25 Years Ago, Pixar's 'Toy Story' Changed Animation Forever

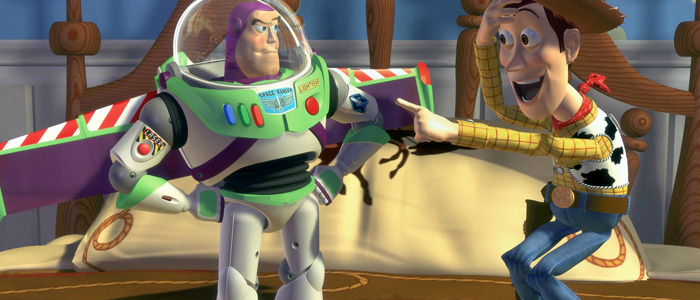

(Infinity and Beyond is a bi-weekly series in which Josh Spiegel looks back at the history and making of every feature film in Pixar's filmography. In today's inaugural edition, he kicks off the column with the movie that started it all: 1995's Toy Story.)There are only a handful of films released in the first century of cinema that can be categorized as truly influential to more than just a few young would-be filmmakers and/or critics. Films such as Birth of a Nation, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Citizen Kane are valuable cinematic items not because of their quality (though the latter two are quite incredible), but because they paved a path for the future of their respective mediums. The films we love now literally could not exist without these titles paving the path for the future.One film that can be safely deemed influential for representing a sea change in the art of animation and the craft of cinema is the 1995 adventure comedy Toy Story. And Pixar Animation Studios, the group that produced and animated the film in the San Francisco area, is now one of the most powerful and dominant forces in all of Hollywood. For a lengthy time, its creative leader wasn't just overseeing Pixar, but also Walt Disney Animation Studios and Walt Disney Imagineering. Though John Lasseter departed the company in acrimony in 2018, Pixar's overall legacy is unblemished. 2020 marks the 25th anniversary of Toy Story, and thus the quarter-century anniversary of computer animation being seen as a viable, and now essentially required, way to make animated features for the whole family. Just as I explored the films of the Disney Renaissance at /Film in 2019, I'm fortunate enough to be doing the same for the entire filmography of Pixar Animation Studios this year with Infinity and Beyond, culminating with discussions of the company's one-two punch in 2020 of Onward and Soul. For now, though, let's start with the humble beginnings of a studio that fought to prove the value of computer animation before becoming its standard bearer.

That’s Not Flying

When people outside of Hollywood hear about reshoots on a given live-action project, they may presume the worst. If a live-action film has to go through millions of dollars' worth of rewrites and reshoots, it's often a sign that the story is not in a good place. Of course, reshoots don't guarantee a film's success or failure with critics or audiences. Look at the two Star Wars Story titles of recent years, Rogue One and Solo. Both went through extensive reshoots, the latter even replacing its directors mid-production. One of them made a billion dollars worldwide. The other one is Solo. Though the whiff of trouble can be true in live-action, and can turn off audiences, it's not quite as simple in the world of animation. Rewriting storylines, dialogue, and character details are the name of the game, and the existence of such revisions rarely implies a film's eventual success or failure.Yet the specter of failure because of studio demands couldn't be far removed from the minds of the Pixar staff who were sitting in a conference room with Disney executives in the fall of 1993. Pixar, led by co-writer and director John Lasseter, had just presented story reels for what would become the first fully-computer-animated feature film. To say that the presentation went poorly is an understatement. In Pixar lore, as discussed in David Price's invaluable studio biography The Pixar Touch, the meeting, taking place on November 19, 1993, was known as the "Black Friday Incident." The film everyone knows and loves wasn't present on that day, even though the story reels featured dialogue performed by Tom Hanks and Tim Allen. Their characters, the neurotic Sheriff Woody and the arrogantly heroic space ranger Buzz Lightyear, had an unpleasant chemistry at the time. What should have been jocular sounded mean-spirited. For a comedy, it didn't seem to be that funny. Instead of wit, there was noxious sarcasm.Lasseter and the team were given three months by the Disney leadership to fix what seemed like an unfixable problem. Whatever else was true, Pixar could only shoulder some of the blame for the largely unfunny story reels they'd presented to Disney. According to Walter Isaacson's biography of the late technological pioneer and Pixar chairman Steve Jobs, Jeffrey Katzenberg asked Disney executive Thomas Schumacher why the reels were so bad. Schumacher's answer was simple: "Because it's not their movie anymore. It's completely not the movie John set out to make."

