The One Where We Revisit The Comforting Purgatory Of 'Friends'

(Welcome to Nostalgia Bomb, a series where we take a look back on beloved childhood favorites and discern whether or not they're actually any good. In this edition: grappling with Friends, the classic sitcom that is as comforting, and as frustrating, as home.)I do not know where Friends takes place.After living in New York for a little over a year (albeit in Brooklyn), and having spent several years prior visiting and familiarizing myself with the landscape, I have no idea where Friends, the culturally ubiquitous sitcom that aired for 10 years on NBC from 1994 to 2004, is set. Its frequent establishing shots suggest lower Manhattan, in the East and West Villages, but its actual references to New York landmarks are few and far between, and its attempt to create an artificial version of New York so blatantly casts aside any version of the city that it barely qualifies as an "idea of New York" the way that Woody Allen's Manhattan or How I Met Your Mother do.I've spent most of my life with Friends. Late nights sick or bored. Friends, with its unchanging landscape and immovable sense of time, its reliably growing or immaturing of its six leads, is insular, never engaging or touching a reality outside of itself, like the Bermuda Triangle of '90s sitcoms. And yet, for all of its lack of change, and its consistent hegemony and homogeneity, or because of it, it feels a bit like home.Admittedly, it's the kind of home you grow out of and seek to get away from, that's not necessarily good for you, but nonetheless shaped – for better and/or worse – your view of the world, and, god forbid, your speech patterns (Could I be anymore self-deprecating?). Rewatching Friends once every few years is like returning to Connecticut to remember that Connecticut is kind of trash and boring, and there's a select part of it that you like, but you mostly find it unbearably myopic and kind of bigoted, and not even in a way that you can excuse with, "It was the '90s" anymore.Ironically, I started rewatching the series again because I finally lived in the place where it ostensibly was set, but the world of Friends has never felt so devoid of an analogous real life location. It's the home, the family dinner, the small town you mostly don't like, but where you remember the route to get ice cream better than you know your mother's cell phone number (in my defense, she keeps changing it). You could fall asleep here, but you'd need to take the train home the next day before you get sucked in.

The One with the Ensemble and Question of “Progressiveness”

