Pimpin' In Space: The Blaxploitation Roots Of Lando Calrissian

Solo: A Star Wars Story hits theaters this May, and the character everyone is the most excited to see isn't Han Solo. It's Lando Calrissian.

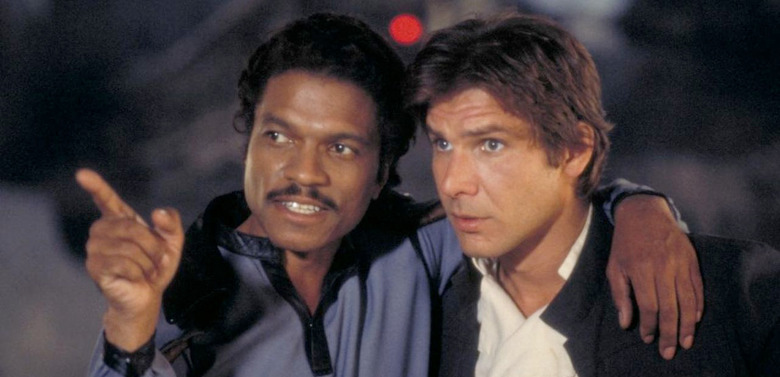

Lando, initially played by Billy Dee Williams and now Donald Glover, has been a huge force (no pun intended) in the Star Wars universe. His personality, good looks, and roguish charm have secured him the honor of being one of the most influential and coolest Star Wars characters of all time. But what many don't realize is how much Lando's character stems from another popular genre created before Star Wars hit theaters – blaxploitation.

Lando's characterization and his style owe a huge debt to blaxploitation. But Lando also adds another layer to the conversation blaxploitation engages in about black images in the media. How does Lando, colloquially called a "space pimp" by fans, contribute to the conversation and in what ways does he actually hinder how blackness is viewed in film? To mediate further on these questions, let's start with the beginning of blaxploitation itself.

Blaxploitation: the birth of the space pimp

George Lucas' films from the early 1970s, THX 1138 and American Graffiti, put him on the map as a filmmaking powerhouse. Interestingly enough, the early 1970s is when blaxploitation also became powerful in its own right, laying the foundations for Lucas' Cloud City swindler.

During the early '70s, film sales were waning dramatically. With more white audience members resorting to television and moving away from the cities (where the big theaters were) and into the suburbs, studios began catering towards black audiences, who were moving into the cities and had limited alternatives for entertainment. The genre that would become blaxploitation kicked off with Melvin Van Peebles' 1971 hit Sweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song. Being the first of its kind, the film was initially a long-shot for success.

"With no such thing as a marketing budget, Van Peebles released the film's Earth, Wind & Fire soundtrack before the film, and he would rely on the oral tradition, using strong word-of-mouth support, to help promote Sweetback to eager urban audiences," wrote The Root's Todd Boyd. "When the dust cleared, the film's success made Hollywood pay attention to the existence of an untapped audience. This set in motion a process that would give birth to a genre eventually referred to as 'blaxploitation' going forward."

The introduction of black men and women as leaders of their own stories cemented blaxploitation's popularity, despite the genre's harmful themes, such as physical and sexual abuse, hypersexuality, linking blackness and inner-city life to crime and drug use, and hypermasculinity. The genre, which created legendary films like Shaft, Coffy, Cleopatra Jones, and Superfly provided black actors and black audiences a way to create and consume stories starring black characters that would gain mainstream appeal. Several big names in entertainment participated in the genre's development, like Sidney Poitier, who starred in two sequels to In the Heat of the Night that would serve as a precursor to blaxploitation, They Call Me Mr. Tibbs! and The Organization.

By 1972, Bill Dee Williams was already a Hollywood star and the chief arbiter of cool; his roles in Brian's Song and Lady Sings the Blues cemented him as a huge talent and as a suave, debonair sex icon. But he also starred in blaxploitation films such like The Final Comedown, Hit! and The Take. Even in these films, Williams also played a compassionate hero looking for justice, further cementing his status as the new king of black Hollywood.