T-O-Y, Toy

John Lasseter had envisioned a computer-animated feature well over a decade before the Black Friday Incident. In the early 1980s, Lasseter was working at Walt Disney Feature Animation, during a period of time not well-known now for its strong feature output. (One of the projects on which Lasseter is credited is the holiday short film Mickey's Christmas Carol from 1983.) But one of the major technological breakthroughs of the era is a film Disney released in its attempts to capitalize on the widespread success of Star Wars. For years, the 1982 film Tron was well-known as an expensive sci-fi adventure that failed to capture as many hearts and minds at the box office. (And for fans of The Simpsons, it might have been best known as the subject of a joke in a mid-1990s "Treehouse of Horror" episode.) Tron, though, was proof of the viability of computer animation and computer-generated imagery in a major mainstream film. Lasseter didn't work on the project, but when he saw footage of the light-cycle scene from the film, he instantly understood the possibilities that opened up from its very existence. He wasn't content to wait around, either — he pitched Disney's executives at the time on a computer-animated film based on The Brave Little Toaster, in which inanimate objects with human personalities go on an adventure in the hopes of returning to their friendly owner, a loving little boy.The pitch went about as badly as could be expected: Disney rejected it, and soon Lasseter himself, firing him. (The Brave Little Toaster was eventually made as a largely hand-drawn animated film, released in 1987 to a few theaters and eventually gaining a cult fanbase.) Lasseter became a part of Lucasfilm in its post-Return of the Jedi era, specifically working on a subsection of George Lucas's company, the Pixar Image Computer. In the earliest days of Pixar, what Lasseter was doing was less its leading principle and more a way to demonstrate the power of the computer technology Lucasfilm owned. Making computer-animated short films was, in the mid-1980s, just a nice way to convince larger companies that the technology had legs. (Then, as now, there wasn't a lot of money to profit from in making short animated projects.) But once Steve Jobs bought Pixar, Lasseter's work kept coming and gradually gained Pixar a good reputation, with the 1988 short Tin Toy winning the Oscar.

You’ve Got a Friend in Me

Pixar's reputation in the late 1980s was exactly what sparked the interest and attention of Disney's CEO Michael Eisner and his fellow executive Jeffrey Katzenberg. (For anyone who read the Revisiting the Renaissance series, just as Katzenberg had his fingerprints all over a lot of that era of Disney Animation, he's a key figure of the early days of the Pixar/Disney partnership. We'll get to Michael Eisner soon enough.) Disney tried and failed to lure Lasseter back to their animation studio — as Lasseter put it to fellow Pixar honcho Ed Catmull, "I can go to Disney and be a director, or I can stay here and make history."Whatever else is true about John Lasseter now (and this series will grapple with that, don't worry), his vision was dead-on in this situation. Katzenberg and Eisner realized they couldn't get just Lasseter — if they wanted to work with him in any capacity, they'd have to work with the whole of Pixar. By the summer of 1991, after Katzenberg had convinced Pixar that in spite of his tyrannical nature, working with Disney was the right move ("I am a tyrant," he admitted, as captured in Price's book), a deal was announced for the film that would become Toy Story.The lead character from Tin Toy, nicknamed Tinny, was envisioned as the protagonist of Toy Story, though that notion would shift over time. The original treatment by Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, and Pete Docter had Tinny paired with a ventriloquist's dummy on a lengthy journey, in which their antagonist was...Sheriff Woody, terrorizing the other toys in the bedroom of a little boy. But the story changed, as Katzenberg recommended Pixar turn the film into something in the vein of odd-couple buddy films like 48 Hrs. and Midnight Run. Though Katzenberg's recommendations weren't always in the film's best interest — Thomas Schumacher's comment is an indirect critique on Katzenberg's request for the film's humor to be nastier — his buddy-comedy recommendation is one of the most important suggestions in the studio's history.

