outland" could exist in the same universe as "Alien" without even a rewrite. But what sets "Outland" apart is its retrograde grit. For all its lavish sets, death comes crude and rubbery. For all its day-after-tomorrow tech, the weapon of choice is a sawed-off shotgun. And for all its drawn-out family drama, Sean Connery is Sean Connery. It's "High Noon" in space, and the showdown does not disappoint.

No Way Out

"No Way Out" is a thriller and, early on, barely. Squeaky-clean sailor Kevin Costner meets beautiful stranger Sean Young at a political banquet. They lose their clothes immediately and hearts not long after. Only then does she reveal her other lover, Secretary of Defense Gene Hackman, who just so happens to be Costner's new boss. Before the two parties involved can come to a consensus, the testosterone runneth over.

Over the course of a single night, Costner's character finds himself framed as both a murderer and the intelligence community's Bigfoot — a Russian double agent embedded deep within the American government known only as "Yuri." The catch is, Costner is tasked with searching for "Yuri," and knows that Hackman's investigation will eventually find evidence leading to his arrest, but hasn't yet. Director Roger Donaldson sells the hook beautifully on the Blu-ray commentary: "Basically you've got a guy hunting for himself for a crime that he didn't commit."

The back nine of "No Way Out" is a frenzied race against a slow bullet. Costner, still a Tom Cruise contemporary and not yet Americana made flesh, sweats through the screen. He outruns cars, the combined might of Pentagon security, and a dot-matrix printer humming his death sentence in Morse code. The last 15 minutes are a masterclass in sustained tension, sucking out enough air to guarantee a gasp for the final surprise, whether or not it digests in memory. Fans of Donaldson's accidental action man should seek out some of his other films, "Sleeping Dogs" and "White Sands."

Black Moon Rising

"Black Moon Rising" was the first script that John Carpenter ever sold. It languished in development until his name started toplining posters. It appeared several times on this one, though Cameron didn't have anything to do with the belated production. Yet, even with the serial numbers filed off, his fingerprints are unmistakable.

Tommy Lee Jones plays Quint, a bone-dry master thief. He's a Snake Plissken prototype down to the cassette tape that the feds have enlisted him to steal. The world may not have ended yet, but Quint can already see the cloud and knows it's none of his business. He finally meets his match in Nina, the Cadillac of carjackers. Linda Hamilton, hot off "The Terminator," is all flint and shoulder pads. She makes the most of a role already doomed by obligatory romance.

But neither of them are the real star anyhow. The titular "Black Moon" was played by a one-of-a-kind prototype, the 1980 Wingho Concordia, and several stunt doubles. Parked, it looks like a lunch tray with wheels. At speed, it's a lunch tray with wheels and twin fireballs on the bumper. What does a jet-powered supercar have to do with a politically sensitive mixtape? Not much, but when each turn is a fishtail, all intimacy is scored by saxophone, and every air duct is Tommy Lee Jones-sized, who cares?

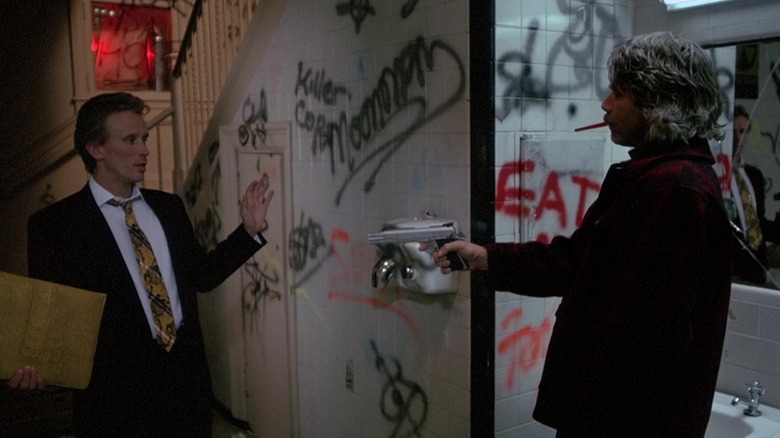

Shakedown

Peter Weller enters singing "Purple Haze" in a power suit, blending a morning cocktail of milk, orange juice, Maxwell instant coffee, and raw eggs. Sam Elliott wakes a little later in a Times Square movie theater, roused by the director's own z-grade action movies, and freshens up with sundries he hides in the bathroom fuse box. Detail for detail, these may be the greatest character introductions in buddy cop history.

