'Akira' Turns 30 And It Remains Essential Sci-Fi And Gateway Anime

At the very beginning of Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo's landmark anime feature, the date "1988.7.16" appears on screen as the camera traces a long metropolitan expressway up through a vast urban sprawl to where a cluster of Tokyo skyscrapers is visible with Mount Fuji in the distance. Suddenly, everything is enveloped in an all-consuming white blast.

That's the effect the movie itself would have on pop culture. 30 years ago today, Akira helped introduce the Western world to anime and beyond the oft-cited laundry list of film and television properties it influenced in Hollywood — The Matrix, the Star Wars prequels, Chronicle, Looper, and Stranger Things being among the more notable examples — the movie also predicted the real-world site of the 2020 Summer Olympics.

Saddle up on your futuristic red motorcycles and let's take a look back at Akira on its 30th anniversary. Spoilers follow for one of the greatest science fiction and animated films of all time.

Outlets like IGN and Time Out have indeed lauded Akira as one of the greatest animated films, period, but it's also a film that brought increased visibility to an important sub-genre of animation. That sub-genre dated back to the early 20th century, with various anime short films pre-dating Disney's Steamboat Willie and the first full-length anime feature coming a few years after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

If every anime fan has his or her own gateway anime feature, however, then Akira is perhaps the original gateway anime feature, the one that really opened up the floodgates and exposed the U.S. market to a new wave of '90s anime like Ghost in the Shell. Akira actually hit theaters three months to the day after Studio Ghibli's My Neighbor Totoro, another anime classic, but it was not until the late '90s that Ghibli would start earning the same recognition in the U.S. with films like Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away.

Like many Westerners, Akira is one of the very first anime films I ever saw and when I watched it, Tokyo wasn't even a twinkle in my eye. I had no idea I would later move there, marry a Japanese woman, and make the metropolis my home. But there you go: that's the story of my life. I was in college in the U.S. when a friend of a friend introduced me and my roommate to anime through Neon Genesis Evangelion: Death & Rebirth and The End of Evangelion. Needless to say, my mind was sufficiently blown and I began seeking out other anime titles.

Akira's reputation preceded it, but nothing could have prepared me for the dynamic cocktail of weirdness that the movie offers up. This is a film where biker gangs run afoul of super-powered children with decrepit faces. It's a film where an inanimate teddy bear comes to life, crawling up over the side of the bed before disappearing and reconstituting itself as a lumbering monstrosity that now looms over the bed and oozes milk from every pore.

That's not the movie's only nightmare scene. It's also a revenge fantasy where teens named Tetsuo become totalitarians with tentacles. The central relationship between Tetsuo and his friend Kaneda, who grew up in the same children's home before taking to the streets as members of the same biker gang, provides the linchpin for the movie's character drama.

In his red biker jacket with a capsule on the back of it, Kaneda is the epitome of teen coolness, a guy who leaps into action and drives a motorcycle that has inspired real-life replicas. At the beginning of the movie, that motorcycle guides us through the streets of Neo-Tokyo, accompanied by what The Japan Times called "pulsing polyrhythmic percussion."

Otomo reportedly commissioned a soundtrack from composer Shoji Yamashiro hinged on two moods: "festival" and "requiem." The background chorus, for instance, of "Rassera, rassera," during Kaneda's musical theme is a real chant that can be heard at street festivals in Japan. At the time, Akira was the most expensive anime ever made, and it's significant that this movie built its vividly realized world from the sound up, recording dialogue and music and then synching hand-drawn animation to that foundation of sound.

As a villain, Tetsuo is terrifying. He starts out envious of Kaneda, wanting to take his movie-star motorcycle for a spin, later fixating on it as a kind of trophy or status symbol that is worth the life of one of his old friends. Like Dane Dehaan's self-styled "apex predator" in Chronicle (a movie that was greatly inspired by Akira and has been called the American Akira), Tetsuo goes from being weak, bullied, resentful, and subservient to his alpha-male friends to being all-powerful and godlike, capable of taking on tanks and flying up into space. He's the fanboy turned fascist, one who literally wraps himself in a red cape and ascends a throne amid the rubble of his telekinetic rampage.

As noted on StarWars.com, another comparison for Tetsuo, the petulant man-child overwhelmed by power ("Unlimited power!") would be Anakin Skywalker in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith. Like Anakin, Tetsuo is in touch with something — a Force, you might call it. "Akira is absolute energy," the movie tells us. "Akira's power exists within everyone." It's a mystery beyond all human reason that just might represent "the next stage of human evolution."

