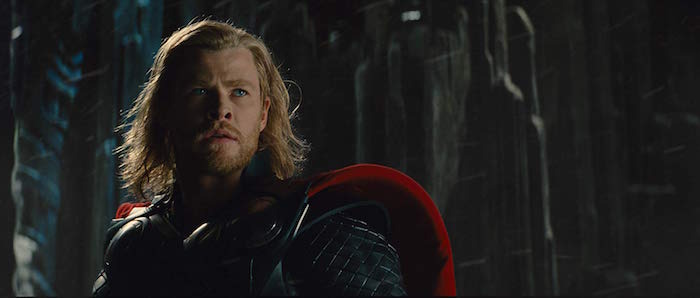

Road To Endgame: 'Thor' Expands The MCU Using Fantasy, Examinations Of Masculinity, And Chris Hemsworth Hotness

(Welcome to Road to Endgame, where we revisit all 22 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask, "How did we get here?" In this edition: Thor sets a new tone for the MCU, but continues its muddled approach to warfare.)After three relatively grounded sci-fi action flicks, the Marvel Cinematic Universe took a leap of faith and ventured into the cosmos. While Iron Man and The Incredible Hulk established the series' shaky politics, Kenneth Branagh's Thor redefines the visual and tonal language of the MCU. However, the film still falls back on the major problems of its predecessors, in the way that it frames its conflict.While messy from a character standpoint, the finished product walks a line that was, at the time, unique in the superhero genre. It straddles two distinct tones that often seem at loggerheads: Earth-bound naturalism, and operatic space-drama. This combination of styles would re-appear in Guardians of the Galaxy, in which they're married far more smoothly, but their wild clash in Branagh's Thor feels textually appropriate. It's what the film is about at its core.

A Bridge Between Worlds

Prior to directing Thor, Kenneth Branagh's filmography included Twelfth Night, Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet, In the Bleak Midwinter (the story of a man fighting depression by putting on a production of Hamlet), Love's Labour's Lost, and As You Like It.If you count his role as Iago in Oliver Parker's Othello, that's as many Shakespeare adaptations as Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa and Vishal Bhardwaj combined, arguably making Branagh the Bard's biggest fanboy. He's exactly who you call to make a grandiose family drama about an aged king, an ambitious prince and the snake in his ear. What makes Thor such an oddity though, is that in addition to being "Shakespeare In Space," it's also a fish-out-of-water alien comedy bordering on slapstick.The majority of the film's runtime takes place on Earth, where Thor (Chris Hemsworth), the banished God of Thunder, smashes a mug of hot cocoa, walks into a pet store demanding a horse, gets tranquilized in the butt, is tasered by Kat Dennings, and gets hit by a car on more than one occasion. Taika Waititi's Thor: Ragnarok may have pushed Marvel to its farcical limit, but the seeds for Thor-centric comedy have been in place for quite some time.A drama about the complications of royal lineage and a comedy about a brutish space oaf in small-town New Mexico ought not to mix. In many ways, they don't; they may as well be two different films. In dramatizing the divide between them, Marvel also set the stage for The Avengers, in which a scorned space-prince leads an alien army into New York City. However, en route to this major crossover, Thor told a character story that brought humour to the fore, but missed the mark where it mattered.

Thor’s Journey

Thor is a warmonger. He comes from a lineage of warmongers, and despite his father's shifting attitude towards violent conflict — mere backdrop here, but it's made to pay off greatly in Thor: Ragnarok — the Asgardian prince seeks out battle against the Frost Giants, for any reason and at any opportunity. During his banishment from the kingdom, he has a change of heart about how best to use his weapons, not unlike Tony Stark in his debut film.Thor's newfound humility however, comes not through seeing the ill effects of war, but through experiencing the kindness of others. He is adrift in this new world, unworthy of his hammer and unable to regain his regal identity. This very regality, and all its implications, are called into question when he arrives on Earth, though they never quite factor into Thor's arc as a character.Thor's ascension to the Asgardian throne depends on two things: being his father's son, and being a fearsome warrior. His conquests involve charging into battle and physically besting his opponents. He even wields a historically phallic symbol — this is how his hammer was depicted in in Norse mythology — without which he's rendered limp and powerless.The first battle we see Thor engaged in, with the Frost Giants of Jotunheim, comes not through necessity, but through his desire to dominate an already vulnerable people after having his fears stoked and manipulated. "It's the only way to ensure the safety of our borders!" he says, of a war his father already fought; a fitting extension of a series already steeped in post-9/11 politics. Though, its resolutions later on leave much to be desired.As Thor is about to come to his senses and retreat from battle, he's provoked when one of the Frost Giants refers to him as "princess." Having his masculinity questioned not only infuriates Thor, but sets the film's events in motion. His stranger-in-a-strange-land story is just as much about experiencing new cultures and technologies as it is about his relationship to Jane Foster (Natalie Portman), a woman whose point of view the film endorses to a significant degree as it attempts to dismantle Thor's perspective.In fact, the first time we ever see Thor on screen, we see him through Jane's eyes.

