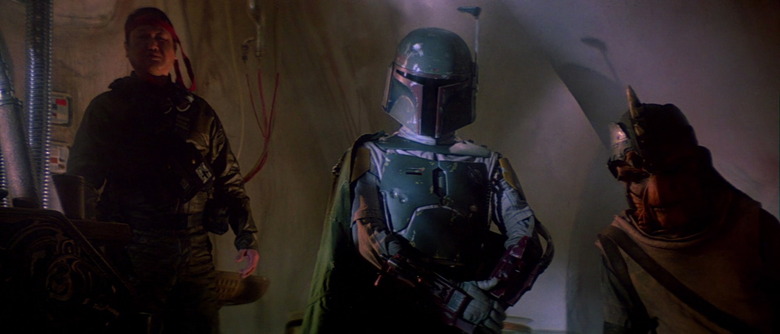

James Mangold's Past Movies Make Him An Inspired Choice To Direct A Boba Fett Film

It's the movie news that demanded an emergency podcast last week: Boba Fett is apparently locked in for his own Star Wars spin-off, to be directed and co-written by James Mangold. The Fett film had long been rumored, so for many fans, the bigger surprise probably came from seeing Mangold's name attached to the project. However, the news makes perfect sense if you consider Mangold's filmography.

It may not be outwardly apparent just from scanning the list of movies he's made, but when you focus in on his best work, it becomes clear that Mangold is a filmmaker who draws great inspiration from a genre whose heyday has largely passed: namely, the Western. If the American Western is a fable in the same way that Star Wars is a fairy tale, then throughout his career, Mangold has consistently been able to reimagine that fable in new film settings. This is what makes him such a good match for a space western about everyone's favorite Mandalorian bounty hunter.

The bygone genre of the Western is not the only muse that Mangold keeps returning to in his work. If you had to sum up the overarching theme of many of his films, you could say that they demonstrate a recurring interest in the human frailty behind the veneer of legends.

Whether it be a Civil War veteran forced to live with the lie of how he lost his leg, or a local sheriff who once saved a girl from drowning at the expense of his hearing and career ambitions, Mangold's protagonists are often down on their luck and in need of some saving grace. In 3:10 to Yuma, this principle was distilled down to a single quote: "Sometimes a man has to be big enough to see how small he is."

We've seen enough prequels already. How cool would it be if the Boba Fett movie actually took place after Return of the Jedi and followed the broken bounty hunter as he crawled out of the Sarlaac pit — all scarred up — and used his wits to survive and reestablish himself in the Star Wars underworld?

Cop Land

Cop Land saw action star Sylvester Stallone playing against type as a town sheriff who is deaf in one ear and forty pounds overweight. This was only Mangold's second feature, but for his first studio film, the young writer/director was able to wrangle an all-star cast of tough guys that included Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, and Ray Liotta.

"Urban western" was the term used to describe Cop Land. It's easy to see why: the film is essentially High Noon set in New Jersey, with the fictional town of Garrison functioning as a modern suburban frontier for corrupt New York cops and their families. Substitute the Star Wars galaxy for this place and let Boba Fett navigate it and you might have the makings of an intriguing cross-genre flick. In a making-of featurette, Mangold even delivers a telling quote that shows how you could fill in the same template with planets and characters from the Star Wars universe:

"I had this idea in my head that I wanted to make a western. And yet I didn't feel like I was really capable in some ways of writing a period western—you know, a Montana, Texas, western. So I thought about things I knew and how places I knew and people I knew would somehow work in that kind of structure."

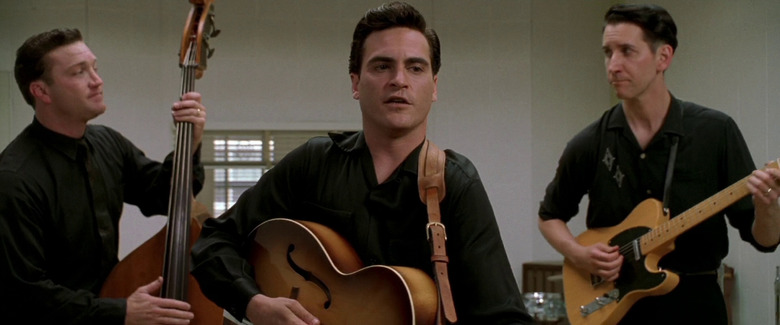

Walk the Line

Before he tackled a straight-up western with 3:10 to Yuma, Mangold would dabble further in some of the genre's tropes with Walk the Line, his biopic about country music legend Johnny Cash. Instead of the Old West, it's the life of Cash that gets mythologized in this film. Vulnerable to drug addiction, the Man in Black cultivated an outlaw image with his prison songs, some of which he performed in front of real California inmates for the live album At Folsom Prison.

In the movie, that concert frames a behind-the-music narrative, in which Joaquin Phoenix plays Cash and uses his own singing voice to perform Cash's songs. Reese Witherspoon won the Best Actress Oscar for her spunky portrayal of June Carter, whose conflicted feelings over falling in love with Cash inspired the hit song "Ring of Fire." It's a career-best performance and the diegetic music in this film is as much as a triumph as the Cantina Band's was in Star Wars: A New Hope.

Maz Kanata's castle in The Force Awakens and the Canto Bight casino in The Last Jedi both chased the Cantina Band, but if there's anyone that could make the performance of music in-universe feel organic to Star Wars again, it would be the director of Walk the Line.

