20 Years Later, 'The Limey' Is Steven Soderbergh's Most Underrated And Most Daring Movie

If there is an art to a good director's commentary, then the commentary track for The Limey is the equivalent of Picasso's Guernica. Director Steven Soderbergh and writer Lem Dobbs appear on the track, and it doesn't begin the way a traditional commentary does, with the awkward easing-in to a feature-length discursive exploration of what's playing out on screen. Instead, to start the commentary is to feel like you've skipped to the middle, as it begins with the two men mid-argument. The commentary itself mirrors the jangled, jittery and unexpectedly unstuck-in-time narrative unfolding on screen, as we gradually learn that Dobbs — who respects Soderbergh plenty — is frustrated at how his script became the elliptical crime drama that remains the director's very best film.

Tell Me About Jenny

From the writer's perspective, it's easy to spot the frustration. The Limey, as wonderful as it is, rarely seems like the kind of film whose greatest asset is its script. The premise is straight out of a seedy little paperback you might read on a cross-country flight, hiding it behind the airline magazine so as to not arouse suspicion among your fellow passengers. In the stark opening sequence, set to The Who's "The Seeker", we meet Wilson (Terence Stamp), a raffish British ex-con who's landed in Los Angeles to get to the bottom of the death of his adult daughter, Jenny. Doing so means Wilson will wind up tangling with some Angeleno criminals as well as a shady record producer (Peter Fonda), all in the name of justice over his estranged daughter.Soderbergh has spoken often about his work being influenced by the British director Richard Lester, whose work ranged as far back as directing the Beatles in A Hard Day's Night to helming (at least some of) Superman II. Soderbergh's admiration and appreciation of Lester's work isn't just lip service, either; he and Lester had a long-ranging conversation that comprised the 2000 book Getting Away With It. Soderbergh's stylistic preferences in The Limey are perhaps most directly influenced by Lester's work, with a plethora of unexpected jump cuts, juxtaposing sound from one scene into another scene that might be taking place much earlier (as in, decades earlier) or later in Wilson's saga, and other flourishes. These weird, unorthodox methods are unexpectedly quite successful, because all they do is put us in Wilson's fractured state of mind, as he tries to maintain his cool while grasping the level of seediness and corruption in the L.A. music scene. So much of the film, from Sarah Flack's crisp editing that's designed to keep you off guard to Edward Lachman's handheld cinematography to Cliff Martinez's thrumming, moody, and repetitive score, contributes to the off-kilter, scummy vibe. For Soderbergh, The Limey also represented an important step forward in cementing his comeback as a filmmaker to watch.

Tea Leaves

Soderbergh all but burst onto the independent scene in the late-1980s with sex, lies, and videotape, a piercing character study that not only made his name but helped vault the Sundance Film Festival into the larger cultural consciousness as a recognizable arbiter of good indie taste. Though Soderbergh never stopped making films, his other 1990s-era films, from the fourth-wall-breaking Schizopolis to the period drama King of the Hill, never had quite the same impact.The summer of 1998 provided the filmmaker a chance to both utilize his own distinctive auteurist flourishes with a more commercial story. Out of Sight, the adaptation of Elmore Leonard's novel, was an awakening for audiences not only to Soderbergh's talent but to the talents of its stars, George Clooney, who was still trying to break out of his TV-actor mold at the time, and Jennifer Lopez, who's now receiving critical hosannas for her work in Hustlers, praise she hasn't received at the same level since her role here as U.S. Marshal Karen Sisco. Out of Sight was a modest hit, grossing just $37 million domestically in the summer of 1998 as a counterprogramming option for adults who didn't want to just watch an explosion-heavy blockbuster. But it signaled to Hollywood that Soderbergh's quirkiness could be harnessed for more straightforward stories — there, too, some of the elliptical style of The Limey is present in an intensely erotic sex scene between Sisco and Clooney's criminal Jack Foley, or in its screwed-up timeline.

