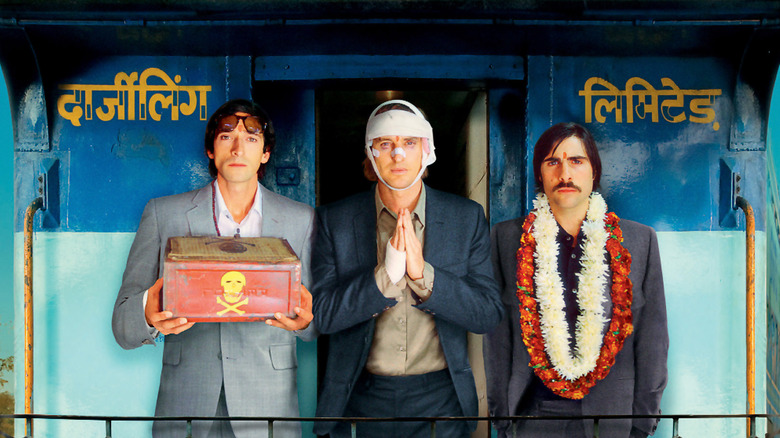

The Unpopular Opinion: 'The Darjeeling Limited' Is Wes Anderson's Best Film

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: Wes Anderson's The Darjeeling Limited isn't just underrated, it's the best film he has made yet.)Wes Anderson is more than a director – he's a brand. Beyond enjoying name recognition, Anderson has an identifiable aesthetic rivaled perhaps only by Quentin Tarantino among indie filmmakers. A cottage industry of trailer remakes, Etsy shops and Instagram accounts has sprung up around his name. His films' releases are the closest things to events outside of major studio tentpoles.

So how did the 10th anniversary of The Darjeeling Limited pass by last October with hardly any significant decade retrospective piece? Anderson, ever a reliable click-generator for film sites, should easily have inspired some online chatter encouraging reevaluation for better or for worse. Instead, Anderson's 2007 film simply cemented its status as his most forgotten film. While not the worst (an honor sometimes reserved for The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou since most people cut his debut Bottle Rocket some slack), few rank it among his iconic classics like Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums or Moonrise Kingdom.

Consider this a belated invitation to reconsider the movie. I maintain The Darjeeling Limited is Wes Anderson's best film, a perfect blend of style, story and sentiment. You can't quote it as easily as Rushmore, but Anderson's deadpan dialogue retains its snapiness. You can't dress up as it characters for Halloween as easily as The Royal Tenenbaums, but the personalities are as vibrantly acidic as ever. You don't have an ensemble of stars to fill the poster like The Grand Budapest Hotel, but Anderson goes deeper than ever on three brothers who are among his most completely realized cinematic creations.

Anderson Understands Brothers

There are very few screenwriters who can write effective dialogue for men, in part because they tend to use a lot less of it. There's a particular economy in male-to-male communication, one that speaks loudest in attitudinal maneuvers, passive-aggressive gestures and mutually understood restraint. This goes doubly so for male relatives, especially brothers.

I can't think of a film that pinpoints the way brothers operate in a space together quite as accurately as The Darjeeling Limited. So many brisk conversations and petty arguments transported me to similar situations with my own younger brother (and even male cousins closer in age to me). No matter your actual age, the thickness of blood ties tends to bring out the children inside of guys. The socially conditioned drive for competitiveness means you're always jockeying with each other to occupy the pole position in the eyes of your parents.

Before Adrien Brody's Peter muses that he was the favorite child of his deceased father to significant uproar, the estranged Whitman brothers quarrel constantly over their relative status. Owen Wilson's Francis frequently scolds Peter for hoarding so much of their dad's former possessions, from his giant prescription sunglasses to his razor. "I don't want you to get the feeling that you're better friends with him than we are," Francis eventually declares. It's a brutally honest statement that lays bare the jealousy undergirding so many sibling relationships. We pay lip service the notion that all children are equal in the eyes of their parents, but a society that teaches us that there are winners and losers in virtually every field of life conditions us to question this supposed tie.

Sibling rivalry generates a strange economy, too. The Whitmans jostle for favorite status with each other by disclosing things to one brother while the other is away. The secrets are not merely about the information – they're about trading status. These moments never feel malicious because they're the recourse of men who otherwise struggle to express the things gnawing away at their insides. Brotherly love lacks a concrete spoken language, so it often spills out through less glamorous channels like physicality and displays of brute force.

Peter's comment about being the favorite son eventually spills over into an all-out brawl with Francis, requiring mediation in the form of pepper spray by their third brother, Jason Schwartzman's Jack. Just before deploying the deterrent, Peter and Francis have taken their fight to the floor – but are also saying that they love each other. Jack remarks, "I love you too but I'm gonna mace you in the face!" It's a moment of pure family dysfunction that never loses sight of what causes these fraternal skirmishes in the first place.

Anderson Shows His Most Nakedly Emotional Characters

If you poked the characters in The Royal Tenenbaums or The Grand Budapest Hotel, you'd hit nothing but air. They're hollow by design, a trend that has grown particularly more pronounced in Wes Anderson's work over time. The characters often draw comparisons to puppets or paper dolls, a nod to their artificiality that borders on surrealism. The environments in which they move around, impeccably crafted geometric sets with clean décor, enhance the sense that these are not actually people.

If you poked the Whitman brothers in The Darjeeling Limited, however, you could draw blood. They are the closest thing Wes Anderson has come to putting fully-fleshed humans on screen, and it certainly helps that they move through locations in India that feel and look entirely real. The Whitmans maintain the acerbic wit of Anderson's most indelible creations, but they react to their surroundings authentically as opposed to the comedic over- or under-reactions that traditionally define his movies.

