"A Bloody Bore And Embarrassment Of The First Magnitude": What Critics Said About 'The Shining' In 1980

(Welcome to The Film Historiography, a series that explores the initial reactions to important, iconic, and memorable films.)

"Writing about Stanley Kubrick's The Shining, which is now playing at the Capitol Theater, is a lot like writing about God or politics. Everybody's doing it." - Vivi Mannuzza, The Berkshire Eagle

In the late 1970s, Stanley Kubrick set out to make the "ultimate horror film." Bringing together his mastery of cinema as an artform – and working from a much-beloved Stephen King novel – Kubrick labored to bring to the screen The Shining, the now-iconic horror film about isolation, domestic violence, and the bad places in the world that call to broken people. Fans flocked to see the film, which diverged early and often from King's novel; disappointed by the Kubrick's creative liberties with the novel, The Shining labored as an arthouse curio for years before finally earning its place atop the modern horror canon.As far as historiographies goes, it's mostly true. Kubrick may indeed have set out to create the "ultimate horror film" – though that phrase seems more directly attributable to a May 1980 Newsweek article hyping the film than any direct quote from Kubrick himself – but he did so at a time when both horror and Stephen King were capturing the imagination of mainstream audiences everywhere. Hollywood was still adjusting to a new wave of horror films like Halloween (1978), The Amityville Horror (1979), and Alien (1979), and Kubrick's meticulous shot construction and melodramatic character work seemed at odds with the naturalistic direction of the genre.These were the threads that regional film critics were running with when The Shining hit theaters in May 1980. While the overarching narrative remains the same – it was underappreciated, it was misunderstood – the reasons for this are rooted in these cultural touchpoints of the era. As we look forward to Mike Flanagan's Doctor Sleep, a sequel to both Kubrick and King's versions of The Shining, it's worth looking back at the critics and the conversations that helped shape the film's legacy for the next 30 years.

Deviations from the Book

For contemporary critics, one of the major sticking points of Kubrick's adaptation was his departures from the source material. King's novel was a bestseller; you only need to read contemporary reviews of Kubrick's film (and note how many critics reference their own experience with the novel) to understand the cultural impact that the novel had. And since Kubrick's production process was anything but quick, even pre-internet audiences had to struggle with the knowledge that Kubrick had tinkered with the novel and created something entirely his own."News of deviations from the novel are reported every so often in Cinemafantastique, the American movie magazine that for the past decade has been patrolling the horror, science-fiction and fantasy genres," William Wilson wrote for the New York Times newswire in May of 1980. "It whispers, for instance, that the roque court may have given way to a computer game room, and the roque mallet that figures so prominently in Jack's pursuit of Danny may now be a baseball bat, that Room 217 may be changed to Room 237 'for legal reasons,' that the corpse in its bathtub may be shot from the waist up only."This knowledge gave writers a jumping-off point in their review of the film. Critics like to think that they evaluate a work of art devoid of context and cultural inference, but that is hardly the case; we need look no further than the number of reviews that opine on the state of 'elevated horror' or the Times Up movement to see the tendrils that connect popular culture and cinema. For those film critics, the tension between the book and the film – and the perceived differences between the two narratives – become a key talking point in how they engaged with their audiences. "Stephen King's novel, The Shining, is a piece of pulp so terrifying that your skin crawls as you turn its pages," wrote Dayton Daily News critic Hal Lipper. "Director Stanley Kubrick's cinematic adaptation of the book, however, rarely raises a goose pimple." "[Kubrick] has taken one of the most widely read blockbuster novels of recent times," wrote The Sun critic John Weeks, "and produced The Shining, which is a stiff and haggard shadow of Stephen King's robustly terrifying novel." The Gazette's Mike Deupree was even more backhanded in his criticism. "The novel was quite clear about the house's personality, the horrible things that had happened there, why Jack was going insane. The movie is, to be kind, open to interpretation on that score." Still, not every critic was turned off by Kubrick's creative liberties. "Kubrick has always used the text as a jumping-off point for his singular vision," wrote then-editor of the Argus Leader, Marshall Fine. "The key to Kubrick, however, is understanding that the text is never sacred and that directorial invention and intervention are the keys to the finished product." Fine was also careful to call out the differences between the two mediums, noting that the "celluloid image" and the "printed word" are "very different media, challenging the imagination in wildly varying manners."There were even those who recognized this debate for what is was – nothing new, and nothing to resolved with Kubrick leading the charge. "Frankly," wrote Fort Lauderdale News editor Jack Zink, "the movie is neither as bad nor as good as either extreme has made it out to be. And as for the film's distortions of the novel, that argument has been with us since the advent of the movie camera itself and is never likely to be resolved."

