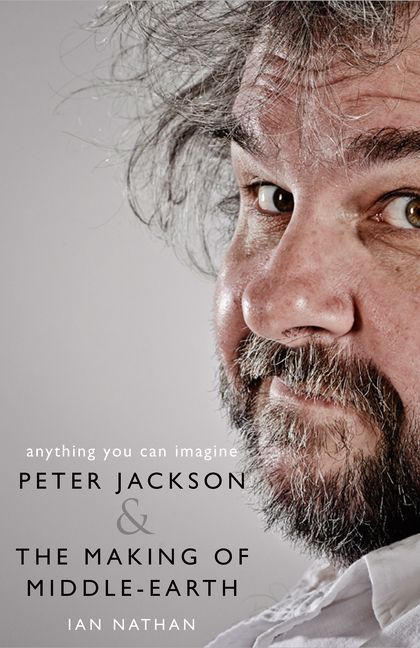

'Anything You Can Imagine' Takes Readers On A Wonderful Journey Through Peter Jackson's Middle-Earth

It might sound hyperbolic, but Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy is something of a minor miracle. Jackson and company were able to adapt J.R.R. Tolkien's epic fantasy series into three massive, all-encompassing, emotionally-driven and wholly exciting movies. The original film trilogy would end in massive box office returns, Oscar glory, and an ever-lasting legacy.

Ian Nathan's wonderful new book Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth takes readers on a journey through the films – from inception, to creation, and beyond (even the less-than-fantastic Hobbit movies are covered). We take a look at the book below, and include an exclusive excerpt.

The making of Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy is well-documented. The Blu-ray releases of the films, particularly the Extended Editions, provide hours and hours of behind-the-scenes footage, as well as making-of featurettes. With this in mind, it might seem like there's nothing new to learn about Jackson's Middle-earth adventures. But Ian Nathan's Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth proves that just isn't true. For close to 600 pages, Nathan digs deep into the films, revealing fascinating tidbits about the productions. This book truly is the definitive history of the Lord of the Rings films. Nearly every single element of the productions is covered here, from writing, to shooting, to Oscar-night jitters. Nathan's prose does exactly what you want from a book like this: it makes you feel as if you're really there, right beside Jackson and company as they pull off the seemingly impossible feat of turning Tolkien's books into an incredible film series.

It's difficult to cherry-pick particular information from such a sprawling book, but here is a snippet of interesting details revealed in Nathan's book. This doesn't even begin to scratch the surface, though.

John Boorman Almost Made a Sex-Filled Adaptation

While Peter Jackson eventually won the battle to bring Lord of the Rings to the screen, he was the last in a long-line of other filmmakers attempting to get productions off the ground. In 1969, United Artists – who owned the Lord of the Rings rights at the time – asked John Boorman, who would eventually make Deliverance and more, to helm an adaptation. Boorman had gone to UA with hopes of turning the Arthurian legend into a big, sweeping film. UA countered by saying that they owned the LOTR rights already, and Boorman should take a crack at that instead. Boorman accepted the challenge, and proceeded to script a significantly different adaptation than the books – an adaptation full of sex, including a moment when "Aragorn revives Éowyn with a magical orgasm." Needless to say, this adaptation never happened. Boorman would eventually make his Arthurian tale in the form of Excalibur.

Peter Jackson Was Almost Replaced by Quentin Tarantino

Quentin Tarantino's Lord of the Rings? It could've happened! Maybe. The early days of turning Lord of the Rings into a film series saw Jackson frequently butting heads with the infamous Weinstein Brothers, who originally had the rights to distribute. At one point, Harvey Weinstein insisted Jackson turn the three books into one movie, and Jackson said it couldn't be done – and even if it could, he didn't want to do it. Apoplectic, Weinstein demanded Jackson do as he say, or he would be fired – and replaced by Tarantino. "You're either doing this or you're not. You're out. And I got Quentin [Tarantino] ready to direct," Weinstein apparently said. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed, and the distribution rights later ended up in the hands of New Line Cinema. There's no way to know if Weinstein was being serious about Tarantino taking over, or if this was just a bluff.

