The Queer Immigrant Documentary 'Abu' Offers Cinema As Self-Portrait [New York Indian Film Festival]

Filmmakers are adept at the art of disguise, especially when it comes to their own stories. Sometimes it merely involves a change in name and location – Richard Linklater's Before Trilogy is premised on the director's real-world romantic encounter – though sometimes it involves experiences being filtered through a lens of genre. Loneliness tone-poems Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola) and Her (Spike Jonze), for instance, arguably reveal themselves to be companion pieces on the duo's failed marriage when viewed back-to-back.

There's no better visual exploration of this facet of storytelling in recent years than Tom Ford's Nocturnal Animals. Ford's sophomore effort sees author Edward Sheffield (Jake Gyllenhaaal) deal, perhaps pettily, with the emotional trauma of witnessing his wife's infidelity through a car windshield. Sheffield pens a rural rape-revenge novel in which protagonist Tony Hastings (also Jake Gyllenhaal) witnesses physical trauma through a similar window. While Ford's film cuts incisively at the often-juvenile heart of this disguise and its misuse by many straight male storytellers, the film's early moments also feature a closeted gay socialite (Michael Sheen) walking around in the ill-fitting visage of a heterosexual. Disguise, as Ford posits, isn't just a storytelling tool, but a necessary mechanism for survival. What then, one wonders, begins to take shape when a filmmaker strips away both the secret language of visual narrative – an often obfuscating cipher – as well as the walls guarding the secrets of their own life?

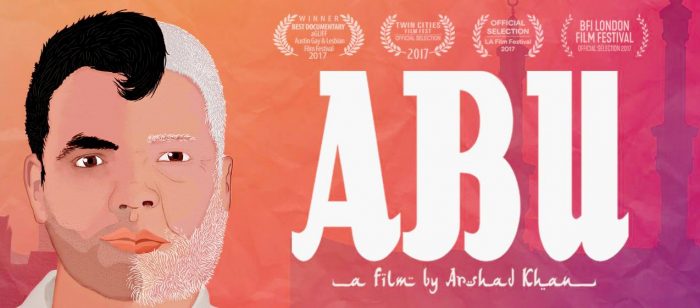

Arshad Khan, director and narrator of Abu, is all too familiar with hiding in plain sight. A gay man from a conservative Pakistani background, his family immigrated to Mississauga, Ontario in 1991 when Arshad was just sixteen – too young to have found his footing yet, but too old for a childhood do-over. The film itself comes packaged as a first-person tale about a boy and his father. "Abu" is a loving term for fathers in Urdu, and the film features "Papa Kehte Hain Bada Naam Karega" ("Father Says I Will Make Him Famous") from Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, the rare Bollywood father-son songs, immediately following its haunting animated opening. However, Abu spans the breadth of a lifetime of experiences, both personal and collective, both hilarious and heartbreaking, as Arshad Khan bears his soul via lyrical voiceover and personal home videos spanning several decades. Abu is an all-encompassing film about love, and loss, and heartbreak. A film about leaving home, finding yourself in a new land, and yearning for what you left behind. A film about 9/11, about bigotry, about fundamentalism. About abuse. About LGBTQ rights. About anti-war activism. About art, about brothers, about sisters, and about oh so much more. It's a film about every one of these things, each given its due, but it's still – as the title suggests – rooted in a complicated dynamic between a father and son. The tapestry of a life lived, and a relationship shared. Pain inflicted, and wounds forgiven. All portrayed daringly, personally and honestly, in what can best be described as a display of courage through cinema.

Abu is an all-encompassing film about love, and loss, and heartbreak. A film about leaving home, finding yourself in a new land, and yearning for what you left behind. A film about 9/11, about bigotry, about fundamentalism. About abuse. About LGBTQ rights. About anti-war activism. About art, about brothers, about sisters, and about oh so much more. It's a film about every one of these things, each given its due, but it's still – as the title suggests – rooted in a complicated dynamic between a father and son. The tapestry of a life lived, and a relationship shared. Pain inflicted, and wounds forgiven. All portrayed daringly, personally and honestly, in what can best be described as a display of courage through cinema.

The film is as close a re-creation of the self as cinema can be. Home videos and family photographs populate the near entirety of its runtime, but its foundation is the life of the filmmaker's father. His military background, his businesses (both failed and successful), his marriage, his migration to Pakistan after its bloody post-independence partition from India, and his turn towards religious fundamentalism upon moving West. These are the forces that made Arshad Khan's father. And, through a cultural, generation tug-of-war, they made Arshad Khan too.