What sets Tetsuo down the dark path is that the power he has inherited is to him as a human's power would be to an amoeba. So it is that Akira goes from phantasmagorical hallucinations where Tetsuo's insides are spilling out to full-on body horror, as Tetsuo morphs into an amoeba-like mass, sending out pseudopods to devour everything around him. In the end, he actually births his own explosion of life in a pocket universe, much like Akira would do with '90s anime.

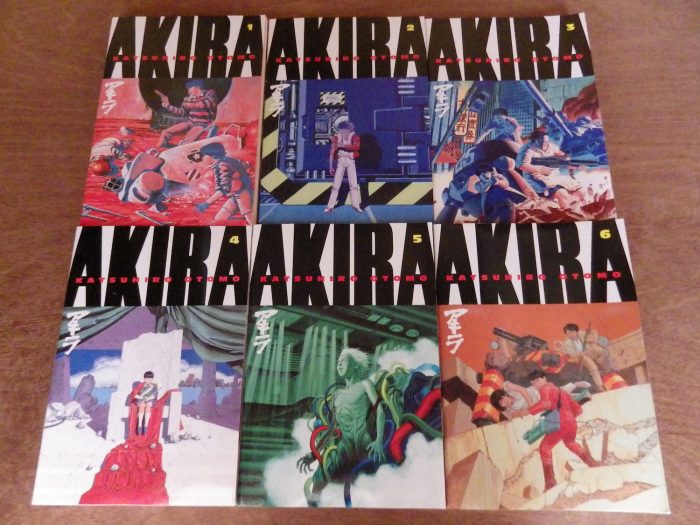

The film's cyberpunk trappings help make it more accessible to sci-fi-loving Westerners, but even after I made the move to Tokyo — even after I consumed all six volumes and 2,000+ pages of Otomo's original comic (my first manga experience) — the movie kept peeling back to me in new layers that I hadn't even realized were there.

I was completely ignorant about the film's tentacle porn influence, for example. One of my new co-workers pointed it out to me and I was like, "Uh, what's tentacle porn?" I didn't even realize that was a thing. Though of course, anyone who's seen the late Anthony Bourdain's Parts Unknown episode on Tokyo may recall Bourdain sitting down with manga creator Toshio Maeda, the so-called "tentacle master." Legend of the Overfiend, the anime version of Maeda's twisted erotic horror manga Urotsukidoji, had released its first two chapters prior to Akira, touching off a modern revival of the disturbing, phallocentric imagery of The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, the 1814 Japanese woodblock print by the Edo-period artist Hokusai (who influenced Pablo Picasso, among others).

That's just one bizarre example of the many layers this movie holds. On my most recent rewatch, one of the scenes that stood out to me the most in Akira was the one where the corrupt politician, Mr. Nezu, is lugging his overstuffed suitcase full of money and documents through an alleyway as the city descends into martial law. A ghost from his past comes walking out of the shadows: it's Ryu, the resistance fighter and true believer he just shot and betrayed before fleeing with his suitcase.

Mr. Nezu drops the suitcase, it pops open, and the papers are scattered to the wind right before he crumples over and suffers from a heart attack. Leaking blood down to his boots, Ryu staggers on by him and sinks to his knees at the end of the alleyway, his dream of revolution playing out like a nightmare in front of him as chaos unfolds in the streets. It's the culmination of an almost superfluous subplot, yet it's rendered so powerfully that it justifies itself as a microcosm of individual lives caught up in the blood-red tide of sudden change.

This really only scratches the surface of Akira. While we've been celebrating the 30th anniversary of Die Hard here on /Film with a series of articles, newspapers in Japan have been celebrating #AkiraWeek with their own series of articles. These two 1988 films obviously inhabit different genres, but Akira is arguably a movie whose sphere of influence extended outward from Japan to where it now takes up the same psi-blast radius as Die Hard.

Consider the fact that Akira helped inspire the bullet time effect in The Matrix. Some of the film's animators have since gone on to work for Disney and Ghibli and to contribute to films like The Animatrix, Kill Bill, Vol. 1, and Batman Ninja.

Right now, construction is underway on a new Olympic stadium in Tokyo like the one that serves as the setting for the movie's memorable climax. Over the years, Hollywood has tried (as yet unsuccessfully) to mount a live-action remake of Akira, with Taika Waititi being the most recent director attached to the project; but unless it can be done with the same finesse as, say, Jon Favreau's live-action remake of The Jungle Book, there's almost nowhere to go but down in terms of quality. Dense, enigmatic, sometimes confusing, but never less than imaginative, Akira set a new high bar for animation and science fiction that very few films are capable of touching. As they say in the movie, "Long live Lord Akira."