Sean Astin Had Problems With The Return of the King

In the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Sean Astin delivered a highly memorable performance as the loyal Samwise Gamgee. Astin considered his Return of the King performance the best work he had ever done – and even saw potential Academy Award recognition in his future. Astin's happiness with his performance was "confirmed when he had wept his way through a rough cut during his ADR sessions in London." Afterward, Astin went as far as to tell his agent: "You know what? I think I might get nominated." Things changed, however, when he saw the final cut, and realized many of his favorite scenes had been cut out of the movie completely. Astin was so bothered by this that he gave an interview saying he felt "only twenty percent of his performance is on the screen." He immediately regretted the comment, and eventually came around to liking the film. But his reaction might have hurt his award chances – he was not nominated.

Vin Diesel Wanted to Play Aragorn

It's hard to imagine anyone else other than Viggo Mortensen playing Aragorn, and it's even harder to picture Vin Diesel in the role. But the actor really wanted to play the part. So much so that he sent in a homemade tape of himself auditioning to play Aragorn. "He was a big fan," Jackson says in Anything You Can Imagine, "but at that point we didn't know who he was, and he didn't fit our concept of the character." Yeah, I bet.

Patrick Stewart Wanted to Play Aragorn, Too

While he may look to be middle-aged, Aragorn is actually 87-years-old in Lord of the Rings. Still, the character doesn't look his age, which meant Jackson and company were looking for a younger actor to play the part. But Patrick Stewart didn't get that memo, and was very interested in playing the ranger. Jackson heard that Stewart wanted a part in the movie, and grew excited. He thought that Stewart was hoping to play Theoden (a part later played by Bernard Hill). With this in mind, Jackson met with Stewart, and during the course of the meeting, it became clear that the part Stewart actually wanted was Aragorn. Awkward.

Peter Jackson Prefers the Theatrical Cuts to the Extended Editions

In my humble opinion, the Blu-ray Extended Editions of the trilogy are the superior versions. I don't even like to watch the theatrical cuts anymore, because I feel like I'm missing something. Peter Jackson, however, things the theatrical cuts reign supreme. "The unknown factor that you can never really know is would the extended cuts have gone down so well if they were the theatrical releases," Jackson says, "and you had people sitting in the cinema for three hours forty minutes instead of three hours. Who knows? I don't really regard them as the definitive versions of the movies, but I'm happy... every time I see a review where someone says, 'Oh, this is better than the theatrical version.' I'm happy because they like the DVD version. That's a nice thing to read. But I'm too close to it. I don't really know."

Exclusive Anything You Can Imagine Excerpt

Below, read an exclusive excerpt from Anything You Can Imagine, detailing Peter Jackson landing the directorial gig. © Ian Nathan, 2018. Reprinted with the permission of HarperCollins.