His brand of cool put him on Lucas' radar, who wrote "Actor – Billy Dee Williams – Cloud City leader" in his Empire Strikes Back story notes.

In the book, The Making of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, J.W. Rinzler wrote that Williams' sex appeal is what secured him the role of Lando. "His romantic onscreen image is what got Williams the part, according to [Empire Strikes Back director Irvin] Kershner, who says he 'really looks like a Mississippi riverboat hustler. Billy can do that charm fantastically."

Ironically, the description of a "Mississippi riverboat hustler" can read as racially-charged, despite Lucas' irritation at Star Wars being criticized as being racist due to its all-white cast. While Lando is supposed to be a character that acts independently from mainstream black caricature, Lando is still defined by his blackness.

"[Filmmaker, writer, and George Lucas biographer] Dale Pollock reports that Lucas was 'still smarting from criticism that Star Wars was racist,' so he 'conceived of Lando as a suave, dashing black man in his thirties,'" wrote Kevin J. Wetmore Jr., author of The Empire Triumphant: Race, Religion and Rebellion in the Star Wars Films. "The irony is that Billy Dee Williams was interested in the role precisely because the character wasn't specifically black – there is nothing inherent in the script that makes Lando a person of color, other than the fact that specified in the script is that half the residents of Bespin are black. Of course, in the final version, only two or three residents of Bespin are black."

Lando further defines the mainstream image of blackness as being one synonymous with coolness and slickness. But with that image comes negative associations of blackness; being shifty, dangerous, and untrustworthy. It's unclear if Lucas was directly inspired by blaxploitation, but blaxploitation's pervasiveness certainly informs Lando's character, from the cape to his roguish personality. There's a reason why many fans refer to Lando as a pimp in space.

Lando repeats blaxploitation’s mistakes

In just looks alone, Lando fits in with the Sweet Sweetbacks, Dolemites and SuperFlys who preceded him. The iconography of the pimp is one of the lasting, controversial effects of blaxploitation popularity. The image is emblazoned in our minds; a charismatic black man with permed-straight hair, a flashy hat, and equally flashy clothes. A fur or cape of some kind was always in the mix. Lando, too has relaxed hair (albeit with more body and curl than most blaxploitation pimps), a saunter, and an expensive-looking blue cape lined in luxurious gold fabric, complete with a gold neck chain.

The sartorial language of the blaxploitation pimp isn't all fluff; it actually has substance. In its own way, the pimp uses clothes as an f-you to The Man; he wants to show he has made it, regardless of his circumstances as a black man in America.

"Some end up celebrating the pimp because he's a version of the antihero born out of specific conditions," Glenda Carpio, professor of African and African-American Studies and English at Harvard, said to Dallas News' Chris Vognar. "Those conditions are relatable and familiar to the hip-hop community. It's related to the history of the trickster, so it's an updated version of an antihero that has been part of African-American culture for decades."

Author Ed Guerrero analyzes this further in his book Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film.

"...[T]he pimp-hustler hero and his urban milieu have enjoyed a long, colorful history in black literature, folklore, and oral tradition, where the sly victories of the gangster or trickster persona were one of the few ways that African Americans could turn the tables on an unjust racist society. Thus the cool, counterwhite, underworld perspective of the black gangster or outsider has enjoyed much attention in African American popular literature, most notably in the novels of Robert Beck (a.k.a. Ice Berg Slim), as well as the more polished literary works of Chester Himes and Donald Goines, all of whose novels inspired many film scripts."

Looking at Lando from a blaxploitation perspective, the character continues the tradition of updating the trickster persona via the pimp. Even though Lando is in a galaxy in which racism doesn't exist, his costuming – his cape in particular – calls back to the movie pimps of the recent past, showing the audience he has a mystique the other (white) characters can't quite replicate or understand. His clothes exemplify his ability to work outside of the system that is still, despite it being in a galaxy far far away, set and run by white people.

