'Aquaman' Spoiler Review: A Big, Goofy Cartoon With Larger Ambitions

Aquaman rides a bizarre line between serious and silly. On one hand, it's a tale of environmentalism centered on a mixed-race character trying to find his place. On the other, it features Jason Momoa falling off a cliff, scored like a Wile E. Coyote cartoon. Only one of these really works.

The film's two disparate halves never quite coalesce; recent superhero movies like Black Panther and Into the Spider-Verse strike a much neater balance between tone and subject, but despite being sluggish whenever it stops to address its own relevance, Aquaman bursts to life when embracing its inherent cartoonishness. Like the film's lead character, I feel torn about the goings-on in Atlantis. However, things like meaningless trident battles and comic-derived bongo Octopi help me forget why, at least for a moment.

The New King Arthur

Zack Snyder doesn't get enough credit for casting Jason Momoa. Even prior to the character's delightful quips and chirpy battle cries — "Yeayuh!", "Awright!", "I dig it!" and "My mahn!" are Justice League's most (only?) quotable lines — Snyder presented a radically changed version of Arthur Curry in the buildup to Batman v Superman. The mixed-race Hawaiian actor, through his mere presence and before even a single second of screen time, imbued Arthur with a fresh new subtext, adding real-world cultural mythology to Aquaman's oceanic roots. (Fittingly, the Hawaiian ocean-god Kanaloa is often represented by an octopus)

When the character was first revealed, Momoa's shark-toothed 'aumakua tattoo took center stage. The family crest on the actor's forearm extended to his character's entire torso, resembling the scaly costume from the comics. Little was made of this background in Justice League — in which he sports Atlantean armour and visits his homeworld, two things Aquaman retcons — but the radical departure allowed director James Wan (Furious 7) to tell a tale of cultural belonging.

Arthur Curry has always been an outsider to Atlantis. In the comics, the character was Caucasian, and it his blonde hair set him apart. However, in casting the humanoid Atlanteans as almost entirely white, and by having Maori actor Temuera Morrison (Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones) play Arthur's human father, Wan flips the script on the character's metaphorical, in-name-only oppression, replacing it with a real biracial dynamic.

Aquaman brings Arthur's tale into our world. The character is established as Maori; his father denotes the need to finish Arthur's tribal tattoos. Every time Arthur's half-brother Orm (Patrick Wilson) venomously brands him a "half-breed," his words have a real-world sting. Arthur's mother Atlanna (Nicole Kidman) is even sent to the gallows for miscegenation, all of which sets up a superhero who feels radically different from the status quo.

That said, despite the characters constantly mentioning his background and Arthur being verbally rejected by his white Atlantean kin, the film never meaningfully weaves this subtext into its plot. Thematically, Arthur's rival Black Manta (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is even introduced through a similar lens. He comes from a line of African-American soldiers abandoned and oppressed by very the county they fought for, and he's even cast aside by the Atlanteans once he outlives his usefulness to them. This vital commonality between hero and villain is never brought up in the text, nor is it ever used for any narrative purpose; an omission emblematic of the film's many problems.

Awkward Framing

The position Arthur is placed in, as the only character who can stop an oncoming conflict, puts him in a strange narrative predicament. The sea is about to wage war on the land. King Orm wields, among other things, biological essentialism in order to annex the Altantean armies. In turn, this essentialism is the very thing that makes Aquaman the film's hero. Arthur isn't eligible for the "hero" role through racial duality. Rather, what makes him eligible is birthright — or, in the context of the film's own coding, the white side of his family.

Arthur acquires Atlantis' magic weapon — the late King Atlan's trident, pulled from his hands like a sword from stone — by claiming to protect both land and sea. However, this ascension to heroism is predicated on innate blood-worthiness. It's the primary justification for Arthur being the hero (as opposed to, say, someone born to the Atlantean underclass) and while it's similar in political structure to this year's Black Panther, Marvel's African monarchy still sees the non-royal M'Baku fighting for the throne. Aquaman, in contrast, seems to entirely preclude the idea of a non-royal ascension, a structure Arthur works his way into without question. Why Aquaman? Because Aquaman, it would seem.

King Orm's methods are rooted in adherence to tradition, and Arthur seeks to defeat him by colouring within those traditional lines. In contrast, Killmonger pulls off the same ploy as Arthur in Black Panther, but his cultural ostracizing as an African American is a key facet of the story. His goal, after all, is global Black liberation. Aquaman, unfortunately, leans more towards preserving an existing status quo both on land and at sea.