The rest of "Shakedown" does not disappoint. Writer-director James Glickenhaus inflicts his would-be stereotypes — there wasn't much road left for the subgenre in 1988 — with refreshing complication. Weller is a formerly wide-eyed lawyer one wedding away from full-blown yuppiedom. Elliott is more boilermaker than man, but the only thing in the world he hates more than himself are his openly corrupt squad mates. Together, they hit the streets to become the do-gooders they always wanted to be.

"Shakedown" is the Goldilocks mean of absurdity — not too little, not too much, but just right. The dirty cops are played brutally straight, yet Elliott always offers to let his civilian pal use his gun while he drives. A tense foot chase across Coney Island ends with the Cyclone derailing into a hot dog stand. Its heart is in the right place, and there's no reason to let that get in the way of an eye-wateringly dangerous stunt.

Shoot to Kill

If Sidney Poitier hadn't ended his 11-year retirement from acting to star in it, "Shoot to Kill" might've fallen between the seats entirely. It's still a black hole by modern standards, unreleased on any home medium since 2003 and unavailable on all Disney-owned streaming services. A thriller this delicately crafted deserves better.

FBI agent Poitier reluctantly partners with mountain man Tom Berenger when his serial killer quarry makes a break for Canada across the northern Rockies. At first glance, this is a simple man-versus-nature story. But the suspect is hiking incognito with a group of hobbyists led by the mountain man's girlfriend, trail guide Kirstie Alley. As Poitier and Berenger take turns falling off cliffs and learning to respect one another, the audience gets to play "Ten Little Indians" with the character actor convention following Alley around.

Director Roger Spottiswoode keeps the performances from getting caught in the gears — Poitier silently scores the biggest laugh opposite a moose — and "Raging Bull" cinematographer Michael Chapman lets the picturesque danger speak for itself. Try not to flinch when a stuntman gets torqued at the end of a 100-foot climbing rope. "Shoot to Kill" may be chicken noodle soup for the pay cable soul, but this batch was made with love.

Raw Deal

When is an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie not an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie? The answer lies between "Commando" and "Predator" in "Raw Deal," the rare action vehicle that feels completely untailored to Arnold, enormous suits notwithstanding.

It's not so surprising, then, that he only starred in the film in hopes of winning the lead in producer Dino De Laurentiis' white whale project, "Total Recall." It didn't work, but the underwhelming box office made De Laurentiis sell those rights and the rest is history. "Raw Deal" is history, too, just not the kind that gets bronzed.

This is a latter-day Charles Bronson thriller about a no-nonsense cop going undercover in the Italian mob that just so happens to star an Austrian shaped like a Greek god. Beyond the request that his character not cheat on his wife, Schwarzenegger stepped in as-is. He chomps cigars, wins the boss' mistress, and pelts Robert Davi with the clunkiest one-liners of his career. The terminal inconsistency of it approaches high art. For every scene with Arnold compassionately handling his wife's alcoholism, there's another where he single-handedly destroys a casino while screaming about magnets. "Raw Deal" is the last non-Schwarzenegger Schwarzenegger movie and that's reason enough to savor it — the part where he drifts a convertible through a gravel pit gunning down hitmen and blasting "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" is just icing on the poorly baked cake.

Blue Thunder

"Blue Thunder" starts with a threat: "The hardware, weaponry and surveillance systems depicted in this film are real and in use in the United States today." What follows is an angry police-state screed only dulled into model-kit kitsch by a swarm of imitators.

Roy Scheider needed an iron-clad excuse not to make "Jaws 3D." He found one in this typically incendiary script from "Alien" scribe Dan O'Bannon. Frank Murphy has parlayed his Vietnam tour of duty into flying support helicopters for the police. Despite his lingering PTSD, he's chosen as a test pilot for a brand new crime-fighting machine codenamed "Blue Thunder." It takes him a while to look past its onboard microphones and thermal cameras and see the chopper for what it is: the end of civil liberty.

It's a startlingly subversive message for a decade of American action spent convincing audiences that cops can't go far enough to protect and serve. For all the Atari-class targeting systems and meticulously faked miniatures, this is a '70s conspiracy thriller at heart. Outside the cockpit, it looks like one, too. Director John Badham and "Chinatown" cinematographer John A. Alonzo leave Los Angeles dusky in the daylight and carve out the dark with the blue-green of supermarket fluorescents. The final showdown indulges a little too much in toy-vs-toy mayhem, but sometimes a mega-chopper is just a mega-chopper. This one's the gold standard.

