'Interstellar' Ending Explained: Join Us In The Space Library As We Ask "Does It Hold Up?"

The very first image we see in Christopher Nolan's Interstellar is a bookshelf with a toy space shuttle on it. There are dust motes in the air, like you might see in the light of an old movie projector, only these aren't from simple house dust. They're from a dust storm.

Interstellar made its original theatrical run back in late 2014 when lead actor Matthew McConaughey was enjoying a career resurgence, colloquially known as the "McConaissance." By now, it's one of those movie titles that could be gathering dust on the shelves of some people's interdimensional Blu-ray libraries. If you're a Nolanite, however, you've likely revisited this film more than once, and if you're streaming it for the first time, the ending may have left you scratching your head. And it's been long enough for us to really dig into it.

Follow us through the movie wormhole as we take a trip back into Nolan's science-fiction epic and explore its ending. Naturally, full spoilers for Interstellar follow.

Simply put, Christopher Nolan owned the movie landscape of the 2000s. He has an impressive filmography overall, but going by the Rotten Tomatoes metric, Interstellar was his worst-reviewed film until Tenet came along with its wacky time inversion. The movie has its defenders, and we ourselves expressed the unpopular opinion that this is Nolan's best, or at least among his best. It's no secret that, as a filmmaker, he's rather preoccupied with time. The question here is, has time been kind to Interstellar?

Mann's Planet is Full of Revelations

Nolan takes a cue from Commissioner Gordon in The Dark Knight in that he likes to "play things pretty close to the chest." You won't see Matt Damon's name advertised in any of the old posters or trailers for Interstellar; and to this day, some people going into the movie for the first time might not be aware that Damon is in it. He's a big-name star, yet Nolan is coy about showing his face.

Early in the movie, he does show us the framed photos of some of the other astronauts who went out seeking inhabitable worlds along with Damon's character, the rather bluntly named Mann. However, the camera jumps back to a full shot of the NASA conference room, cutting away from the close-ups of pictures on the wall — before we can see Mann's face.

Nolan withholds the Damon reveal until McConaughey's character, Coop, gets to Mann's planet, with its frozen clouds and icy secrets. Then, we see Matt and Matthew embrace in a sloppy man-hug as if they're reconciling after all those times that Damon impersonated McConaughey on late-night talk shows, publicly mocking his tendency to appear shirtless in romcoms and other pre-McConaissance flicks.

Next thing you know, Damon/Mann himself is shirtless under a tinfoil tarp, which only deepens the layer of metatextual humor.

Brand (Anne Hathaway) gets an interstellar video message from Murph (Jessica Chastain), and this bursts everyone's bubble because it turns out saving the world was never an option. Plan A was a sham. Mann, Brand, and the doomed Romilly (David Gyasi) realize they were never meant to make it back to Earth. NASA just wanted them to enact Plan B and colonize the stars. The reason that Professor Brand — played by Nolan's good luck charm, Michael Caine — misled them with hopes of Earth's salvation was that he needed them to show God-level empathy and "work together to save the species instead of themselves" and their loved ones.

Romilly already aged 23 years while Mann and Brand were down on that other watery planet, with its ticking time bomb score by Hans Zimmer and its ginormous waves: the size of mountains, you understand, not plot holes. Brand starts weeping about, "The lie. That monstrous lie," and this is one example of how the dialogue does occasionally creak in Nolan's screenplay, which he co-wrote with his brother, Jonathan Nolan.

The other big revelation down on Mann's planet comes when Mann decides to go all Cain and Abel on Coop and kill him. It turns out he faked all the data he was transmitting so NASA would think his planet was habitable and come and rescue him. Otherwise, he'd be left to die alone in space. He says, "The truth is, I never really considered the possibility that my planet wasn't the one."

Less than a year after Interstellar, we'd meet another Space Damon who would "have to science the s**t" out of a similar lonesome scenario in The Martian. This time, though, his character would be a little more well-adjusted to solitude than Mann. As it is, Mann leaves Coop to perish while talking him through his impending demise, the same way that TARS will talk us all through the plot in Interstellar's zany third act.