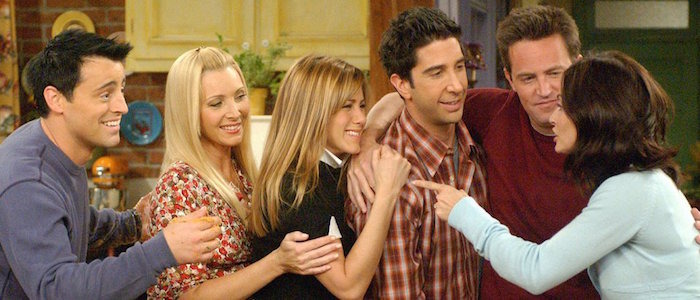

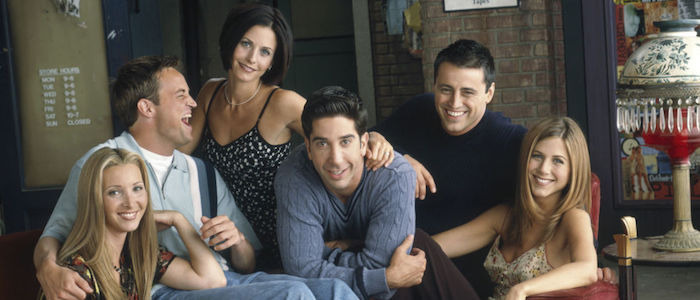

Little of Friends seems progressive, per se, and I don't think that was ever the intention. But even within the context of sitcom history, its formula was simple: juggle its six leads – Rachel, Monica, Phoebe, Joey, Chandler, and Ross – so that they are, in one way or another, adhering to some failure of communication. With each other, with lovers, with enemies, with co-workers or bosses or employees. No one is talking straight. Granted, the talking is pretty good; for its first four seasons, its colloquial approach to the close dynamics of its cast, and the impressive chemistry between them, lent the show an authenticity that was, and continues to be, its primary selling point: you want to spend time with these characters not because any of their follies are particularly interesting, or that they're particularly interesting people (save maybe Phoebe and Joey; what do these people even do again?), but because they seem to genuinely like being with one another.If the show were a bit more self-aware, it could have been bent as a caustic comedy about horrible people being horrible, but maybe we didn't need Noah Baumbach on NBC's primetime schedule. There is an ease and effervescence about the performances for the bulk of series, that the actors know their characters arguably better than the writers do, which is perhaps why it's been so easy to conflate the careers and lives of its stars with the people they played. Maybe you wouldn't really want to be friends with Chandler, but the idea of being friends with him was, at least, somewhat entertaining an intellectual game.Ironically, the authenticity imbued into these characters for 10 years was never given to people people, but, as maybe is the trend for the show, the idea of people. Everyone – Rachel's rich brat, Monica's shrill neurotic (I am aware of "shrill" being a loaded term), Phoebe's ditsy hippie, Chandler's misanthropic comedian (lord know what he actually does for a living – transponster?), Joey's lothario actor, Ross's pathetic paleontologist – is really an outline, and so much of the heavy work seemed to be left up to Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa Kudrow, Matthew Perry, Matt LeBlanc, and David Schwimmer to fill in the lines. They're just short of caricatures, but by design.

The One with Phoebe’s Class Discourse

In the time since the characters vacated their unrealistically rent controlled East Village two bedroom, Lisa Kudrow has rightfully be hailed as a comedic genius, with a talent on par (maybe more deserving) with the much ballyhooed and over awarded Julia Louis-Dreyfus. She's done Web Therapy and The Comeback, and she never feels like she's doing a different version of Phoebe; rather, Kudrow is just a flexible, talented comedic actor. Kudrow's Phoebe is kooky, Your One Weird Friend Who, and, more so than Joey, is a placeholder for any discussions (read: lowbrow jokes) it wants to have about class and poverty in New York. She's weird and we love that she is weird, because, in spite of the fact that Phoebe's head is constantly in the clouds, she is, along with Joey, one of the most grounded characters on the show.She's honest in a way that is coded as a way of survival; her past on the streets, living in destitution after her mother's suicide, is a cruel kind of texture that rarely feels satisfying as far as character backstory, but it does reveal why she's as close with the group as she is: friends like these (the show's original title) are not to be taken for granted. Her devotion, and her flightiness, in relationships feels a little more meaningful because we're told that she didn't have much before, which makes every decision a cost/benefit analysis.It's never explicitly detailed, not does it actually make much sense, but Phoebe's arc is a reversal of Rachel's. The impetus for the show laid out in the pilot was a loose riches to rags joke: spoiled Long Island girl leaves her fiance at the altar and tries to make it in New York, confronting the realities of what that implies by being cut off by her wealthier than thou family, working as a waitress, and hanging out with middle class people. That narrative is thrown out by season three and five, when Rachel gets a job at Bloomingdales and Ralph Lauren, respectively, and while it's admirable to watch someone who has, so we've been told, been so dependent on others become self-sufficient, little of it lands on its own terms.Conversely, Phoebe slowly, but surely (and with no explanation!), becomes more and more affluent, if only evidenced by her clothing and her spending habits. She has the least steady job out of the entire cast, freelancing as a masseuse, and yet ascends to a financial stability where she can live alone by late season seven (she had previously lived with someone named Denise). And although she's alienated by her soon-to-be husband Mike's (Paul Rudd) extremely wealthy family in season nine (he roughs it as a piano bar guy), the implication is that she's become at least as middle class as the rest of the group.