***

The English Patient was dying. Saul Zaentz had pleaded with the studio that they were in the process of forging art. He had protested at their shortsightedness. And he had resorted to good old-fashioned brinkmanship. They were only weeks from shooting, but 20th Century Fox were not backing down. Fox had bought the English language rights to this expensive adaptation of Michael Ondaatje's Booker prize-winning novel for a not inconsiderable $20 million (the full budget was $31 million, including $5 million of Zaentz's own money) and were insisting it have a marquee female lead.Accepting Ralph Fiennes as the hero — if such a straight- forward term could be applied to the emotionally fraught and morally elusive weft of Ondaatje's novel — already spoke of a due deference to artistic over commercial merit. This was, they knew, a prestige project. Fiennes was so very English — although his character turns out to be Hungarian.The Second World War romantic epic came endowed with a tricky structure. It told a story within a story, gradually regaled to Juliet Binoche's free-spirited nurse, and us, by a burn-ravaged Fiennes languishing within the gorgeous grounds of a Franciscan monastery somewhere in the Tuscany countryside. His tale will sweep us all back to a Sahara on the brink of war where spies and cartographers muster and a great love affair ensues, all simmering in a grand manner not seen since the imperial heyday of David Lean. The kind of film, everyone kept saying, no one made anymore.When it came to Fiennes' romantic opposite – the fragile, conflicted, swan-like Katharine Clifton – Fox were thinking of Demi Moore, in the spring of 1995 box office gold following Indecent Proposal and Disclosure. Zaentz and his so very English director, Anthony Minghella, whose determination to steer his own artistic choices mirrored that of Peter Jackson's, had set their heart upon Kristin Scott Thomas — more traditionally beautiful, more icy and layered.Bill Mechanic, who was then president of Fox, later promised on his life that the Moore rumours were untrue. Minghella maintained that 'Demi's name was always mentioned'.Whatever the case, the fractious production had reached an impasse. Actually, that was no longer true.Fox had pulled the plug.Rallying round the desperate project, already encamped in the desert, two of Minghella's closest allies, director Sydney Pollack and producer Scott Rudin, put in a call to Harvey Weinstein, the influential co-founder and co-chairman, with his brother Bob, of the independent film powerhouse Miramax.'Harvey just stepped in and financed it one hundred percent,' confirms Jackson, who has been recounting the story as a matter of significant background.Cynical Hollywood commentators, of which there are many, suspected that Miramax was already well aware the project was faltering, with Harvey ready and waiting for it to collapse so he could swoop in and save the day.Akin to Zaentz, this was exactly the kind of project that fitted Harvey's view of himself as both Hollywood player and indie king, as well as the philosophy of Miramax as a film company: sophisticated, literary, but with mainstream potential, and Oscar-worthy, always Oscar-worthy. Spinning gold on behalf of the inevitable awards campaign for The English Patient, Miramax's gifted publicists spread a tale of the White Knight who saved great art from studio defilement.Nominated for twelve Oscars (including one for Kristin Scott Thomas), winner of nine, and making $231 million around the world, The English Patient cemented Harvey's reputation. By the mid-1990s, he was the new Selznick, but operating from New York headquarters beyond the borders of Hollywood. He wasn't the kind of studio boss who would demand Demi Moore. He understood the needs of filmmakers. He could manage big, important films outside of the studio system. He also understood the marketplace and how to reach an audience. He could finesse, and he could bully. His methods, often cutting and re-cutting problem films — landing him the nickname 'Harvey Scissorhands' — he insisted were always at the service of the film. This was how, alongside Bob, he maintained Miramax's great duality: cash and kudos.Not that it was all about literary adaptations. If Minghella was his longing, romantic Sméagol side, then Quentin Tarantino, who wanted to storm the barricades of such strait-laced tradition as The English Patient, let alone The Lord of the Rings, was his expletive-spitting Gollum.Between Miramax's multiple personalities, you can also trace Harvey's attraction to Jackson: the young Kiwi embodied that very schism. He was the director of Bad Taste, Meet The Feebles and Braindead, giddy gore hound and natural wit, predisposed never to abide by the Hollywood playbook. But then he would produce something as finely tuned as Heavenly Creatures.It is often claimed that the two poles of Jackson's filmmaking pedigree are what made him so ideal for adapting Tolkien.The English Patient had finally wrapped production in 1996 when Jackson called his long-standing manager Ken Kamins and casually asked him to find out who might own the rights to The Lord of the Rings. For a certain fee, databases can be consulted.In the litigious universe of Hollywood, it is essential to cover your back. Jackson had assumed they must be with Disney or Spielberg or Lucas. 'They would all be locked up, as they say,' he admits. 