Strange Things Are Happening

Still, there were character and storytelling shifts to make. Tinny morphed over time from the little tin toy of the 1988 short into Buzz Lightyear (a name inspired by astronaut Buzz Aldrin, and only arrived at after the character's name shifted from, among other options, Lunar Larry). The ventriloquist's dummy was turned into who we know now as Sheriff Woody after the late character designer Bud Luckey recommended changing the character to a cowboy dummy, morphing the battle for dominance between Woody and Buzz into a 50s-era fight between the Western and science-fiction genres. (Since the Toy Story films ostensibly take place in the present day, it's always been odd to imagine a '90s-era kid going nuts over an old-school cowboy doll.)The script that was greenlit by Jeffrey Katzenberg in January 1993 — months before the aforementioned Black Friday Incident — was also heavily influenced by the famed screenwriting teacher Robert McKee. You might know McKee as a forceful figure played by Brian Cox in the brilliant deconstructionist comedy Adaptation., in which the script guru is presented as knowing how to filter all stories down to the same basic struggle, thus creating a dull dramatic result depicted in a bonkers finale. For the Pixar faithful who attended his three-day seminar in the early 1990s, McKee's guidance was invaluable for restructuring the story, centering the conflict and identifying character arcs and motivations that hadn't been previously present.The teachings Pixar took from McKee are likely what saved Toy Story from being gutted entirely. After the Black Friday Incident, Pixar went back to the drawing board as literally as possible. Andrew Stanton holed himself up for weeks to crack the story, while other credited screenwriters like Joss Whedon added color and personality through the dialogue. (Whedon, it should be noted, was still a couple years away from creating his genre-bending cult TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer. His '90s-era feminism was on full display in the making of Toy Story, as he fiercely advocated that Barbie be a butt-kicking part of the new film, a premise that was shot down when the Mattel company declined.)

Falling With Style

Mercifully, the new script passed muster with Disney executives. In February of 1994, Pixar was given the go-ahead to move forward, with actors recording the new dialogue. Tom Hanks, as Sheriff Woody, was always the first choice for John Lasseter and Pixar. Though now we perceive Hanks as the elder statesmen of modern American actors, a Jimmy Stewart type to end all Jimmy Stewart types, in the early 1990s, he had only just begun to make the transition from comic to dramatic acting. As the story goes in The Pixar Touch, when Hanks first arrived for a preliminary meeting with Pixar, the animators didn't recognize him. He was extremely gaunt and had a shaved head, as he was in the middle of filming Jonathan Demme's Philadelphia, which would be his first major shift into serious performances.As was the case with some other Disney animated fare, the animators convinced the actor to join the project by showcasing how his voice could work in animation — they took audio from his role in Turner and Hooch and paired it with Woody, selling the actor on joining the project. This came before the Black Friday Incident, though Hanks was likely on board with the script changes, having frustratedly pointed out during one early recording session that Woody sounded like a jerk. Casting Buzz Lightyear was always a bit more challenging for Pixar. Thanks to the behind-the-scenes details of Monsters, Inc., it's now well-known that comedian Billy Crystal was offered the role of Buzz, but turned it down. (The fact that Toy Story became such a monstrous hit is largely why Crystal signed on instantly to play Mike Wazowski in that 2001 comedy.) Eventually, after striking out with comic giants like Bill Murray and Jim Carrey, John Lasseter alighted upon the comedian and actor who played a faux-gruff handyman on a show-within-a-show in Home Improvement. Tim Allen, still in the days before he would star in The Santa Clause, signed on instantly.

I Will Go Sailing

For Disney, it was encouraging to see that the gamble of Toy Story was finally coming together. There was, however, one very large aspect of the story that remained unresolved and concerning for the House of Mouse. Toy Story was, yes, an animated film with characters who had hopes and dreams. It would have an ensemble cast with some recognizable names, even outside Hanks and Allen. But John Lasseter very stridently wanted to buck a specific trend that had helped ensure the success of Disney Animation in the 1990s. There would be, to paraphrase a Monty Python bit, no singing. Whedon, in an Entertainment Weekly article in 1995, agreed with the decision, noting, "It would have been a really bad musical." Disney wasn't thrilled, but they let Pixar have that victory, somewhat. The compromise that Disney imposed was that there would be songs, just none performed by the characters. (That, by the way, is a compromise first broken in the first Toy Story sequel, but we'll get there eventually.) In the vein of the patron saint of disaffected-protagonist dramas, The Graduate, there are a handful of songs in Toy Story that essentially comment on the proceedings without actually being performed by any characters. Disney and Pixar reached out to the well-liked composer and musician Randy Newman to write the score and songs, the beginning of a partnership that's extended through multiple decades. Newman has composed the score to 11 films from Pixar and Disney Animation, including Toy Story 4.As the film came together, Pixar's animators couldn't quite perceive if it was going to be a hit. Despite receiving a choice release date — the Thanksgiving weekend in 1995 — seeing the disparate pieces of the film on their own couldn't help the animators in terms of grasping the film's overall creative success. As per Price's book, some animators thought the film would be a flop. So too, at one early point, did Steve Jobs, who had reached out to other companies about the prospect of selling Pixar.

