Beyond The Infinite: Revisiting '2001: A Space Odyssey' On 70mm

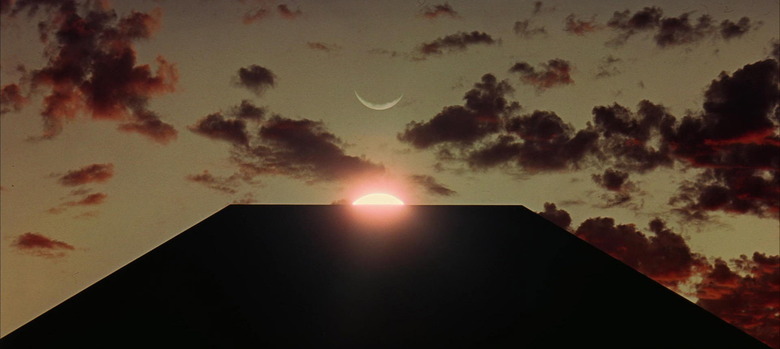

Primitive humans, caressing a consummate altar, worshipping, perhaps for the first time. We worship with them. Manmade celestial bodies, waltzing to Johann Strauss II, a flawless union of past and future. We waltz with them. A chilling cyclops, made of ones and zeroes, who ought not to feel human. He does. His victims, flesh and blood, ought to, but feel distant.

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey is a journey through space and time and perception, and it remains the quintessential celluloid experience. More pertinently, it's a communal experience, as most great cinema tends to be, eliciting gasps and applause and nervous laughter from even the most familiar viewers, and it recently made its return to theatres on its 50th anniversary.

At the 2018 edition of the Cannes Film Festival, The Dark Knight director Christopher Nolan presented the world with what he called an "unrestored" print of 2001. The film has played in theatres numerous times over the decades via, among other means, 2K digital scans and touched-up 70mm prints. Nolan however, whose own Interstellar draws heavily from the film, curated this new copy himself from Kubrick's original camera negatives.

Nolan is a known proponent of the continuation of celluloid – he recently assisted with the re-opening of Kodak in India – and his support for the medium is not without reason. As his own recent works have shown, at least for those lucky enough to have watched them on 70mm (or even 35mm, once industry standard), the film medium, when used correctly, tends to be leaps and bounds ahead of digital when it comes to the aesthetics we associate with the "cinematic." The overall comparisons are certainly a longer debate; exceptions exist, and digital tech has been fruitful for those not simply trying to imitate film – the likes of Scorsese, Cameron, Soderbergh and even Jean-Luc Godard – but there is perhaps no better sampling of film's continued prowess than Kubrick's space-set masterpiece.

While the widespread move to digital has gone uncommented upon by the vast majority of moviegoers, a return to watching movies on film at revival screenings and the likes brings with it a certain set of expectations, especially for older works. A battered print, for instance, feels like it's lived a life. I recently had the pleasure of watching Wong Kar-wai's Happy Together (1997) on 35mm. It felt like re-discovering a lost relic. Rather than seeing the images re-created through combinations of red, blue and green pixels – the yellow you see on digital isn't really yellow – this twenty-year-old film print reflected, almost exactly, what was once placed before it and what had since been seen by so many others over the decades. Like an antique mirror, frozen in time.

In the case of 2001: A Space Oddysey, this reflection – quite literally; processed film contains silver – is the past's version of a bright and terrible future, beamed to us in the present.

Seeing Through the Eyes of Celluloid

We see, mirrored in this "unrestored" vision, every minute detail of the film's lavish space stations. We see the landscape of the pre-historic "Dawn of Man" section beat with both an Earthly warmth and the projector's own flicker – the projectionist, who personally introduced the film at New York's Village East Cinema, took a few moments to get things right – a reminder of both the physical images rolling at 24 frames per second just above our heads, and of the human effort necessary to calibrate them in an era where movie screenings run on timers. As with most things shot on film, projecting these images as such yields vibrancy, clarity and tangibility, allowing us to peer directly into what cinema once was.

The movie itself remains a curious masterwork, enhanced by a canvas that sucks in any viewers who pay it enough attention. The space-station hallways, adorned by people and details and a sense of purpose, envelop. Space itself, with a depth unmatched even by most 3D, envelopes even further. As light bounces off Kubrick's spaceship models, each rotating as if weightless and detached from concern, we may as well feel the sun on our cheeks, as the satellites become ballroom floors for the "Blue Danube." They expand and contract as shadows move across their surface, shifting in size and shape but maintaining a constant allure – though light illuminating the tangible, the technological and the futuristic, is a versatile concept in Kubrick's hands. It doesn't always come off as heavenly.

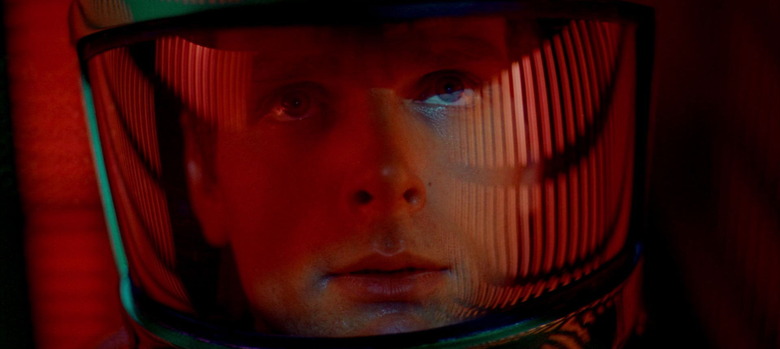

The four-armed space pods, which become humanoid avatars for the villainous HAL 9000, float ominously, backed by nothingness as their surfaces become garish. There's almost too much light reflecting off them, a contrast against the infinite darkness. The very concept of visual contrast, between light and dark, is distinctly enhanced by the physical medium. The red of HAL's solitary eye is more hellish. The cacophony of colours hitting the face of a stranded Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) make his close-ups nightmarish, as his cold, hard stare begs us to search for the fear we're already feeling as Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) tumbles through the void.