'And we wouldn't have a chance. So we really went into this with no expectations at all.'Kamins didn't take long to discover that thirty years after buying them from UA, the rights to both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings still resided with Zaentz. He might not be a Spielberg or a Lucas, but this wasn't necessarily good news. Having had his fingers burned so badly with the Ralph Bakshi debacle, Zaentz had closely guarded the rights ever since.It wasn't as if since Bakshi no one had returned to the idea of adapting one of the most popular books of the twentieth century in the intervening years; they had simply come up against the Black Gates of Zaentz's resistance.If by some miraculous chance he was to agree, says Jackson, word came back that he would want to be attached to it. 'That is just the way he was. He was a producer himself. But he tended to say no. He had done his Tolkien thing, it was a huge disaster for him, and he had lost a lot of money by the sound of it. He just didn't want to know about it.'They needed a backstairs route to the rights — a secret way into Zaentz, a chance to try and persuade him. And although he didn't know it yet, Jackson already had the perfect guide. In fact, that guide was impatiently waiting for the director to call.Within the parameters of a first-look deal he had recently struck with Miramax, Jackson was contractually bound to first test the waters on any new idea with Harvey Weinstein. And this was a staggeringly ambitious plan.'The idea was to do The Hobbit as one movie, then two movies of The Lord of the Rings,' says Jackson. 'Still as a package: you make The Hobbit by itself, if it is successful you then get to do The Lord of the Rings films back-to-back. A three-film thing.'So the initial desire had been to adapt Tolkien's books in chronological order, beginning with his first, younger-orientated Middle-earth novel: Bilbo, the Dwarves, and dislodging a fire- breathing squatter.'I could tell on the phone he was really excited right away,' recalls Jackson, not yet knowing that this conversation would change his life.The English Patient may not have yet been released but Minghella had wrought classical wonders with the strange book. Another attention-grabbing, epic production based on a tricky literary source, as directed by another of his self-styled discoveries, played right into Harvey's view of himself as a promethean, David O. Selznick type for a modern Hollywood.'Who's got the rights?' he asked.'Well, it's not going to be easy, Harvey,' Jackson warned him, 'because it is this guy called Saul Zaentz.'Jackson laughs. 'Harvey was the man who had saved The English Patient. We were talking to the right guy.'If you put it in a script it would sound corny and contrived. No one would believe a word of it, but then so much of Jackson's career has been decreed by what you would call fate.Says Kamins, 'It's the big theme for him. He has always believed that fate was going to point him in the right direction.' Jackson's manager cannot think of a single conversation in all the time he has represented him where they have sat down and discussed what he should or shouldn't do with his career. 'Peter sort of functions by his own compass — that fate will deal him the right set of cards. And in this particular instance maybe more than any other, he was proven completely right.'There are things that can be seen with the naked eye when you're trying to achieve something in the motion picture market- place and there are the things that lie hidden. You can't ever see what's going on behind the boardroom doors. The business decisions, the politics and agendas, the history, or the simple expediency that can come with good timing: all those invisible but significant factors that allow you to be able to do the unexpected. Otherwise known as fate.'Saul?!' Weinstein boomed, his thick New York vowels reverberating down the transpacific line, more excited still by the chance to demonstrate the extent of his magical largesse: the beneficent Harvey, fulfiller of wishes. 'I'll call him straightaway. He owes me a huge favour.'

***

Print the legend, and the inception of Jackson's great adventure occurred on an unspecified morning while The Frighteners was in post-production. He and Fran Walsh had got chatting about how to follow up their spectral comedy-horror. In spring 1996 things were moving for Jackson: he was now working on a Hollywood stage, with Hollywood budgets at his disposal, and to a large extent still on his own terms and staying put in New Zealand. More than ever, they needed to maintain their momentum.'So how about a fantasy film?' proposed Jackson. Something like Ray Harryhausen once made, the spectaculars he had been whelped on: no irony, but a cornucopia of fantastic beasts. Only they would use the growing digital capabilities of their own visual effects company, Weta, to conjure them up rather than the chronically slow minutiae of stop-motion. Perhaps, Jackson suggested, something more classically swords and sorcery than the Arabian Nights or Greek myth that had been Harryhausen's metier. He searched the air for an equivalent. . .'Something like The Lord of the Rings.'At that point, he had still only read it the once, when he was eighteen. It was simply what sprang to mind.'Well,' Walsh replied, 'in that case why not do The Lord of the Rings?'Except it didn't go like that. Not exactly. The reality behind the decision to attempt Tolkien was a lot more complicated and painful. The river of fate had many twists and turns to negotiate.