How Rodgers And Hammerstein Shaped The Hollywood Musical (And Almost Killed It In The Process)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Over the course of their careers, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein wrote hundreds of songs. They created Oklahoma!, Carousel, The King and I, South Pacific, and The Sound of Music — and in the process, they revolutionized musicals as we knew them.In the new book Something Wonderful, Todd S. Purdum examines the pair's prolific work on the stage, following them from their separate early careers through their partnership and death. But he also looks behind the scenes at the movie adaptations of their work, which employed daring new technology and shattered box office records. They also, arguably, contributed to the demise of the film musical in the 1960s. And it all began with a less than auspicious introduction to Hollywood.

First Films

By Purdum's account, Rodgers and Hammerstein's first forays into the movie business left them hating Hollywood. Hammerstein briefly moved to California in 1929, signing a contract with Warner Brothers to write four musicals over two years. But his first film, Viennese Nights, was a dud. Although Hammerstein completed his second musical, Children of Dreams, Jack Warner quickly bought out his contract before the writer made the final two films. Hammerstein went home to New York.Rodgers had a similarly bad time. Like Hammerstein, he headed west to chase the success of The Jazz Singer, which had led to a huge demand for movie musicals. Rodgers arrived in 1930 and also signed a contract with Warner Brothers. But he hated his first movie, The Hot Heiress, and apparently the moviegoing public did, too. After it bombed at the box office, Jack Warner bought out the rest of Rodgers' contract, but the composer didn't head home just yet. He ended up working on a much more successful Paramount musical, Love Me Tonight, with director Robert Mamoulian, who would become a frequent fixture in Rodgers and Hammerstein productions. But the movie work that followed was hardly as satisfying, and by 1935, Rodgers was also back in New York.After working with different partners, the pair officially joined forces in 1943 with their stage hit Oklahoma! It was considered a Broadway revolution at the time, since it was the rare musical that fully integrated the songs and dance into the story, making the numbers pieces of plot development rather than disconnected spectacle. Oklahoma! was an instant hit, and its success led to an avalanche of offers. Despite their aversion to California, Rodgers and Hammerstein took a job offer on State Fair, the musical remake of a 1933 Fox family comedy. They'd contribute original music under one stipulation: they had to write it in New York. The studio agreed. Rodgers and Hammerstein picked up an Oscar for Best Original Song in the process, but they quickly resumed work on new shows and closed the book yet again on Hollywood. They wouldn't work on another movie for nearly a decade.

Box Office Bonanza

The duo could only avoid Hollywood for so long, and by the mid-1950s, Rodgers and Hammerstein decided to give movies another go. They started with their career-defining smash hit, Oklahoma!, which was the first movie to use a new wide-screen process called Todd-AO. Producer Michael Todd developed the format to improve upon Cinerama; Todd-AO films were shot in 65mm and projected on a wide, curved screen to give the footage a panoramic feel. It was perfect for the sprawling landscapes of Oklahoma!, and Rodgers and Hammerstein would use the process for South Pacific and The Sound of Music as well.Other experiments were less successful. For South Pacific, director Joshua Logan decided to use tinted filters to echo the song lyrics about "bright canary yellow" skies and give certain shots a blurry border. Initially, he shot everything with and without the filters, but this process soon proved too arduous. He opted to shoot just with the filters, reasoning he could remove any colors he didn't like in post-production. But those filters tinted the negatives, making any later corrections exceedingly difficult. Critics savaged the choice, dinging Logan for "smear[ing] 'mood' all over the big scenes."But despite some missteps, Rodgers and Hammerstein movies proved to be instantly, massively popular. According to Purdum, Oklahoma! brought in $9.5 million, ranking as the fourth-highest grossing film of 1955. The King and I and South Pacific amassed even larger profits, before The Sound of Music shattered records everywhere. The movie made $158 million worldwide, or about $1.2 billion when adjusted for inflation. It still ranks as the third highest grossing movie of all time on the adjusted box office charts, right after Gone With the Wind and Star Wars. And people weren't just seeing the movie — they were memorizing the music. The Sound of Music soundtrack would stay at the top of the Billboard charts for a whopping 14 weeks, longer than albums from Elvis Presley or The Beatles.These films, like the original musicals, were bursting with postwar optimism and sentimentality. Although they frequently delved into dark subject matter, they promoted a sunny worldview which was essential to the duo's work. Theses stories were also steeped in Rodgers and Hammerstein's own social values, values that included tolerance and inclusion. These were themes that permeated much of their work, not just South Pacific with its, at the time, controversial screed against racial prejudice, "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught." It's also evident in their lesser known movie adaptation, Flower Drum Song, would prove to be a rarity for 1961 with its almost entirely Asian-American cast.