Wes Anderson's films have never shied away from dark subject matter – family estrangement, midlife crises, the triumph of fascism over civilization – but he often treats them with a thin veil of irony. The obvious construction of characters, never pretending to masquerade as real people, has a distancing effect that allows viewers to observe their pains from an elevated position outside the narrative. And yet, Anderson has always complimented this stylistic proclivity with a contrasting sensibility of real sincerity for his characters.

The Darjeeling Limited is arguably Anderson's least irony-steeped production. Its relatively narrow scope allows him to plumb the depths of his characters' pain more deeply than ever. On their locomotive journey through India, the Whitman boys have many opportunities to face their respective traumas head-on.

Francis, the planner and machinist behind the "spiritual" journey to bring the brothers closers together again, receives a constant reminder of his fragility from the large bandages draped around his head following a motorcycle accident. He thinks he can magically repair every blemish in his life in the same way the bandages can reset his face back to normal. Francis plans an elaborate itinerary for he and his brothers to reunite with their long-lost mother, assuming that the endpoint will provide cathartic release for them all. But, to quote a popular cliché, healing is not a destination, it's a journey. He comes to this realization by the end of the film as he unfurls his bandages in the mirror while his brothers look on, admitting, "I guess I've still got a lot of healing to do."

Peter comes for the trip despite having a seven-and-a-half months pregnant wife waiting back at home. He's terrified of the commitment and responsibility that comes with paternity. Peter remains in such denial about the impending birth that he neglects to share the news immediately – and even then, he only does so when Francis isn't there. His fixation with holding onto items from his father suggests Peter still sees himself as someone else's child too much to fathom having a child of his own. At a key juncture on their voyage, the Whitmans must jump in a river to save three Indian children who fell in attempting to cross. They each try to grab one, but Peter is ultimately unable to secure his before hitting the rapids. "I didn't save mine," he admits in defeat as he carries the limp body out of the water. The incident reinforces Peter's deep fear that he will be unable to protect his own child.

Jack jades himself from feeling the pain of his father's death and his breakup by spinning reality into fictions. He's shockingly eager to share his writing with his brothers; Peter instantly recognizes himself in the recounting of the trip to their father's funeral. Jack claims it's fiction, fooling no one. Throughout the film, he's unable to sort through his emotions logically as events happen, contradictorily phoning his ex-girlfriend's answering machine while courting a stewardess on the train. By the end of the film, he's still using the written word as an emotional release valve. But when Peter opines, "I like how mean you are," Jack decides not to contradict the assertion and admit he is, in fact, writing about himself.

Each brother reaches a very different stage of acceptance and enlightenment, but the plot of The Darjeeling Limited sets them all down the same path again. Anderson invites the audience not merely to watch the Whitmans' journey but take it with them. As The Kinks sing in "Strangers," played over the Whitman brothers walking to the funeral of the Indian child, "Strangers on this road we are on / but we are not two, we are one." It's the closest thing Wes Anderson has done to a project inviting identification, rather than just observation.

Anderson Connects Style to Story

Think of a quintessential Wes Anderson shot. It probably involves some kind of long tracking shot on a dolly through a symmetrical set. These shots showcase Anderson's visual bravura and are far more fun to watch than a chopped-up journey from Point A to Point B. In a larger sense, they track continuity through a space.

The Darjeeling Limited features Wes Anderson's best tracking shot, in part because it serves as the emotional peak of the film and connects to its larger themes. It occurs when the Whitman brothers show up unannounced at the Indian convent where their mother Patricia (Angelica Huston) now works as a nun. After their initial attempts at reconciliation fail, she proposes something a little more unconventional. "Maybe we could express ourselves more fully if we say it without words," Patricia suggests.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bDNINiiQxc

The four of them sit in a circle on the floor, communicating without talking. The camera starts in a close-up on Patricia, then pans around the room to catch each of her sons in varying states of contemplation over everything that led them to this moment. The camera then swings back to Patricia, who has let a bit of a grin slip onto her face.

Anderson then cuts to the children in the care of the convent and begins another pan. This one, however, defies spatial logic. As the camera moves to the right, it jumps from the convent back to the train, showing the stewardess in her living quarters. Then it moves to a steward who butted heads with the Whitmans on the train. Then the shot breaks free of actually depicting people on a train altogether but still tracks as if the camera is moving car to car. We see the two surviving Indian children in the village, Peter's pregnant wife, an old man from the train, Francis' beleaguered assistant, Jack's ex-girlfriend, a businessman who Peter cuts off in the film's opening scene – and finally, a tiger that Patricia mentioned is terrorizing the neighborhood.

Beyond the crew members of the Darjeeling Limited (the train that supplies the film with its title), none of these people are literally on a train. Yet, by the motion out the windows in each locale, it's made to look like wherever they are chugs forward like a locomotive. Anderson is literalizing the train metaphor in this tracking shot, and in doing so, he connects all the characters in the Whitmans' orbit to their journey. All these people are on their own train ride trying to figure out their direction in life. The continuity is not merely special in this tracking shot – it's spiritual. And the final piece of the shot, the tiger, represents the grim fate that awaits us all.

We are all on a train moving through life towards our eventual death, suggests Wes Anderson in The Darjeeling Limited. In the meantime, why not try to understand the feelings and needs of our fellow passengers? With both his words on the page and images on the screen, Anderson leaves us better equipped to empathize and relate with those around us.