I’m In Your Manor Now

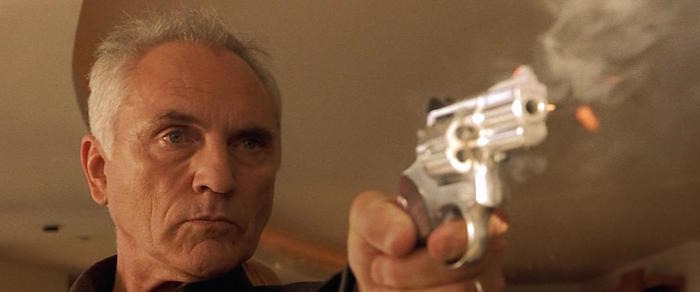

It's easy, deceptively so, to look at The Limey as another aberration on Soderbergh's C.V. It was a low-budget ($10 million) crime drama, with an even lower box-office gross ($3.2 million). The year after The Limey, Soderbergh pulled off an incredible feat, garnering two Academy Award nominations for Best Director, for both Erin Brockovich and Traffic, the latter of which got him the Oscar. The year after that, he helmed the remake of Ocean's Eleven, still one of the biggest hits of his career and one of the most plainly enjoyable films of the last 20 years, featuring an ensemble cast full of stars he's worked with a number of times, from Clooney to Matt Damon and Julia Roberts. The Limey mostly (but not entirely) features actors he either never worked with again or did so only briefly. (Stamp fits the latter camp, making a very brief cameo in the little-seen Full Frontal.) But those actors made an indelible impact in this single film, both thanks to Dobbs' grim, straightforward script (or the terse version of it that we get on camera) and to Soderbergh's unflinching direction. In the intervening 20 years, one of the most memorable moments of the film has become an easy pick for the kind of movie scene that you cannot help but rewatch on YouTube. It's a simple enough setpiece, in which Wilson visits a group of toughs in a nondescript warehouse, knowing that they have some connection to his daughter Jenny; after they initially beat Wilson up, he returns with a small revolver, kills most of the men, only to leave one after whom he shouts (with blood splattered on his face), "You tell them! Tell them I'm coming! Tell them I'm f***ing coming!"Stamp's committed performance — switching within these few minutes from a deliberate stereotype of a loping Englishman with a cartoonishly Cockney accent to a stone-faced killer — makes the scene memorable. But so too do Soderbergh's directorial choices. The decision to feature a couple of jump-cuts as we watch the lead tough go into lurid detail about how he wanted to sexually assault Wilson's dead daughter, as well as the hand-held camera staying pointedly outside the warehouse as Wilson returns to enact murderous justice all contribute to a viscerally entertaining, ruthless sequence in a film full of them.This scene also strikes an important balance that has become something of a hallmark of Soderbergh's career, in which he's often made one for "them" (being the studio system) and one for himself. Movies like Out of Sight and Ocean's Eleven are as close as Soderbergh has gotten on a big-budget level to making something for everyone. They feature A-List celebrities in easily marketable stories with crowd-pleasing moments, but these films are also filtered through a distinct 70s-era vibe that feels stridently outside of the Hollywood system. More often than not, in between his bigger successes, Soderbergh makes a movie like Bubble or The Good German, films that exist as much as experiments as they do features. And that mentality was first truly tested with The Limey.

Standing on Trust

One of the film's charms is its brevity — it's just 89 minutes long, and some part of that running time includes flashbacks to Wilson's life as a younger man. Except those flashbacks are scenes from another film, the 1967 Ken Loach kitchen-sink drama Poor Cow. There's added resonance to these flashbacks, because it's not one of those lazy tricks wherein the audience is shown a photo of a character from a younger time, clearly doctored in some way. When we see the young Wilson, it may not be Terence Stamp as Wilson, but it is Stamp as a much younger, more callow man. Jumping back to the weather-beaten face of the longtime con is almost gasp-inducing. The entire film is infused with this sense of the intensity of the passage of time, the experimental element being a sense of watching old hands at cinema get one more shot in the spotlight.The ruthlessness of time aside — which plays in as much to the slimeball Fonda plays, meant to be a musical icon of the 60s counterculture gone to seed, as if Fonda's Easy Rider-era stardom could be transferred over to rock music instead of movies — The Limey is a darkly funny thriller even as it careens towards a tragic conclusion. Wilson's first encounter with Fonda's character, Terry Valentine, comes at a swanky party at his house in the Hollywood Hills, as we see multiple versions of what could happen upon their first meeting, and then the actual encounter, coupled with a perfectly framed moment in which Wilson takes down a security guard in the background of an inane bit of small talk. There's also a deadpan scene in which Wilson is brought to a DEA investigator (Bill Duke, who recently appeared in Soderbergh's excellent Netflix film High Flying Bird), with the former putting on his best Cockney accent, full of nonsensical slang in a fast-paced monologue, and getting the dry reply, "There's one thing I don't understand. The thing I don't understand is every motherf***ing word you're saying." The scene largely succeeds in spite of many of the film's stylistic and aesthetic choices, one of those moments that reflects the toughness of Dobbs' story.Such is the entirety of The Limey, a film that works because of carefully designed and modulated directorial choices, sometimes (if not often) in defiance of the script being filmed. Lem Dobbs may have been frustrated in some sense by Soderbergh's filtering of his script through a visual sense, but the two men would work again on the pulpy 2011 thriller Haywire, itself a memorably intense B-movie with a great cast. But The Limey remains the peak of its director's career, who has since made many wonderful films, but few that were so able to strip down to the very core the old-school style that has made his name in the last two decades.