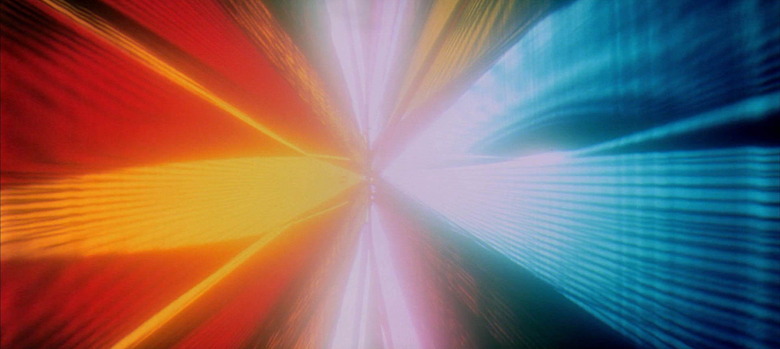

When Dave finally flies through the "star gate" – a sequence that, in 1968, required special effects to be burned into the film's very fabric – he is transported, as if towards some unquantifiable answer about what lies beneath the surface of existence. The incorrectly shaded landscapes, like skewed memories, fit uncannily into this montage, a series of sounds and feelings captured as colours, as if unraveling the layers of space and time as we see them. On the biggest, clearest and brightest canvas, 2001: A Space Odyssey allows one a unique opportunity. Rare is the experience of not only watching a film, but falling into it, allowing it to transport you elsewhere. To a place – and feeling – seldom expressed in words.

The Lost Art of the Event Film

The whole world coming out for the latest superhero or Star Wars film is certainly a sight. Today's big-budget, border-transcending blockbusters are simple enough to be understood by anyone, anywhere. Which isn't a slight, mind you – I enjoy the Marvel movies myself – but modern space outings are, by and large, a far cry from Kubrick's 2001. If this fact is lamentable, it's lamentable only because thought-provoking, abstract science fiction has been rendered a mainstream rarity. Annihilation, for instance, received theatrical releases only in three countries. Though notably, what separates 2001 from its large-scale contemporaries isn't just its abstract nature, but its presentation.

The intermission is all but lost in the United States. Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight is the only major example in recent memory, and even countries that do still have intermissions (like India) have them whether or not films actually call for a break, so that theatres can sell more popcorn. Ironically, profit is the same reason Western cinemas refuse to incorporate intervals, as this allows them to pack in more screenings per day. The event films of America's past – Biblical epics like Ben-Hur and The Ten Commandments, or David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia, running at nearly four hours each – treated their respective structures like the opera. 2001: A Space Oddyssey followed suit, and still does at most screenings today, opening with an overture played over a blank screen – or closed curtains, depending on the cinema. But 2001 also stands far apart from its contemporaries in the exact nature of its intermission.

Ben-Hur and Lawrence of Arabia, whose intermissions were born out of length and thus necessity, featured grandiose, original orchestral arrangements as re-introductions to their seconds acts. Audiences were welcomed back with a sense of pomp and circumstance. Kubrick's 2001 however, at a mere 142 minutes of running time, opts for the daunting sounds of György Ligeti's "Atmosphères," a promise of something profoundly unnerving. Music from the 1961 opera not only opens both acts, but can be heard as Dave Bowman flies through the "star gate," as if the audience is being primed for the beginning of some rattling new tale, a mysterious third act, towards the end of the saga.

2001 in 2018

The film's final segment sees Dave Bowman trapped in an uncanny, neoclassical dwelling. Even on a ninth or tenth theatrical viewing – as is the case for this writer – the film's "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite" segment is the payoff to re-experiencing two hours of the literal and the familiar. The images of this final act never change, but their meaning is predicated on what one brings to the preceding story on a given day, not to mention what one brings to this section itself. An understanding that often changes as our own understanding of the world, and ourselves, evolve through experience.

Viewers today are arguably more attuned to discerning meaning from moving images. It's a byproduct of our media-saturated landscape, a status quo that also brings with it a new understanding of technology. The tech seen in 2001, from Skype calls to iPads to artificial intelligence, is far more reality for us than it is science fiction. It's reflection of who we are, rather than who may become. HAL's "unplugging," for instance, feels more and more like the death of a living being as we move forward, into a world where the nature of consciousness shifts towards the digital.

None of which is to suggest we're now able to unpack literal or exact meaning from the film's final act, of course. Even 50 years on, Dave watching himself age – passively at first, before the camera shifts to an older Dave's point-of-view – remains an unparalleled head trip. What Dave sees when he enters the "star gate," or what his apparent post-mortem enlightenment represents, are questions that will never be answered, though they will certainly be pondered for years to come.

No matter how attuned audiences get to finding definitive answers, or how attuned modern filmmakers become at creating puzzle boxes to be solved, 2001: A Space Odyssey will likely remain the most potent distillation of Kubrick's directorial mantra: "A film is – or should be – more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. The theme, what's behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later." The film's eerie musicality, equal parts unsettling and alluring, will continue to enrapture audiences every time it returns to cinemas.