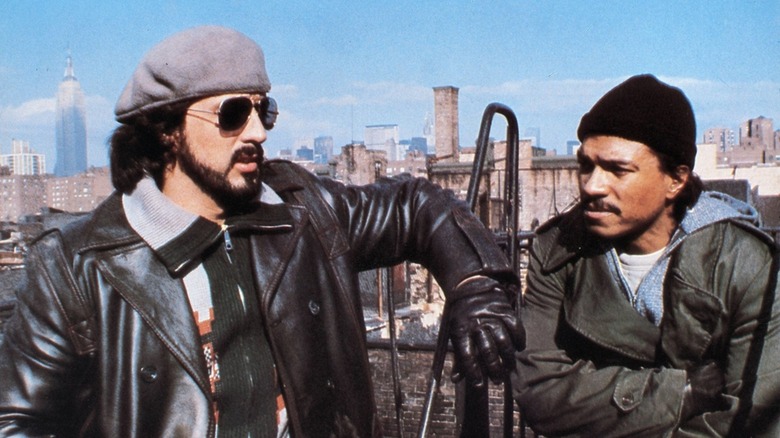

Nighthawks

As "Raw Deal" is to Schwarzenegger, "Nighthawks" is to Stallone, an odd-in-retrospect project made right before his image came fully into focus that also prominently features a Rolling Stones song.

Originally a draft for "French Connection III" that would've paired Gene Hackman's Popeye Doyle with a new partner played by Richard Pryor, "Nighthawks" kept the duo but dialed both personalities back. Stallone is taciturn to the point of disorder. There's hardly enough of partner Billy Dee Williams left in the final edit to measure. Production was famously torturous, with three different directors tagging in behind the camera and the New York State Supreme Court needing to rule whether or not the film could be completed.

It was enough to make big bad Rutger Hauer consider ditching American movies altogether. His frustration with the shoot and alleged loathing of Stallone makes "Nighthawks" legitimately dangerous. When he offers to cut Sly out of the sky, 275-feet above water in a stunt that left the star traumatized, it sounds like a vacation he's been putting off for too long. Outside the ring, Stallone lacked for villains worthy of his brawn, but here he's so obviously outclassed that the inevitable victory can't help but ring false. At least the journey is tense and grimy.

Action Jackson

There are few graver crimes in '80s action cinema than the failure to launch Carl Weathers, leading man. It took 12 years after Apollo Creed and fortuitous small talk on the set of "Predator" to win him his first star vehicle.

But what a vehicle it is. "Action Jackson" is Weathers' love letter to the Blaxploitation films that gave him his start, processed through the Joel Silver industrial complex. Lieutenant Jericho "Action" Jackson wears a badge like hurricanes wear beach umbrellas. He exists beyond the bounds of criminal justice and, when he's really mad, the laws of physics. The police chief, played by "Predator" alum Bill Duke, reprimands him for literally tearing a perp's arm off. Jackson musters no sympathy, considering he left the other one. Officer and evildoer alike speak of Jackson as downtown Detroit's closest thing to a campfire story — and they're not wrong.

It makes his adversary, martial artist Craig T. Nelson, that much sillier. Can the mighty Jackson be stopped by this marionette-legged businessman? Of course not. The real question of "Action Jackson" is how many flights of stairs he's prepared to climb in a lipstick-red Ferrari Testarossa for the privilege of kicking his butt. The answer may surprise you. It'll definitely delight you.

Sharky's Machine

Atlanta from above. Dawn, before anyone's awake, anything's alive. Lonely jazz and a lonelier voice, Randy Crawford, are already yearning for night again. The skyscrapers pass, up and away. All that's left is the rust-brown horizon and railroad tracks. Then comes Sharky, the first microscopic sign of life, and the full power of Doc Severinsen's brass — "Street Life," the way cinephiles remember it from "Jackie Brown."

Burt Reynolds has something to prove in "Sharky's Machine" and gets it out of the way with the very first shot. This isn't only his rebirth as a star, just six months after "Cannonball Run," but as a director. His self-proclaimed "Dirty Harry Goes to Atlanta" gives both Burts a chance to show off.