To review Abu would be akin to reviewing its creator. The film's post-screening Q&A at NYIFF featured a strange question from an audience member ("More of a comment, really") that boiled down to unsolicited criticism of the film's use of Bollywood clips and music. Arshad's response was simply to re-enforce the context of the borrowed material, making explicit the subtext of their use. Movies that have a specific emotional place in the global South Asian zeitgeist. Songs that talk about dreams, about love, about family, or perhaps even a track that was playing during an important experience, like young Arshad professing his feelings to a friend for the first time. There's never too much of an author in their work for it to be critiqued, but in the case of Abu, what's being critiqued is a thoughtful re-creation of Arshad's very essence, painted with the finest of brush strokes, bleeding with his love and understand of cinema, culture, and finally, himself.

Meeting Director Arshad Khan

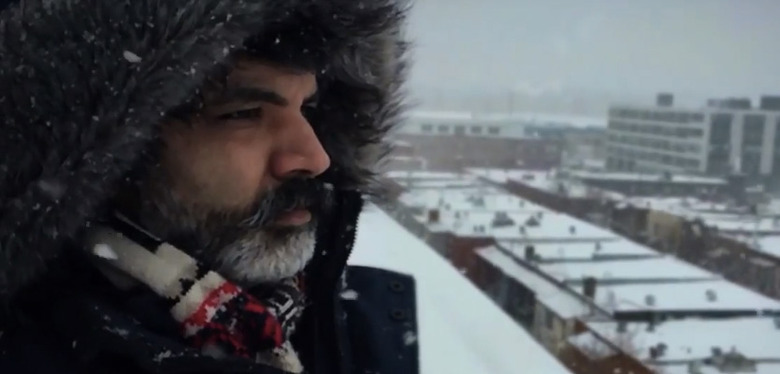

I met Arshad at the New York Indian Film Festival's opening night gala. We were seated at the same table, which meant he was separated from his friends, but he was all too happy to make conversation. That is to say, he was all too happy to scold me for filling up on bread before dinner was served, and for not eating every single vegetable on my plate once it had been. We'd known each other about forty-five minutes by this point. Arshad is playful and casual, in a familial sort of way, and was very apologetic when he returned to our table without grabbing me a drink from the bar (I didn't ask for one).

Arshad is a film programmer based in Montreal, and he was part of this year's NYIFF jury as well – not for the documentary section, in case you were wondering. Four of the five days I saw him at the Festival, he was sporting a brown leather jacket on top of a different t-shirt bearing the poster for his film; on the fifth day, the night of his premiere, he wore traditional South Asian garb. The illustrated image on his t-shirts featured half his father's face alongside half of his own, two parts making up a whole that he finally seems comfortable with. Over the course of the film, what becomes clear is that getting to this place of comfort, both with himself and with his father's place in his life (and vice versa) was an arduous struggle.

Arshad seems like a generally happy person. He's warm, and always willing to doll out hugs, but this warmth and happiness hasn't always been his default setting. Abu covers several decades of his life and delves into difficult territory, from his thoughts of suicide to the sexual abuse he endured as a child. Though as he elaborated in his post-premiere Q&A, talking about it to someone helps, and he was more than willing to recommend resources after the event.

The film is sweet and charming and difficult. It's like walking into a museum dedicated to every facet of a complete human being, and on display are the various points of inception that helped create their present incarnations. Their pain. Their joys. Their childhood interests, and the silent disappointment of their loving parents. My plan, admittedly, was to catch Abu via a private screener link and watch one of the other films playing during its Thursday night slot. Arshad however, convinced me to catch it with a crowd. He had an inkling that I'd love the experience. I'm glad I listened. Not only was I able to look over at Arshad's own responses to the film two rows down – his laughter at his once bleached blonde hair, and his quiet vindication as he got some deeply personal details off his chest – but I was also able to sense the recognition of experience amongst the largely South Asian audience.

South Asian families in the West and elsewhere tend to be part of a culture of silence. The unspoken, whether anger or abuse or even the desire for forgiveness, often remain as such until confronted decades later (if at all). Abu feels like these emotions and experiences being given a voice. Its personal moments get deeply personal, with footage from behind closed doors that feels like it ought to require familial constant (which Arshad got). What's more, the decades-long journey it takes – from the Khan family's Canadian migration, to their post-9/11 fracturing as some turned to westernization, or activism, while others turned back towards their traditional roots to deal with the isolation – is focused entirely on coming to a common understanding.

Unfortunately, all copies of Abu don't come with a bonus hug from Arshad Khan. It's in seeing the end point of the film's journey, living, breathing and smiling that its effect is magnified tenfold, but the film is a resounding success regardless. Both its English and Urdu versions have the exact same edit – while the former has more jokes, the latter has more poetry – but in either case, the effect is a comforting hand on your shoulder, in the form of a film that lays out, end to end, the building blocks of surviving personal struggle and coming out the other end of it with one's kindness, and one's loved ones, still in tow.

Abu is playing in select theaters and various film festivals now.