Lando's actions also firmly showcase the character's trickster origins; Before becoming the Baron Administrator of Cloud City, Lando was a "smuggler, gambler and card player" who only lost the Millennium Falcon to someone even trickier than him, Han Solo. At first glance of Leia, Lando tries to take Leia away from Han with his smooth-talking and ladykiller demeanor. And, even though he's Han best friend, he still double crosses him by giving him, Leia and Luke over to Darth Vader.

However, the one flaw in Lando's pimpish anti-heroism is that he doesn't come out on top. It is the sense of victory that allowed many to look over the blaxploitation pimp's damaging stereotypes to the black community. For instance, Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton wrote an essay declaring Sweet Sweetback, as written by Boyd, "a cultural reflection of the same types of political ideas that the Panthers championed," suggesting "that the movie was the 'first truly revolutionary black film."

But Lando loses, and his loss showcases how the street-justice style of the pimp is just another side of the dangerous black male stereotype, a stereotype that allows people to believe black people are inherently criminal and sexually violent. Such is the case for Sweet Sweetback. Despite the titular pimp becoming the hero of the film via killing a police officer who murdered a black militant and thus becoming, as Van Peebles described, radicalized, Sweet Sweetback still loses in the sense that it provides a so-called revolutionary look at black urban life within the same contexts defined by mainstream white media and thought.

Lerone Bennett, the executive editor of Ebony Magazine in the 1970s, wrote a lengthy article called "The Emancipation Orgasm: Sweetback in Wonderland," shredding the film to pieces for its reliance on racist black tropes:

"The reasons for the movie's appeal, apart from the sex and violence, are obvious. First of all, and most importantly of all, the movie shows a black man thumbing his nose at society and getting away with it. If Sweetback does not, as Mr. Van Peebles claims, win, he at least escapes, and black America, the author included, said: 'It's about time.' We've had too many movies of suffering blacks performing noble deeds and getting done in at the end. We've experienced enough defeats. What we need now is hope. Sweet Sweetback provides hope of a sort.

But, as Bennett continues:

"...Sweet Sweetback is neither revolutionary nor black. Instead of giving us new images of black rebels, it carries us back to antiquated white stereotypes, subtly and invidiously identified with black reality. Instead of carrying us forward to the new frontier of collective action, it drags us back to the pre-Watts days of isolated individual acts of resistance, conceived in confusion and executed in panic."

In this way as well, Lando's character harkens back to blaxploitation. His "individual acts of resistance," such as tricking Han and working with Darth Vader with the goal of securing Cloud City's protection, are "conceived in confusion and executed in panic"; he doesn't stop to think how his double-crossing could come back to cross him. All he knows are the ways of the swindler, despite his role as a government leader. His trickster ways are tied to his blackness, and whether or not Lucas realized this, he still gave his critics ammunition against him despite his inclusion of a black character.

Where does a space pimp go from here?

The question now is if Solo: A Star Wars Story will advance Lando's character in any real, meaningful way. So far, our most iconic image of young Lando features Glover wearing a pimpalicious fur coat. Once again, the iconography of the '70s blaxploitation era is employed, as well as its defining images of blackness in the media. At once, we're presented with a trickster hero for a new age, a new version of the Space Pimp, defining himself by his own rules while reinforcing the same box of limited thought about blackness that has hurt black characters before and after him.

Despite the double-edged sword he presents, black America has been happy to claim Lando as one of our heroes, just like many of us still claim the problematic portrayals of blackness in blaxploitation as points of pride. The reason we've accepted characters like these is because for so long, that's all we've been given. Even with everything I've written, I still think Lando's the epitome of the cool cat in space.

Since Solo was written before or during the time Black Panther was in the works, we can assume the film still works on antiquated, if subtle thoughts about blackness; if our first image of Lando is him in a pimp coat, what else can we assume? But in these post-Black Panther times, it'll be interesting to see how audiences, black audiences in particular, receive Lando. Will the character's trickster ways be overlooked, or will audiences rail against it, demanding from Lucasfilm a representation that views blackness in its entire complexity and not just its most marketable, reductive forms? Who's to say.

Regardless of what happens, though, Lando will always remain one of the coolest, most enigmatic characters of the Star Wars universe, and his addition to the conversation surrounding blackness in film will keep us talking for years to come.