Casting Calls

Just as Rodgers and Hammerstein attracted the best of Broadway, Hollywood royalty came out for their movies. One of the more famous, outrageous casting tales concerns Frank Sinatra, who nearly played the male lead in the film version of Carousel. The crooner agreed to the part and made it all the way to the set before things went awry. After the director, Henry King, explained to Sinatra that he'd be shooting everything in two different formats — so, twice — Sinatra changed his mind. "I signed to do one movie, not two," he said, before getting in his limo and heading home.But the stories go back to Rodgers and Hammerstein's first major adaptation: Oklahoma! The way Purdum tells it, just about everyone in town was up for a role. Josh Logan, a frequent Rodgers and Hammerstein collaborator, apparently suggested a young, not yet famous Paul Newman for the lead role of Curly. But director Fred Zinnemann thought the kid was going nowhere. "Paul Newman is a handsome boy but quite stiff, to my disappointment," he wrote. "He lacks experience and would need a great deal of work. Still, in the long run he may be the right boy for us. He certainly has a most winning personality although I wish he had a little more cockiness and bravado."Zinnemann also considered James Dean for Curly, and was kinder on his screen test. Zinnemann called him "an extraordinarily brilliant talent," but thought he lacked "the necessary romantic quality." Other names in contention for leads included Montgomery Clift, Van Johnson, Lee Marvin, Debbie Reynolds, Rosemary Clooney, Doris Day, and Janet Leigh. The movie ultimately settled on the Broadway talents Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones for the lead roles.The story of how Shirley Jones entered the picture is one of the more uncomfortable anecdotes in Something Wonderful. After dazzling Rodgers and Hammerstein at one of their open auditions at St. James Theatre, Jones landed a chorus role in the stage production of South Pacific. But the duo had bigger plans for her. At the age of 19, she clinched the starring role of Laurey in the film adaptation of Oklahoma!. Rodgers summoned her to his office, where he closed and locked the door. He made a "cold-blooded pass" at her, which Jones apparently brushed off by saying she had a boyfriend and, when that didn't work, making a joke about Rodgers being her grandfather. "It is a tribute to Richard Rodgers's professionalism that he didn't take steps to fire me or ensure that Oklahoma! was the last movie I would ever make," she later recalled.That's a pretty horrifying statement, one that's completely glossed over in the book, along with the entire story. Jones has talked about the incident before, and journalists have always treated it with a gross levity — in 2013, NPR's Peter Sagal broached the subject by saying he "love[d] the fact... that Richard Rodgers became first in a long line of show businessman to hit on you."So-called casting couch tales of young ingenues entering locked offices with much older, powerful men who can make or break their careers have often been framed this way — as silly, maybe even salacious tidbits of movie trivia and nothing more. But in a post-Weinstein era, it's wantonly irresponsible to keep perpetuating these ideas. We need to keep having these difficult conversations, and although Purdum acknowledges the story is "dark," he does not truly grapple with Rodgers's lecherous qualities. He glancingly references Rodgers's famous "womanizing" (itself a loaded word) without ever seriously interrogating it, leaving readers with many questions and an uneasy feeling about the book's subject.

Putting It on the Road

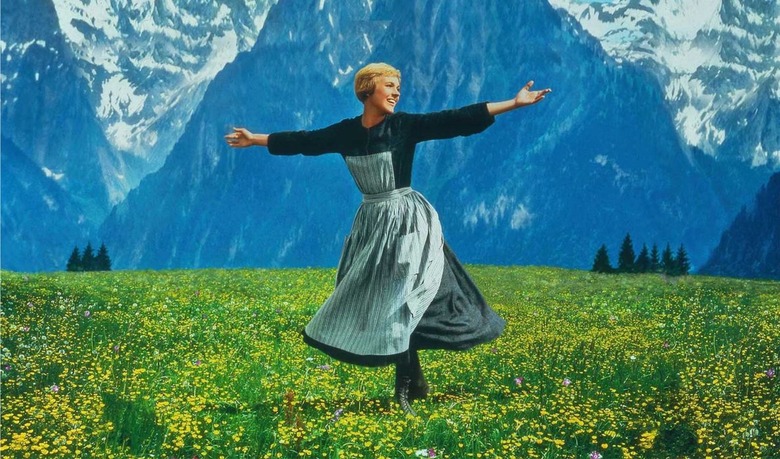

For all their innovation, Rodgers and Hammerstein also played a hand in "killing" the movie musical, at least by some historians' accounts. As Matthew Kennedy argues in Road Show! The Fall of Film Musicals in the 1960s, studio executives saw The Sound of Music as an opportunity to expand the movie musical genre. But they went about it all wrong, interpreting the secret to that movie's success as excess. It was the grand European setting, the epic story, the roadshow release (including an intermission!) that won over audiences, they reasoned.So they rushed a bunch of bloated or just plain bad musical extravaganza into production. Doctor Doolittle is one notorious example, a soulless moneypit that embarrassed just about everyone involved. Julie Andrews, high in demand after her star turn as Maria, also headlined two ill-advised musicals: Darling Lili and Star! The latter was such a disappointment that Fox rereleased a shorter version and even changed the name, trying desperately to recoup their losses. Nothing worked. And after bleeding so much money on bad movies, studios concluded that audiences simply didn't like the genre and dramatically slowed production on new musicals. The days of consecutive Rodgers and Hammerstein hit movies, or consecutive hit movie musicals in general, were over. And they never really returned.

Making Something Wonderful

Purdum's book offers insight into the minds of two incredibly famous music men. There's a wealth of information on their creative process, from scrapped lyrics to letters of frustration dashed off to friends. If their outrageous success on Broadway was remarkable, their bumpy path to Hollywood was possibly even more interesting. Despite their lifelong aversion to L.A., the pair impacted the movie musical dramatically, leaving behind a legacy of hit films that moguls are still trying to replicate. Hopefully, they take away the right lessons this time.