By the film's end, Arthur does little to act on the relevant qualms Orm has with the surface — humans pollute the oceans and kill their aquatic friends! — while his Wakandan contemporary, Black Panther, undergoes a radical change in outlook. One could argue the two films are apples and oranges, but Aquaman's lack of meaningful outcome is owed, at least in part, to a lack of coherent antagonist. Black Panther, having excelled at this, makes for a fitting jumping-off point.

While Orm pulls strings and jumps through hoops to control Atlantis' armies, his eventual target is the surface world, a plan to which Aquaman is merely incidental. In contrast, Killmonger's ploy involves dethroning T'Challa both out of revenge, and as a means to a military end. In Aquaman, this role is split between militaristic Orm and the vengeful Black Manta. The former drives the plot, while the latter is perfectly placed to drive a character-centric story; these two elements, however, end up mutually exclusive.

When Black Manta first offers to kill Aquaman, Orm doesn't seem to care. Manta then disappears from the film for about an hour. This disharmony between villains, and thus between plot and story, makes the film far less emotionally engaging.

Aquaman of Two Worlds

Attempting to frame being mixed race or bi-cultural as a superpower is commendable in itself. It's an instance of diversity adding layers to a pre-existing story, but it's also a story told mostly through words. Little by way of narrative function separates Aquaman from, say, the likes of Mera (Amber Heard), whose primary purpose appears to be explaining the plot to Arthur and, in the process, justifying his centricity within it. Mera however, is a fellow land-walker and royal who shares Arthur's goals. In fact, she convinces him to align with those goals in the first place, and she seems just as if not more capable.

The plot is so disconnected from Arthur's ethos that it would remain largely unchanged if Mera were the protagonist. This would admittedly be nitpicking, were it not for the fact that the central problem here is the lack of thematic follow-through. Within the film's own dramatic mechanics (for instance, the specifics that lead to Arthur acquiring Atlan's trident), it turns out to be intent and royal blood, rather than Aquaman's unique cultural outlook or life experience, that makes him a hero. This intent and blood-status are anything but unique to him, yet they're treated a one-of-a-kind facet of his identity making him worthy of the throne.

(There are actually two female characters who share these traits, but Arthur's unique position is explained away as him being "a true king".)

The hour-long disappearance of Black Manta doesn't bode well for the narrative either. As far as the film's villains go, Manta is uniquely suited to be Arthur's foil, thanks to both his family history as well a recent tragedy for which he holds Arthur accountable. Once the film sees fit to bring him back, though — Atlantean laser guns-a-blazing — it kicks into high gear despite never once touching on this potentially riveting dynamic.

For better or worse, it's amid the film's numerous, eye-popping action scenes that every aforementioned thematic shortcoming becomes temporarily moot.

Big, Dumb Fun

After the film's first screening, a friend jokingly tweeted about a scene "where Black Manta stands on a platform and swings a wrecking ball at Aquaman... the ball swings all the way around until it squashes Black Manta like a pancake." Sadly, this doesn't actually happen, but it wouldn't have felt out of place if it did.

Aquaman is a slog when it's trying to be straightforward, but on some level, it seems aware of this. Of course, this hardly excuses the inertia of scenes where characters, sans chemistry, stare at each other longingly (or discuss battle plans, or exchange personal histories), but almost every such instance — filmed with the most mundane, lifeless shot/reverse-shot coverage — feels like the drama reaching its tipping point before the film pivots at breakneck speed.

First, there's an empty romantic beat between Thomas and Atlanna. Then, an exposition roundtable involving Arthur, Mera and Vulko (Willem Dafoe). And finally, a groggy dramatic scene between Arthur and Mera on land, where it seems they're about to kiss. On at least these three occasions, the film's glum dramatic chatter is broken up by sudden explosions, as side characters in candy-coloured fish-armour burst into the frame and break up the monotony.

The film, as if suddenly interested in what its characters are upto, shifts in tone and visual approach. The static close-ups are replaced by moving long-shots. Highly choreographed fights unfold in single takes, filmed on wide lenses just slightly short of fish-eye (heh). This skews the perspective, making more of the action whiz by in a given moment, as the characters create a visual feast. They flip and jump and roll around as Wan and Don Burgess' kinetic camera matches their every movement.