The One Where I Got Too Stoned and Sung the Praises of Jennifer Aniston

That Rachel's short riches to rags to sense of self-empowerment doesn't land on its own terms does not mean that it doesn't land; on the contrary, it lands specifically because of Aniston's performance. The level of Aniston's fame as both sitcom actress and movie star always got in the way of fair evaluations of her talent, in my opinion, and although I always liked her on the show, it only occurred to me recently, while incapacitated on a weed cookie, that Aniston was one of the great comedic actresses of our time, less obvious about her talents than, say, Kudrow. Especially evident in seasons two to four, Aniston acutely can lean into Rachel's brattier tendencies for maximum comedic effect without ever losing the character's humanity.Actually, what is most important, and most impressive, about Aniston's performance is that Rachel has any humanity at all. Each character gets moments here and there throughout the series that are supposed to solidify them as Real People with Real Emotions, but they come a few times a season, if that; it's rarely their job to convey a kind of nuanced complexity, which is indicative somewhat of the show's format. But Rachel always felt relatively human from her first appearance on screen: bursting in through the door of Central Perk, disheveled with her wedding veil all akimbo, her reactions as she's introduced to the main group are that of someone who has a dozen things racing in her mind, but is so precisely bred to pay attention to whatever is going on in front of her to keep up appearances. Ross and Rachel's arc is only sustainable for how much Aniston gave weight to her performance; it's best when she quivered, teetering between sadness and fury, like when she told Ross that the two will never happen after he made a list of her flaws, that he must "accept that". She makes up for what we don't see of the character, what was missing from the writers: her business acumen, her work ethic (of which there are hints in season three and nine), etc. Aniston prizes Rachel's emotional intelligence and versatility.Aniston's filmography is impressive, from Mike White's The Good Girl to the performance that got her this close to an Oscar nomination in Cake, she's as good at the complexity of a unidimensional character as she is playing to the audience for the broader bits of comedy, shifting easily between crying for laughs and weeping to yank on your tear ducts. I'm too removed from the series' run to know if this was an accurate statement at the time, but Aniston is often the unsung hero of Friends, its most real element.

The One With the Problematic Elements

Having something "real" on a show like this is significant when the majority of it takes place in a bizarre vacuum of nostalgia. It's a show where it can tout its second season lesbian wedding as liberal and progressive, but then pad out the rest of the series with gay panic. And while it's not entirely useful to wag your finger at a two decade old series for making bigoted jokes, it's mostly disappointing that they're very often lazy. Male insecurity is often the root for its jokes of the homophobic and misogynistic brand, an unending volley between the men who are scared that something makes them, or a friend, or a family member queer or emasculatatory, and the women who need to echo again and again, for 10 years nonstop, that they're being morons.For the first four seasons, even though this is when the show is at its best, it's not uncommon for the show to reduce itself as a myopic "battle of the seces" scenario where men are trying to fit everyone in a box – mostly Ross and Chandler – and women are telling them to stop that and let people be. Ross's son, Ross's ex wife, Chandler's parents, etc., etc. When Phoebe introduces a New Age-y book that posits women as wind keepers in season two, it's a thinly veiled metaphor for the women's sense of agency and feminism, but the episode distills the entire series' bizarre gender dynamics, a ceaseless battle for control and autonomy, even within the show's limited scope in terms of race and class.Is this a "real" element not unlike Aniston's agile performance as Rachel? A lot of white straight cis men are insecure about themselves, put off by otherness, etc. But the queerness of the comedy of queerphobia is too commonplace and generic throughout the history of comedy – written, verbal, physical – for it to resonate as sincere or edgy or even lightly satirical. The exception to this might be Joey; Matt LeBlanc is so good at playing an actor that's so bad. But Joey, also frequently dirt poor, was also written with enough wiggle room in how he feels about his masculinity that he occasionally sidesteps some of the easier, dumber restrictive gender stuff. He's childlike in many ways, both naive in how others' might perceive him, in a way that Chandler and Ross are hyper aware of that, and yet fairly confident that he often ultimately does not care. He knows what he's good at, sort of; at least when it comes to some basic ideas about how he understands his relationship to his own body and others'.Ross, Chandler, and Monica, at this point in the essay, come out as the problem characters, the first two so bizarrely toxic that they literally could not pass in a reboot and the latter so unfairly written in the later seasons that she, too, would risk being the subject of a thousand think pieces.Some of the effects to these characters can be somewhat contextualized with, using air quotes, the attitudes of the time, but the evolution of how we discuss power in interpersonal relationships, through racialized and gendered lenses leaves little argument for these characters to exist. Ross's pedantry may have been a blueprint for The Big Bang Theory, but he's too jealous to not be an unreal caricature; Chandler suffers from delusions of comedic grandeur, so convinced that he's funny and so unable to recognize the limits of his jokes; and Monica made such dramatic changes in character over the course of the series, becoming shouty late in season four, and mean midway through season seven, that she feels like disparate parts of a neurotic archetype. None of these characters make sense anymore, not in a contemporary comedic landscape, at least.