Ground Control to Major Nolan

Let's back up a second. While Coop and Mann are wrasslin' in space, something else is happening far across the universe.

Casey Affleck punches Topher Grace, mostly because Nolan likes cross-cutting. Jeeps now make dramatic U-turns, cutting through cornfields. To paraphrase Batman's butler, "Some [women] just want to watch the [crops] burn."

Putting some distance between himself and Coop (alas, no funeral homily for Romilly), Mann, whose name flags him as a symbol for "all mankind," attempts docking his stolen lander on the Endurance spacecraft above his frozen tundra planet. Yet sneaky, distrustful TARS, the sarcastic robot with adjustable humor and honesty settings, has disabled the autopilot.

Brand keeps calling for Damon's doctor-man fella over the intercom. "Dr. Mann, please respond." But it's to no avail. Nolan uses sound — quiet, then loud! — to give us a jump scare as the airlock depressurizes and blows, abruptly killing Mann and causing the Endurance to spin wildly out of control (like the movie soon will, you might be thinking).

Coop and Brand, hot on the dead Mann's tail in another lander, try to match the Endurance's fearsome spin. TARS or someone says, "It's not possible." No, sir, it's "necessary," because the script ordains it so.

With a little help from his robot friends, Coop thereby achieves a nigh-impossible docking procedure. Before long, he says sayonara to Brand and flies his own separate shuttle away from her, into a black hole named Gargantua. Now comes the moment where the movie ejects itself pell-mell, through the person of Coop, into a literal black hole of its own device.

For some viewers, Interstellar might never recover after Coop's trip to the space library. This is where we learn that Coop is Murph's mysterious ghost, and has been all along because, you know, gravity, and because, well, love.

The plot takes a big overall turn into take-it-or-leave-it territory. Either you roll with it, or this is where the movie might nuke the fridge and become an epic fail for you.

One thing that needs to be said about Interstellar's climactic Ghost Dad reveal, regardless of whether it works for the viewer on an emotional or intellectual level (we know it appeals to the former at the expense of the latter), is that Nolan telegraphs it from the very beginning. He lays the pipeline for the film's whole ending in its opening minutes. Structurally, you can't fault him for that as a storyteller.

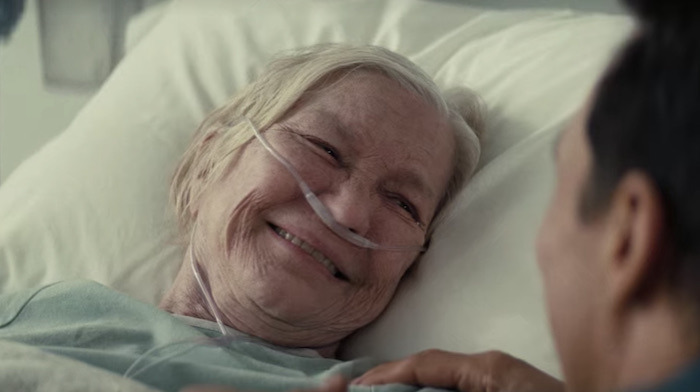

Quick trip back to the beginning. Ellen Burstyn, who embodies the oldest version of Coop's daughter, Murph, is the first talking head we see onscreen in Interstellar. The movie rapidly abandons its faux-documentary conceit, but it's even speedier about introducing the mystery of Murph's ghost, which seems to communicate in Morse, nay, binary code.

Naturally, it's a gravitational anomaly that wants to relay the coordinates of a secret space-faring facility, where her dad will be interrogated by a walking computer cabinet. But the young Murph (Mackenzie Foy) doesn't know this yet. Sitting across from an equally young Timothée Chalamet at the breakfast table, she imparts the knowledge that the ghost has broken her space lander and it keeps knocking books off her shelf. She even guesses the ghost's identity — quite correctly — at one point when she says, "Dad? I thought you were the ghost."

He was. It's true. Which of you smart cookies figured it out beforehand?

All along the way, Nolan sprinkles in these little bread crumbs about who the ghost is, who sent Coop to that facility, who chose him for this world-saving mission, who put that space-time disturbance out near Saturn. It always leaves that question of, "Who are they?" dangling.