The Perfect Time to Panic

In hindsight, of course, it's almost perversely delightful to imagine that people at Pixar were worried about Toy Story. The end result is one of the funniest comedies ever made, and one of the sharpest, most economically written screenplays of the modern era. (The film deservedly was nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the Oscars, losing to the twisty The Usual Suspects.) Hanks and Allen are just two members of a larger ensemble of character actors and performers with such easily identifiable voices that a single line delivery communicates character development in ways that more detailed dialogue couldn't. When you hear Rex or Mr. Potato Head speak for the first time, all you need to know is the tremulous voice of Wallace Shawn or the cutting tones of Don Rickles to understand exactly who these characters are. Adults could understand the double joke of Mr. Potato Head using the phrase, "Ya hockey puck," but they could also instantly understand what that character's attitude would be. Toy Story is, like many early animated films, very short, clocking in at just 81 minutes. But tight and precise writing and casting enable the film to dispense with exposition and heavy-handed characterization, getting right to the action without feeling rushed.Perhaps what's most remarkable about Toy Story in 2020 is that there aren't any strong signs of reshuffling character beats, or heavy rewrites of any kind. The story of how Sheriff Woody has to deal with the fact that he may no longer be the favorite toy of his owner Andy, thanks to the unwelcome arrival of the cool new space toy Buzz Lightyear, is not only taken surprisingly seriously, but it unintentionally reflects one of the major aftereffects of the film. The struggle between a cool new toy and an old-fashioned toy can be mirrored in how hand-drawn animation has been supplanted by computer animation. In 1995, that extratextual struggle didn't exist; Toy Story, like Tron, could have landed with a thud in theaters, leading to further prevalence of hand-drawn animation. Instead, the film was just like Buzz himself, soaring at even the most unexpected moments.Toy Story simply remains extremely well-written, snappy, and with dialogue that still holds up remarkably well. Though the computer technology has unquestionably improved — I adore this film more than any other Pixar title, and I will be the first to tell you it's the weakest-looking of their filmography — the story and characters are practically perfect in every way. Hanks has rarely been funnier in the intervening quarter-century (in part because he's made far fewer comedies), and Allen arguably delivers his best performance of the quadrilogy in full-on arrogant mode. His bluffed-up braggadocio is a perfect fit for Buzz before he realizes that what Woody's been saying all along — "YOU. ARE. A. TOY!!!" — is true. Toy Story, unlike its follow-ups, doesn't lean quite so heavily on tear-jerking emotion, but is still surprisingly poignant during Buzz's existential crisis.

A Sad, Strange Little Man

It's safe to say that few people were prepared for Toy Story to not just work, but to be a massive success. The debut computer-animated film from the upstart Emeryville, California-based studio was not expected to become the highest-grossing film of 1995. And yet, Toy Story was an out-of-the-box hit. Among the many unprepared parties were those who you might have thought were the most obvious champions of a film about toys: toy companies. Both because of skepticism surrounding the viability of a fully computer-animated film, and because of not having enough lead time, when Disney brought the film to an industry trade show in early 1995, a small company called Thinkway Toys snatched up the rights.And lo and behold, Thinkway ended up with a golden goose. Though some of the toys in the film are actual toys, such as Mr. Potato Head, Woody and Buzz were both entirely new. Even Thinkway wasn't fully prepared — an in-joke in Toy Story 2 where Barbie (who did become a part of the franchise after Mattel realized how big a hit the first film was) gives a tour in a toy store and mentions how "short-sighted" companies didn't expect high demand for Buzz Lightyear toys is a specific reference to real life. It was, of course, a good problem for Disney and Pixar: better to have people all around the country love your movie instead of flat-out ignoring it. People did love Toy Story. Critics gave the film high marks, and it's considered one of the greatest animated films of all time. Audiences around the world went to the film in droves. Aside from that Best Original Screenplay Oscar nomination (to note, Toy Story became the first animated film ever to receive a nomination for writing), Lasseter won a special Oscar for the achievements the film represented.Toy Story was an unqualified success. The darkness of the Black Friday Incident had evaporated, in more ways than one. By the time the film was released, Jeffrey Katzenberg — the man who had been so dogged in bringing Pixar into the Disney fold — was no longer part of the Walt Disney Company. Michael Eisner was thrilled at the film's success, having even suggested a final joke in the story, letting it close on the image of Woody and Buzz realizing that their owner Andy now has a dog. Everything should have been perfect. Lasseter had been proven right. There was an audience for computer-animated films, and it was clamoring for more. Pixar was prepared to tell a new story of its own, and Disney would happily distribute it. It was going to be all about ants. That was the good news.The bad news? Well, Jeffrey Katzenberg had left Disney to create an animation studio of his own, one that would also use computer-animated imagery to tell stories. His studio's first film...well, it was also going to be about ants. And Katzenberg wanted his movie to arrive first. Next Time: A rivalry on a very tiny scale.