3:10 to Yuma

Rewatching 3:10 to Yuma, Mangold's top-tier remake of the 1957 Glenn Ford western, it struck me how the film shares some thematic resonance with The Last Jedi (spoilery allusions through the end of this section). Both films involve men who look back on their lives and see a legacy of failure, but who make it their dying act to become a legend so as to inspire the next generation.

Here again, we see a disabled hero: Christian Bale's one-legged rancher, Dan Evans. This time, however, he's juxtaposed against a cheerfully amoral anti-hero, Ben Wade, played by Russell Crowe. Wade is a stone-cold killer who has no compunctions about gunning down members of his own gang or brutally stabbing a taunting captor to death even though it serves no utility as far as escape goes.

This character is the closest analog to a Boba-Fett-type figure in Mangold's filmography. Bale gets his High Noon showdown like Stallone, but in a lot of ways, it's Crowe's movie. It's very easy to imagine Fett gliding through a space western the way the resourceful outlaw Wade does in this film.

The Wolverine

After an uneven run of X-Men movies in the 2000s, it was encouraging to see franchise star Hugh Jackman get a fresh start in 2013 with The Wolverine. This was Mangold's first foray into superhero filmmaking but for most of the movie, the usual trappings of that genre take a back seat as Wolverine is uprooted to Japan.

While The Wolverine is not perfect (the most common criticism being that it suffers from typical third-act superhero movie problems), it did serve to disentangle Wolverine from the X-Men imprint, letting him strike out on his own in a self-titled feature where he could play the foreign adventurer in Japan like James Bond in You Only Live Twice.

And though it cycles through a sort of "Cool Japan" laundry list (neon lights, yakuza tattoos, pachinko parlors, bullet trains, love hotels, chopstick etiquette, and ninjas clad in black), Mangold actually regarded The Wolverine as a western set in Japan but inspired by Clint Eastwood films like The Outlaw Josey Wales. This can be felt in the way Wolverine starts out the movie mourning the loss of the love of his life and all he once had.

A man he once saved from the atomic bombing of Nagasaki likens Wolverine to a ronin, a samurai without a master. That's the exact archetype Boba Fett was based on, except that he leans more toward what Lawrence Kasdan called "the bad samurai," like Unosuke, the gun-wielding character in Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo. If the Boba Fett film did take place after Return of the Jedi, it would put the bounty hunter in an interesting place where his former master, Jabba the Hutt, was dead and he was now a true ronin.

Logan

Loosely adapted from Mark Millar and Steve McNiven's "Old Man Logan" comic book arc, Logan is the only superhero film to be nominated for an Academy Award in a writing category. This film raised the bar for the genre in the same way that Heath Ledger's posthumous Oscar win for The Dark Knight did. It was one of 2017's best films and is easily Top 10 material in any consideration of the greatest comic book movies.

Pondering Logan, it's really something of a miracle that Mangold was able to upend the safe, slick superhero film formula and deliver an R-rated movie with mortality on its mind. The Wolverine suppressed the title character's healing ability and in Logan, we see it weakened again by age as he is left to care for a frail, 90-year-old Professor X, who now suffers from dementia. Johnny Cash's cover of the Nine Inch Nails song "Hurt" plays over the closing credits, a reminder of the devastating music video that depicted a showbiz legend, now an old man, looking back on his "empire of dirt."

While Steven Spielberg may have predicted that superhero movies will go the way of the Western, they're all the rage right now. With The Wolverine and Logan, Mangold was able to deliver two atypical superhero films that played upon the conventions of samurai movies and the Western, two genres with a long and fascinating interplay between them that continues to be seen on-screen. Logan directly telegraphed its Shane influence by quoting from the film and showing it on TV in a casino hotel room, where Logan angrily waves an X-Men comic and says, "You do know they're all bullshit, right? Maybe a quarter of it happened, and not like this."

Like Wolverine, whose origin went unknown in the comics for many years, Boba Fett is a character with an air of mystique about him. With the artistry on display in Logan, there's never been a better proof of concept for a movie that could explore the man behind the Mandalorian mask.

A Genre Chameleon

Ron Howard's role as the replacement director of Solo: A Star Wars Story has prompted some interesting discussion recently about journeyman directors and the value of reliable filmmaking. While the term "journeyman" has a negative connotation and I hesitate to affix that label to a director who has shown himself capable of such stellar work, I would concede the point that Mangold is one of those directors like fellow Star Wars hiree Jon Favreau who can move between genres and even deliver genre-best films without necessarily having an overbearing style that marks his output visually. As Mangold himself put it in an essay about Shane and its director George Stevens (who also helmed such classic films as A Place in the Sun and Giant):

"Versatility can be a liability in Hollywood as it is much more fashionable to brand yourself as a master of one genre or another. But that denies a filmmaker the lessons each genre can teach us about the other."

Like Favreau, with his jazzy, light-hearted style born out of improvisational comedy, you could argue that Mangold does have a specific voice as a screenwriter that shines through his films. The lessons of those films might make him ideally suited to deliver something memorable with the Boba Fett movie, the same way he did with Logan or Sam Mendes did with Skyfall. Yet unlike, say, Josh Trank, who was previously rumored to be attached to the project, Mangold is not untested nor so much of an artiste that he would run the risk of getting canned by Kathleen Kennedy.

With Star Wars falling under the Disney hegemony now, every new movie is as much a commercial venture as it is an artistic venture. While a more diverse or universally agreed-upon "auteur" filmmaker might constitute a handsome prospect for cinephiles dream-producing films in their own minds, Mangold is at least a director with the chops to maybe rock the Star Wars boat without completely capsizing it. He's a genre chameleon, capable of blending his own interests with varied subject matter. And with all the quasi-westerns he's made, letting him hang his hat on a space western is a no-brainer.