Behold, the Movie Gods! Wait, Where Are They?

"A wormhole's not a naturally occurring phenomenon. Someone placed it there."

"Whoever they are, they appear to be looking out for us"

"It came along right as we needed it."

"They've put potentially habitable worlds right within our reach."

Lines like these have a certain self-aware ring to them, almost as if we, the audience, have caught Interstellar red-handed in rationalizing its own convenient plot maneuvers. Someone did this, you see. Someone, the movie gods, put that wormhole there and built that library.

"Somewhere in their fifth dimension, they saved us."

"Who the hell are they? And just why would they want to help us?"

"They constructed this three-dimensional space inside their five-dimensional reality to allow you to understand it."

Again, someone, the movie gods, did these things, the dialogue tells us. They're playing five-dimensional chess with you and they want you to understand them. The problem is, we never meet the movie gods, not like Jodie Foster does with David Morse on the space beach in Contact (a clear influence on Interstellar; two others would be 2001: A Space Odyssey and Steven Soderbergh's Solaris remake, the latter of which had the alacrity to quote Dylan Thomas in space first).

Contrary to what Interstellar itself says, the movie gods in it are not future humans, some unseen "civilization that's evolved past the four dimensions we know." No, the movie gods here are the screenwriters. They're not exactly all-powerful, not in most cases in Hollywood ... unless of course, one or more of them happen to be directing the movie as well.

Checks notes. Interstellar: directed by Christopher Nolan. Confirmed.

Murph says her ghost felt like a person who was trying to tell her something. "Tell" is the operative word. Interstellar shows so much, but it also tells too much. It suckers you into believing it's going to be a show-me movie yet ends as more of a typical tell-me movie.

Blame the time slippage. In Interstellar's third act, the Nolan brothers' script bends over backward to explain itself. Back in the library with Coop (it's out of this world and will bend your mind like that folding cityscape in Inception), TARS radios in out of nowhere just to be helpful and explain what's happening to Coop and us. Together, Coop and TARS litigate and re-litigate the plot the way the at-home audience might still want to do after watching Interstellar.

Coops argues: "That ain't working." The disembodied voice of TARS, on behalf of the Nolans, bites back defiantly: "Yes, it is."

Love, TARS, Love

You know the words to this stretch of dialogue. Sing it:

"I'm going to find a way."

"How, Cooper?"

"Love, TARS. Love."

Lines like that are surreal and obviously meme-worthy. Coop works out that gravity can cross dimensions, including time, and TARS contributes, "Apparently," as if to throw up his non-existent hands and say, "Whelp!"

"Do you have the quantum data?"

"Roger, I have it."

"I am transmitting it on all wavelengths but nothing is getting out, Cooper."

"I can do this. I can do this."

"But such complicated data to a child?"

"Not just any child."

The audience is the child, you understand. Not young Murph. The audience. We are children, we are putty, in the hands of these fifth-dimensional movie gods.

"They have access to infinite time and space, but they're not bound by anything."

Including our feeble logic as audience members, whose disbelief has — at this point in Interstellar — unsuspended itself and gone floating over to the skeptic's corner like an astronaut in zero-G.

To be fair, that's not Murph's experience at all. She turns giddy as Coop communicates with her from the great beyond, courtesy of the force of gravity. Back on Earth, she writes out the secrets of the universe on a notepad and on a chalkboard. Then, she shouts, "Eureka," and tosses her papers. Then, she shrugs, says, "It's traditional," and kisses Topher Grace, smack dab on the lips. Because, yes, that is the traditional thing to do in a Hollywood movie at a moment of supremely satisfying narrative climax like this.

Read back over it yourself — speak it aloud, if you must — and you may soon find that the dialogue in Interstellar plays like the Nolans in conversation with themselves as self-styled movie magicians and with you as a paying customer of theirs.

TARS tells us, "The bulk beings are closing the tesseract," which somehow leaves Coop sling-shotting back to Saturn. Coop then wakes aboard a space station and, sure enough, the doctor informs him that he's on Cooper Station, currently orbiting Saturn. The station is named after his daughter, not him, you big silly.