After a drug bust gone violently wrong, Tom Sharky is knocked down to vice squad, where he rallies a band of has-beens and never-weres into something like good guys. Together, the slightly unhinged team takes the fight to a mysterious pimp that seems to be running the entire city. The team is charming. The action is scrappy. The city is a vision in gauze and gravel, courtesy of "Bullitt" cinematographer William A. Fraker. The worst crime inspires Burt's best one-liner. The rest, his best work as a filmmaker.

Le Professionnel

Jean-Paul Belmondo arrives in monochrome, white replaced with Technicolor yellow, decades removed from his transcendently cool breakout in Truffaut's "Breathless." The youthful arrogance is still there in his face, but now etched where it used to be implied — during the stylized opening credits, wrinkles show black.

His closest thing we have to Belmondo, here 48-years-old and doing all his own stunts, in the modern age is the post-"Taken" Liam Neeson, but Belmondo lets himself have fun with his particular set of skills. Upon escaping the African prison where his country left him to rot, secret agent Joss Beaumont wastes no time completing his ill-fated mission and ruining every last bureaucrat that burned him. Even in a dead heat quick draw, he watches his prey with the bemused certainty of a man smuggling a joy buzzer instead of a .44 Magnum; he knows they'll all fall for it eventually.

The legendary Ennio Morricone is duly venerated for his contributions to the western, but "Le Professionnel" makes an overwhelming case for his criminal work with a single theme — "Chi Mai," a previously recorded melody specifically requested by Belmondo. It amplifies the slightest confrontation into the height of human tragedy and makes the mad spy's mission nothing less than a one-man death march. Converts should chase this with another Belmondo-Morricone actioner, 1983's "Le Marginal," a lesser film with bigger stunts.

Running Scared

In "Busting," Peter Hyams's first film, two 30-something cops consider retiring early. In "Running Scared," his ninth, Hyams finally lets them.

After nabbing Jimmy Smits, Chicago's most-wanted drug lord, best buds Billy Crystal and Gregory Hines earn a forced vacation for their own safety. Bolstered by inheritance from a fortuitously dead aunt, the pair decide to buy a Key West bar and call it quits. All they have to do before the paperwork clears is catch Smits again, freshly out on bail and vindictive as ever. Making the usual stakes grimly explicit — a Colombian necktie is threatened at one point — lends a unique weight to the gags; Crystal and Hines riffing sounds an awful lot like a distraction from their impending deaths.

Hyams had to fight MGM for his buddies of choice, but the pair is pure alchemy. Crystal and Hines play best friends first, police officers second, and end up forging one of the most believable relationships in the genre. The gunplay is best left to the director, here pulling his usual double duty as cinematographer, and he doesn't disappoint. The train chase is easily among the decade's most underrated. Come for Billy's abs, stay for a foundational piece of Chicago cinema.

The Last Dragon

"The Last Dragon" makes time for multiple minutes of Debarge's "Rhythm of the Night" music video, and that ranks relatively low on the lunacy scale in "The Last Dragon."

"Bruce Leroy" (Taimak) reaches the end of his martial arts training. All that's left is mastery of a mysterious power called "The Glow." Unfortunately for him, the Shogun of Harlem (Julius Carry) is trying to harness this force for himself, even if it means killing all challengers. To make matters worse, the Man is muscling in on the hottest video dance club in town and forcing Leroy's beloved Laura (Vanity) to play sub-Lauper pop. Where Brucesploitation meets Blaxploitation, there glows "The Last Dragon."

Louis Venosta wrote it like a comic book. Michael Schultz directed it like a cartoon. Motown founder Berry Gordy produced it like a musical. The result is a Rosetta Stone for decades of hip-hop and a roundabout love letter to the 42nd Street grindhouses that inspired it in the first place. The soundtrack is a miracle in its own right, with not one, but two songs that explain the plot of the movie. That's to say nothing of the mutant fish. There's a lot of magic in "Last Dragon" and not just the kind rotoscoped over flying kicks.

The Stunt Man

20th Century Fox didn't know how to sell "The Stunt Man." It was a comedy, drama, romance, thriller, and satire, all successfully, rarely at the same time. As a result, the studio smothered it, along with any chance of another Richard Rush action picture in the foreseeable future. That's what he gets for being the canary in the coal mine.