The action is also the only thing connecting Arthur and Atlanna in any meaningful way beyond dialogue. In two separate scenes set decades apart, the camera whips around them as they smack Atlantean Stormtroopers with a ridiculous weapon — a quindent passed down between generations — performing super-powered acrobatics and causing general mayhem. Throughout the film, the characters constantly talk about Arthur's lineage, but the only time it's dramatized is in the mirroring of these action scenes, when the film is at its silliest.

Arthur drinks and makes merry with his father on land (he drops his first "Awright" here!), but it's vital that he be seen a moving reflection of his late mother as well. Especially in a story that is, at least nominally, about bridging his two lineages.

A Clunky Cartoon

When Black Manta finally returns to kill Aquaman, the ensuing land chase in Sicily feels right out of a Saturday Morning cartoon. Manta's henchmen plough through walls and zoom past puzzled onlookers; one aquatic villain even dunks his head in a toilet so he can breathe. Manta, now sporting enormous eye-lasers, zips around like a balloon with a hole in it; "CLUNK" sounds emanate from his oversized head every time he takes a hit. The film is waggish visual stimulation for babies, and I'm not sure that's a bad thing.

At one point, a falling church bell endangers some bystanders. Aquaman, rather than engaging in textbook heroics, headbutts it out of the way (another "CLUNK") before Mera incapacitates the remaining henchmen using telepathically-controlled wine. All of this unfolds in slow-motion, nestled between rapid foot-chases filmed with reduced shutter-angle to reduce motion blur — a jerky, strobing effect caused by reduced exposure time popularized by Saving Private Ryan — thus bringing the action closer to DC's usual crop of janky animation.

If all this sounds "bonkers," that's because it is, and it's presented in a manner befitting of the phrase. The action departs from the rest of the film by resembling a thrill ride, or a cartoon, or a videogame cut scene. King Orm, whose thinly conceived motivations create a narrative vacuum, becomes a visual focal point in the third act once he dons a mask that moves with his expressions. As if the live-action Skeletor had been granted the facial freedom of his animated precursor.

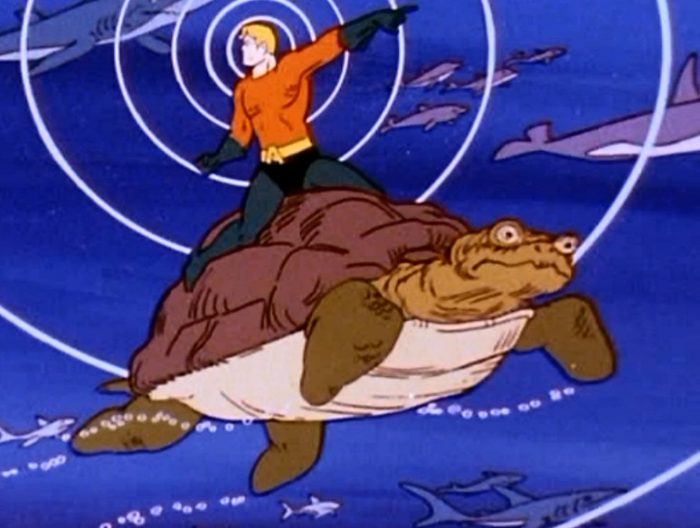

The film hits its ludicrious apex when Aquaman, now draped in his traditional orange and green, enters the undersea battle atop a Lovecraftian kraken (voiced by Julie Andrews of Mary Poppins, no less). He fights alongside adorably ugly humanoid crustaceans — all hail the Brine King! — stumbling into what feels like a renaissance tableau by way of Lisa Frank. And, in what might be the film's most overtly silly flourish, concentric circles emanate from Aquaman's head, visualizing his fish-telepathy in homage to the 1970s Super Friends cartoon:

The film is completely muddled in terms of story and theme, but Aquaman's solo arrival on the world stage takes the form of wacky cartoon throwbacks; your mileage may vary. This sort of texture often comes at the cost of story, but at nearly two and a half hours in length, there's enough story, and enough that's poorly told, that any attempt at meaningful narrative actually drags down the big, dumb action scenes, which are worth the price of admission.

For better or worse, tales of blood feuds and social messages fade into the background. In their stead, the film is rife with mermen astride whinnying seahorses and laser-toting sharks, culminating in a battle that hinges on whether or not our hero can spin his trident really fast in a circle.

Aquaman is unbearably frustrating when it's trying to be serious. At the same time, I wish the "serious" crop of superhero movies let themselves be this much fun.