The One With All the Insularity

There are parts of Friends which are happily a sham, basking in its fakery because it never intended to be real, even on multicam sitcom terms. The parks – I have no idea where they're supposed to be playing football in the season three Thanksgiving episode...Tompkins Square Park? – are grey and miserable and, in their attempt to resemble the spirits of New Yorkers, almost get away with an honorable artistic/spiritual verisimilitude. Even its iconic Rembrandts sung theme song, which you can hear on repeat in Hell (and I like it!), seems at an ironic distance from what actually happens on the show, though a good representation of its aggressive nonspecificity. (These people are, like, almost never at their jobs.)That generalness is basically evident in the title of all of its episodes, beginning with some version of "The One with/Where/etc", as if trying to recall some vague inkling of a scenario without any tactile detail. The headline of a Vulture piece from 2016 asked "Why [do] so many 20-somethings want to stream a 20-year-old sitcom about a bunch of 20-somethings sitting around in a coffee shop[?]" and most of the answers suggest that it's the insular, unrealistic world that's comforting. It's a show you can fall asleep to, and those interviewed in the article echo a melange of permutations of the answer, "These people do not have real problems; these are not real people problems".But it might be a little more than that. Friends stands somewhat as an anomaly because of how nonspecific its world can be and now much it doesn't even want to engage with its own world, nevermind the one outside it. Its legacy stands in antithesis to stuff like Norman Lear's work, such as All in the Family and One Day at a Time (both its original and its aggressively woke reboot), and even The Golden Girls and Designing Women, sitcoms that expressly wanted to address social context and the politics that made its content and audience. But Friends even stands at odds with the ostensibly anodyne Frasier or Seinfeld, two of its NBC competitors, that either could get away with a little myopia because of how it dealt with class and cultural divides or was entirely predicated on its characters' sense of insularity.Most of my childhood was spent quasi-rebeliously watching Friends with my dad, at least from age seven. We had all the seasons on DVD, back when they had spliced in some of the extra jokes that had been cut for time. The original television cuts are the ones on Netflix – the missing gags stand out to me like an absent garnish on a mediocre side dish at Burger King. I identified as a Ross in high school and then realized how self-pitying that was of me. (Reader: I am still a Ross, who pretends to be a Chander, who wishes he were a Phoebe.) Like the numerous 20-somethings in the Vulture piece, I have spent many nights falling asleep to the familiar sounds of its canned laughter. I'm nearly the same age as some of the characters when the series began. My vocal affectations have traces of mostly Chandler and Monica (so a friend told me). I'm embarrassed by the show, but not by how much I love it. It is truly special in how disengaged it is. It's the brand of frozen lasagna I would eat while watching that hasn't updated its logo in a decade.Delicious garbage.

The One with the Meaning of Home

What is often said about the show now is how poorly it has aged. It's aged like the odor of cheese. And yet, paradoxically, it's addictively rewatchable, at least for those of us with little dignity on the line. Friends ultimately did not have much to say about its own time and its own legacy because that would suggest it wanted to at all. Friends floats in space, able to be picked up at any time and discarded, tasting the same all the way through, never entirely deepening. It's the Ruby Tuesday's of sitcoms.While someone on Twitter floated around the question of who of the cast would have voted for Trump, the question doesn't actually make sense because of how staunchly apolitical the show was. Yeah, yeah, they're liberals, because they're New Yorkers, but unlike Will & Grace or Roseanne, they made a concerted effort not to talk about capital P politics in any form. Absolutely, yes, apoliticality is a form of politics. So what would be the point in rebooting the series if nothing will have changed?In the end, its homogenous, LA-set-lazily-posing-as-New-York suggests that Friends is like a bland Utopia of kind of bourgeois (mostly) straight white folks where its politics is nothingness. It may not be very New York, but its disregard for anything outside of itself is a certain brand of Americana. Its brand was eschewing politics with stakes, beyond generic issues of sex and imitated fraternal/sororal love, like a group of people just trying to get through dinner without a fight. An idea of togetherness. No one has to learn here, nothing meaningful at least. (Makes for good depressive period watching.) An excuse to not do anything you're supposed to do. (Maybe Frances Halladay is a fan?)Utopia, or maybe Purgatory, if you think about it. Just like home.