A buzzard mistakes a tired dog for dead. From his personal helicopter, mad director Peter O'Toole sees an opportunity in desperate fugitive Steve Railsback. Subtle? Heavens no. Thoughtful? "The Stunt Man" is never less. Like any deal with the devil, O'Toole's is all catch — Railsback can hide amongst the production but only if he assumes the identity of the stunt man he unwittingly killed and subjects himself to any danger his director desires.

Call it a game of cat and trapped mouse. O'Toole, content to let underlings mistake his evil for Britishness, pushes Railsback toward ever-more-certain death, presaging a decade obsessed with ever-more-massive explosions. Ego is the thing, ticket sales second. The craft? Somewhere between psychosis and afterthought. If the popcorn munchers are satisfied, the criminal investigations will sort themselves out. It's only gotten more acidic with age.

Police Story 2

The first Police Story was made of righteous anger, after Jackie Chan blew another shot at American audiences on a director who didn't know how to showcase his abilities. If Chan wanted to break out, he'd need to do it himself. So he did, along with approximately 700 pounds of fake glass.

"Police Story 2," released three years and four Chan films later, can't compare to the rattlesnake pitch of its predecessor or the globetrotting scope of its eventual sequel. In all the ways that the rest of the "Police" stories were packaged and presented as Jackie Chan showcases, this one is content to be a bifurcated crime drama starring Jackie Chan.

There's plenty of action — a highlight reel of the last movie reminds viewers who they're messing with — but spread across an often-felt two hours. The first half is a "this-time-it's-personal" revenge thriller. The second half is a mad dash against mad bombers. Either would've made a worthwhile "Police Story" sequel. This film's cardinal sin is choosing both, though the combination does run Jackie satisfyingly ragged. Any complaints about pacing or plot will be gleefully forgotten by the Donkey Kong finale. There may be no standout stunt, but a million bruises are a fair enough trade.

Southern Comfort

Besides Edgar Wright's feature-length recommendation of "The Driver" and the slow-and-steady reappraisal of "Streets of Fire," Walter Hill still evades resurrection. In 1982, he bottled the buddy cop formula with "48 Hrs.," yet "Lethal Weapon" gets most of the credit. His greatest action movie of the decade came out a year prior and hasn't been heard from since.

There's only one color in "Southern Comfort" — olive drab. The bayou bleeds it. The nine Louisiana Army National Guardsmen wear it. The Cajun trappers understand it. Nothing about the film is easy, including its palette. Everything falls apart over a city-slick joke at the locals' expense. One of the weekend warriors opens fire on some hunters with an M60 machine gun. He laughs when they dive for cover, unaware it's just a National Guard exercise and the bullets are blanks. When the hunters strike back with very real weapons, it's only self-defense.

The Guardsmen range from intelligent to ignorant, calm to panicked, cowardly to cruel, but never in the expected combinations and not for long. The threat of dying in a dumb war none of them wanted erodes the entire company. All violent recourse is impotent, a feature-length dry run of the scene in "Predator" where the supermen blow ammo on an empty jungle. Cinematographer Andrew Lazlo, veteran of Hill's "The Warriors," shoots it like waterlogged hell and composer Ry Cooder, vet of just about everything Hill made after, plucks it as love lost. The atmosphere is thick as mud in "Southern Comfort." It sticks just as long.

To Live and Die in L.A.

"To Live and Die in L.A." is a buddy cop story. The title song is performed by Wang Chung. The marquee car chase rivals all vehicular ballet before or since. On paper, it checks every possible box for '80s action movies. What makes it the ultimate '80s action movie, though, is how little it cares.

Secret Service agent Richard Chance doesn't believe in his own last name. He spends his shifts playing cowboy and his downtime jumping off bridges. Some of it's the job — on a good day, cops and robbers through the looking glass — but most of it's the man. Chance doesn't want counterfeiter Rick Masters because he killed his partner — he wants the scumbag because he killed his partner.

William Petersen, worlds away from his equally impressive disappearing act in "Manhunter," struts through the tangerine-tinted scenery like he shaped it with his own hands and scribbled divine law on his lunchbreak. Willem Dafoe's counterfeiter is humane by contrast, at least terrestrial. He takes pride in his art, bills or otherwise. Somewhere in the middle is fluffy-tailed agent Bill Pankow, naively believing it's anything but a cosmic measuring contest and bleeding humanity by the shift for his conviction.

This is a eulogy for the loose cannon. Director William Friedkin buries him better than he was ever celebrated.