The Gender Politics of Thor, AKA Thor is Hot

Thor is a rugged, chiseled superhero, and the first Marvel hunk we see from a woman's point of view. Thor began the Marvel trend of finding excuses for its men to be shirtless (turning even Chris Pratt of Parks and Recreation into a "Hollywood Chris"), thus catering to audiences who enjoy the action genre but find it lacking in male eye-candy.Not only does the film put Thor's physicality on display, its lens also caters to women in several ways usually tailored to men. Jane Foster, for instance, is a bumbling, nerdy scientists who gets the supermodel-hot guy in the end, rather than being a trophy for Thor's troubles. And while Jane certainly influences Thor's character arc — she helps him change by showing him kindness — she also benefits professionally from their relationship. Thor's mere existence is a confirmation of her life's work, and he even sits her down to validate her research under the stars.During their interactions, the film begins to feel like a romantic comedy. Where Thor is concerned, a character who starts out so hard-headedly masculine, this is a good thing. Most of the film is about two characters from different worlds — in this case, literally — and with different outlooks, overcoming quirky odds and ending up together (well, nearly). Strip away all the space stuff, and what you're left with is a rich, pig-headed playboy helping a girl get her diary back (and learning to cook eggs for other people, instead of scarfing down Poptarts solo).Thor comes from a place of antiquity, despite its futuristic technology. Asgard is a patriarchal monarchy, wherein women are usually court maidens, like Thor's mother Frigga (Rene Russo), since the kingdom's affairs are handled by the King and his sons. Rare exceptions like Lady Sif (Jamie Alexander), a female warrior, fulfill traditionally masculine roles in the hierarchy. Thor himself may be relatively forward-thinking in this regard — from their brief interactions, he appears to have supported Sif's efforts as a soldier — but it isn't until he arrives on Earth that he meets a woman who's also a leader in her field.More importantly, the woman in question, Jane, has no physical powers. Rather, she studies the physical. Her job is to inspect and investigate advanced astrophysics, the very magic that Thor has, up until this point, taken for granted. Essentially, her job is to learn about Thor himself. Her function in society involves progress through understanding, rather than knocking things down with a hammer. It's this understanding nature that draws Thor to her, as he attempts to introspect, and answer a fundamental question:Who is Thor?

Who is Thor?

The film's Asgard-set drama is expressed with clarity. Thor's violent ambitions, exacerbated by his scheming brother Loki (Tom Hiddleston), lead to his banishment. In Thor's absence, Loki's stellar scenes with Odin (Anthony Hopkins) provide a raw emotional backbone for the film's more melodramatic half.Loki is the son of two warring kings, Odin and Laufey, and he was adopted for the express purpose of forging peace between Asgard and Jotunheim. In most mythological stories, he'd be the hero. But despite Odin's genuine love for him, Loki has neither a throne to sit on, nor a sense of belonging. Not when his older brother Thor was granted both by birthright.Odin seems to regret this discrepancy in how he raised his sons, but he also seems unwilling to step outside his kingdom's traditions in order to challenge them (a dropped thread that's also picked up later in the series). You could use any scene between Hiddleston and/or Hopkins to teach a masterclass in Shakespearean performance, but unfortunately, Thor's Earth-bound story doesn't have quite the same dramatic deftness."Who is Thor?" is the central dramatic premise of the film, and a question that comes up often. Thor is a warmonger, but what else? He is a prince, but what more? Who is he when his powers are stripped away, and he no longer has war and symbols of masculinity to define him? These are questions asked by the character, but ones the film never finds answers to.Thor's story on Earth revolves around his inability to lift his hammer, a feat he can't perform until he's deemed "worthy" by a standard he doesn't understand. His inability to articulate the journey before him affords him moments of self-reflection. Shortly after being told of his father's death, he grabs a drink with Erik Selvig (Stellan Skarsgård), during which he experiences a quiet moment of uncertainty. He's at his wits end, powerless and without a home, and he can't figure out what to do.It's a fantastic dramatic beat on its own, but Thor's lack of outlook in this moment is inadvertently shared by the narrative as a whole. Thor is an arrogant warmonger who seeks to conquer by force, and the reason he's banished is his bloodthirst and reckless militarism. These facets of his personality fall in line with Asgardian tradition, which he would likely have to challenge head on — both in his kingdom, and in himself — if he hopes to change in any substantial way.Instead, the reason he's finally able to lift his hammer is entirely disconnected from this setup.