The Shifting Face of Horror

But King's novel was not the obstacle in Kubrick's way. Once it was declared – rightly or wrongly – that Kubrick was trying to create "the ultimate horror film," The Shining became caught up in the increasingly complex landscape of modern horror movies. It's one thing to compare The Shining to the rest of Kubrick's work, or even to compare The Shining to King's original novel; it's quite another entirely to compare Kubrick to filmmakers like John Carpenter, Ridley Scott, or William Friedkin at the height of their cultural influence.Much of this is timing. When Warner Bros. released its now-iconic first trailer for the film, fans began to anticipate a horror film that would do more than entertain – it would change the very nature of the horror genre itself. They weren't excited because they thought that Kubrick's film would be literary or give the horror genre an important shot the arm with mainstream critics across the country. They were excited because the film was meant to be scary. And even the most ardent Kubrick fans were somewhat disappointed. "As for all the controversy surrounding the movie's rating – just weeks before it was set to open, it had received an X rating which was changed to R with minor editing," wrote Call-Chronicle film critic Dale Schneck, "It's hard to imagine why The Shining ever had anyone concerned over the film's violence. Compared with current fare like Friday the 13th and Cruising, The Shining comes off like a pussycat." While The Shining has plenty of individual moments that jump off the screen, it lacks many of the dark corners and manufactured jump scares that blend so nicely into even the highest-concept horror. This became one of the primary sentiments wove into contemporary reviews – when compared to the progressive (and sometimes exploitative) fare popping up in movie theaters across the country, the violence present in The Shining was more smoke than fire. Joe Baltake, movie critic for the Philadelphia Daily News, devoted an entire paragraph of his review to how differently the Overlook Hotel bleeds versus the house in Stuart Rosenberg's The Amityville Horror. "Unlike the situation in Amityville," Baltake wrote, "there's no point to [the blood] here. It exists only for effect." Even positive reviews found the horror lacking. John Omwake, the Entertainment Editor of the Kingsport Times-News, lavished praise over Kubrick's "technical wizardry" in the film, noting that the filmmaker was the "Rubens or Van Dyke of cinema" and "a true master of the medium." Still, even he felt that the film was nowhere near as scary as it had been billed. "More serious is the strange lack of terror which marks what should have been the ultimate horror movie," Omwake wrote, yet-again making note of Kubrick's contentious ambition. "In straining out the supernatural in favor of mere insanity, Kubrick also removed much of the terror."

All Work and No Mugging Makes Jack Go Crazy

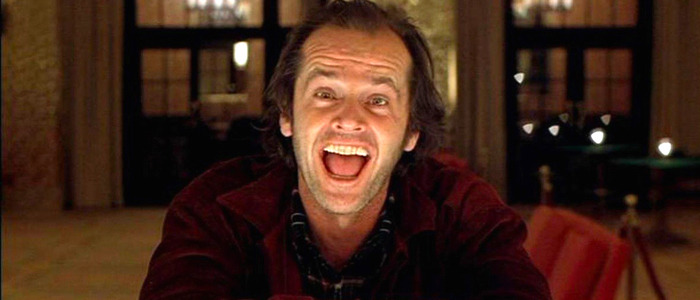

Finally, there's the character of Jack Torrance. Jack Nicholson was a five-time Oscar nominee by the time he signed onto The Shining – having secured his first win as Best Actor in a Leading Role for 1975's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest – and his screen presence had already crystallized as a performer with unmatched intensity onscreen. As part of the publicity for the film, Kubrick even went on record as suggesting that Nicholson was the most obvious selection to play the role of the fractured writer and abusive husband, but the character's quick descent into madness had some critics wondering if Kubrick wasn't just playing into some of Nicholson's worst habits."Nicholson's whole antic, mugging, game-playing performance seems kind of a put-on," wrote Minneapolis Tribune critic Will Jones, "a teacher lapsed into the role of classroom cut-up." Others agreed. "Nicholson, who began his acting career in fright films in the early Sixties, has some thoroughly creepy moments," admitted The Record film critic Jim Wright, "but in the latter stages of the story he becomes such a parody of a lunatic that he actually diminishes the horror." Springfield Leader and Press Jim Larsen passionately defended the film – going so far as to suggest that Kubrick's movie did indeed deserve an X rating – but even he was confused as to the nature of Nicholson's performance. "Nicholson is something of a disappointment," he wrote, "telegraphing his moves early in the picture and mugging it up a bit. But he is suitably demonic when it counts and convincingly crazy." Still, not every critic felt that Nicholson went too far. Evening Journal's Ray Finocchiaro praised the actor's performance at great length in an otherwise-mixed review, describing Nicholson's facial features as instrumental the success of the character. "Nicholson, whose sardonic smile and arched eyebrows convey more pent-up evil than most studio special-effects departments could conjured," he wrote, "make a convincing transition to insanity with a demonic sense of humor that won't quit." Newshouse News Service's Richard Freedman was even more effusive in his praise. "Nicholson has never been more furiously alive on the screen – his maniacal leer is one of the most searing images to appear on this screen this year, and it sticks in your mind long after the movie has ended."

Ahead of the Curve

And yet, for all these contrasting analyses, there were a few critics whose evaluation of The Shining would stand the test of time. Those who appreciated Kubrick for his austerity – not despite it – appreciated the blend of pastoral images and madness that drove Kubrick's adaptation of the film. "Kubrick's Shining may be occasionally illogical or surrealistic, or even muddled," wrote Democrat and Chronicle editor Jack Garner, "but so are your nightmares, and so are the minds of the insane."Perhaps the final word belongs to Ron Cowan, reporter for the Oregon Statesman, who offered a few prescient words on the endless debates we were destined to have about Kubrick's film. "Some day some film pundit may christen Stanley Kubrick's The Shining as a masterwork, or even a 'masterpiece of modern horror' as the ads are prematurely claiming," he wrote. "And it is a richly produced movie of fine detail. However, it is also a bloody bore and embarrassment of the first magnitude for Kubrick and star Jack Nicholson." With Doctor Sleep soon to hit theaters, and people ready to re-litigate their feelings about The Shining once more, let us once again argue Kubrick's "ultimate" horror film After all, like God or politics, everyone is doing it.