It sports his original Earth house or a recreation of it. The house has become a museum with velvet ropes. Coop has a brief reunion with his elderly daughter, who is now on her deathbed, surrounded by the rest of his family tree, all strangers to him. Murph tells him, "No parent should have to watch their own child die." Especially not when the child is now older than the parent.

This sends Coop out, looking for something to do, so he steals a shuttle and heads off into the sequel. Of course, there's not really a sequel. That's not Nolan's thing outside Batman movies, but we can imagine one. And that's how Nolan wants to leave the wowed audience for this Prestige-like magic show in space. Imagining.

"Did it work?"

"I think it might have."

Verdict: A Ghost of Greatness Unachieved Haunts Interstellar

In its best moments, Interstellar has a majesty to it that dwarfs the peanut gallery and drowns out the dings of the Movie Sin Counter. The movie is undeniably a technical marvel, filled with beautiful images from the earthbound and space-roving lens of cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema.

Sure, even before we get to that third act with the space library, the script has a few hiccups along the way. Where it mostly falters is in the aforementioned dialogue department. The Nolan brothers write their women emotional. When Chastain first shows up as a middle-aged Murph, she acts irrationally resentful and it feels like forced conflict, more dunderheaded than Dunkirk-tight in terms of screenwriting.

Shouldn't Murph be just a teensy bit more understanding of why her dad left, given that the fate of the whole human race is on the line? That's just one example, mind you. Another is when Brand, the seemingly level-headed scientist, suddenly starts talking about following her heart because love is "observable, powerful," not just something we invented.

Whatever you say, lady. We know it's not really you talking. It's two brothers named Nolan, using you as a mouthpiece for men's dorm-room philosophizing.

These speed bumps aside, Interstellar offers smooth solar-sailing for at least the first half, maybe the first three-quarters, of its running time. Then, it hits a patch of rough space turbulence and gets swallowed up by that black hole, Gargantua.

What we're dealing with here is a classic case of third-act problems. This is 75% of a good movie, which puts it right in the neighborhood of that 72% Tomatometer score, a muted career-low for Nolan (again, until Tenet in 2020).

By touting such a score — for lack of any better shorthand or consensus gathering — we're definitely not trying to "rate a picture the way you'd rate a horse at the racetrack." Martin Scorsese warned against that once, and here in this neck of outer space, we're inclined to respect our elder statesman of moviemaking. That includes Nolan, whose exemplary film career has been going for over two decades.

Ultimately, Interstellar tugs at the heartstrings and flirts with greatness without necessarily achieving full liftoff. One earthbound scene in the movie has Coop's father-in-law and Murph's grandpa, Donald (John Lithgow), remarking on the deficiencies of the "World Famous New York Yankees." It seems the ol' ball team ain't what it used to be on this future Earth, where all that's left on the menu is fritters and corn souffle.

"In my day, we had real ballplayers," Donald bemoans. "Who are these bums?"

Here's a parting image for you. When you think of Interstellar, maybe it's best to forget the unseen interdimensional movie gods and just see this one great movie moment: not the ending of Coop's space adventure, but the ending of his Earth adventure.

When he leaves our planet and his family with it, Coop does so in a memorable, heartbreaking fashion. As he drives away from his farm, McConaughey sells the emotion of it like no one's business. We really believe we're witnessing a man tear himself away from his daughter, ignoring that one-word message: "Stay."

The music swells to a deafening volume and we skip straight to Coop rocketing up from Earth into the silence of space.

"Once you're a parent, you're the ghost of your children's future" And time is a precious resource: Interstellar teaches us that. It slips forever away and can't run backward. Time, as conceptualized visually for the moviegoer, is an onscreen Hamilton wristwatch. Time is a flat circle. It's the son who's left you years of messages, "drifting out there in the darkness" like unanswered prayers. Can you hear this prayer?

As the years go on, maybe we'll all be inclined to look back on Interstellar more kindly, forgiving its shortcomings, waxing nostalgic about Nolan as one of the "real" filmmakers we had in our day. Until then, space cadets, meet you in the movie library, where we'll be browsing for other old titles to revisit ... and in them, perhaps peeking at past versions of ourselves.