Thor Gets His Groove Back… But Why?

When confronted by Loki's Destroyer, Thor's friends engage the metallic creature while the exiled Thor shepherds bystanders to safety. He tells Sif and The Warriors Three (Hogun, Fandrall and Volstagg) that he has a plan. He doesn't let them in on this plan, though Hemsworth's somber expression says it all: it will likely lead to his death. And it does.In what plays like the culmination of a character arc, Thor nobly sacrifices himself to save the humans in his vicinity. But this sort of gesture was never called into question during the preceding narrative. Laying down his life for someone else, especially someone innocent, never comes up during the film as something Thor is unlikely to do. Even his apology to Loki in this moment is for a reason he doesn't seem to understand. It's an apology just in case.There's little by way of action, or even dialogue, to suggest that the Thor of a few days prior wouldn't have laid down his life this way. Earlier in the film, Sif mentions wanting to die "a warrior's death." Sacrifice on the battlefield is already an Asgardian symbol of nobility, so what is Thor's Earth-bound journey really for, if this is how it culminates? Would Thor not have ferried innocent bystanders to safety, regardless of the kindness shown by Jane Foster? These are questions that don't seem to have answers. They only ever come up as answers, to questions the film never asks in the first place.Upon Thor's return to Asgard, Loki asks him why he no longer wants to kill Frost Giants, to which he replies: "I've changed." But Thor's apparent change, which came about on Earth and among a people he'd never encountered before, doesn't have any dramatic bearing on his initial battle on Jotunheim. The Frost Giants are a people Thor feared and detested because of their centuries old blood-feud, a notion that's never challenged or even mentioned during the film.Thor does, however, complete some semblance of an arc after his return to Asgard. When Loki unleashes the full power of the Bifrost (the bridge between Earth and Asgard), he aims its destructive capabilities at Jotunheim. The bridge is sure to destroy the Frost Giants, but Thor hammers away at its foundations until it breaks, cutting him off from Earth, and from Jane, in the process.This is an unboundedly selfless act, wherein Thor chooses the greater good over his personal desires. He would likely have never done this pre-banishment, given that it saves a realm at war with Asgard, but what leads him to this point in the story is still a question unanswered.There's no beat or even suggestion throughout the narrative that makes him question why he went to war in the first place. Thor's actions, while in service of saving lives (both human and Jotun), don't stem from reciprocating or paying forward any kindness or selflessness he was shown on Earth. Destroying the Bifrost still comes about through the force of his hammer, a symbol of masculine destructiveness. Thor, at least in this film, never comes around to using it the way his father suggests: as "a tool to build."Rather than any dramatized change in outlook or methodology, Thor still operates within the same archaic, masculine, militaristic paradigm. He merely shifts its target. Whatever one feels about superheroes constantly hitting things — one might argue the genre would be boring without it — by placing its character in this predicament, the film short-changes his arc.

Marvel’s Continued Hesitance

One can easily intellectualize Thor's character development. On paper, where he begins and where he ends up are two different places. It's part of what allows the film to remain borderline functional, even if it's emotionally incomplete. Thor's story, however, never follows a sound enough trajectory to feel resonant. There is no singular moment that defines Thor as a character — no "Steve Rogers jumping on a grenade" — and no difficult decision that's satisfyingly expressed.The film's plot-structure and dialogue treat Thor's selflessness as the opposite of his arrogance. However, through the film's own narrative framing, this selflessness on Earth is ultimately disconnected from his violent conquests elsewhere. When Thor sacrifices himself to save the humans, this act is entirely independent of his warmongering past. In the process, his second and arguably more important sacrifice — the decision to destroy the bridge — plays like emotional leap, since he never confronts the parts of himself that led to his banishment.Once again, Marvel's reluctance to entertain the notion of confronting military conquest works to its narrative detriment. In the first "Phase" of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, war is merely a given. It's the way the world at large operates, a status quo that has neither cause nor solution from a character standpoint, even though a character-centric approach to war is exactly what some of these films are missing. The heroes aren't allowed to truly change, because they're never made to face the parts of themselves most connected to the world around them.In the process, the early Marvel films fall just short of emotionally satisfying. Though, as with other future installments, Thor's third-sequel Thor: Ragnarok would finally address this shaky foundation, turning the God of Thunder into one of the series' most interesting characters going in to Avengers: Endgame.

***

Expanded from an article published April 5, 2018.