Unlearn What You Have Learned: Luke Skywalker Is The Greatest 'Star Wars' Character

Years ago, when the American Film Institute released its list of the 100 greatest movie heroes and villains, three Star Wars characters made the cut: Darth Vader, Han Solo, and Obi-Wan Kenobi. There is no disputing Darth Vader. He's a pop culture icon. As a movie star, Harrison Ford is an icon, too – he also gave us Indiana Jones, the #2 hero on that list. And Sir Alec Guinness is just a legend, plain and simple.

So those are the winners of the high school popularity contest. Those are the Star Wars characters who show up in the senior superlatives section of the yearbook, boasting titles such as "Most Likely to Receive a Spin-Off." But while I love Darth Vader, Han Solo, and Obi-Wan Kenobi, and have been equally charmed by new characters like Rey and Finn, I would argue that there is an even greater Star Wars character, one who is — with the release of Star Wars: The Last Jedi — about to make his return on-screen as a speaking character for the first time in 34 years. That character is Luke Skywalker, the greatest hero that no one seems to give the time of day.

It seems strange that the hero of a trilogy should in some ways be relegated to the status of an unsung hero. Considering how well he is able to emote with a two-foot puppet as his only scene partner, Mark Hamill does not get enough credit as an actor. The conventional wisdom, based largely on A New Hope, is that his character is somehow less cool, even perhaps annoying at times. But if you trace his evolution through the original three Star Wars movies, his character undergoes the most interesting arc, maturing from a whiny teenager to the galaxy' s ultimate bad ass warrior.

As a dreamer staring off into the binary sunset, Luke Skywalker contains multitudes. He is the young George Lucas. He is a whole generation of kids. So break out your action figures, and let's talk about Luke. There are no The Last Jedi spoilers here.

How Luke Rises Above Wooden Whines to Instill A New Hope

With George Lucas handling the directing duties and also serving as sole screenwriter, the first Star Wars film, retroactively called A New Hope, had a purity of vision to it that none of its sequels can claim. This is not always a good thing. Lucas once proclaimed himself "the King of Wooden Dialogue." By his own admission, then, dialogue was never his strength.

Harrison Ford is well-known for saying, "You can type this shit, George, but you sure can't say it," and Mark Hamill is also said to have wrestled with his lines, complaining, "People don't talk like this!" To this day, Hamill still pokes fun at how Lucas's scripts posed an acting challenge with the way he autographs select Star Wars trading cards. With fewer New Hollywood peers in his orbit circa the late 1990s (no more Brian De Palma, for instance, to help critique and rewrite the opening crawl), Lucas's tin ear for dialogue would only become more pronounced in the prequel trilogy, as new actors were given the thankless task of performing leaden lines against blue-screen backgrounds.

Just to be clear, A New Hope is one of the greatest movies of all time. But if it could be said to have any major weakness, it is that some of its dialogue does not sound entirely convincing coming from its trio of young stars. Even Ford, who would go on to great things with Indiana Jones, Blade Runner, and The Fugitive, falls into a kind of cynical posturing with Han Solo at times. Older, more experienced actors like Sir Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing are able to elevate the material, bending the dialogue to their mouths, so that it sounds natural, even profound. But for their part, Hamill, Ford, and the late Carrie Fisher had something of an obstacle to overcome in terms of an intermittently clunky script that was nonetheless nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the 50th Academy Awards.

Whereas Obi-Wan Kenobi moves through the Death Star in a graceful fashion, a paragon of elegance in his robes, Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Princess Leia are caught up in a cheesier flick, running around on this space station, bickering and cracking wise. You can really see the combination of influences here: Obi-Wan is the samurai, a holdover from the influence of Japanese cinema on George Lucas, while the other characters are off on a different zigzag, one which betrays the story's Flash Gordon roots.

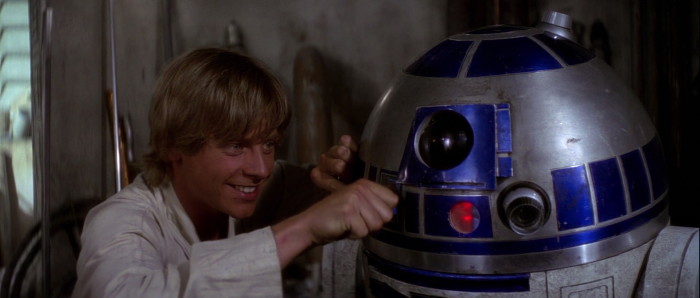

At this point in the Star Wars saga, Luke Skywalker is approximately 19 years old. When we first meet him, before the Death Star is a twinkle in any Millennium Falcon passenger's eye, Luke is stuck on a moisture farm in the middle of the desert. As his uncle assigns him Droid-related chores, his voice strikes a petulant note, offering up the infamous line of protest: "But I was going into Tosche Station to pick up some power converters!"

YouTubers have compiled supercuts demonstrating how "all Luke does is bitch and moan." In a weird way, the 19-year-old Luke almost reminds me of Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights. If you compare their voices, they are on a similar wavelength of whines. Both are caricatures of a kind. But the whininess arguably suits Luke's character as an immature teen, one whose go-nowhere farm life seems to be epitomized by the gripe, "It just isn't fair!"

This bratty quality seems to be hardwired into the Skywalker DNA, with Hayden Christensen's Anakin Skywalker taking it to the extreme. ("It's unfair! How can you be on the Council and not be a master?") Adam Driver's Kylo Ren shares the same family trait in The Force Awakens, but by then it has become a punchline, with the character throwing temper tantrums to comedic effect, sending Stormtroopers turning on their heels as he regularly destroys First Order property with his lightsaber.

Compared to his father and nephew, Luke Skywalker bears a much nobler spirit. There are moments, even within the same scene sometimes, when Luke goes from sounding annoying and whiny to sounding all too believable and human. Trapped in boring circumstances on his home planet of Tatooine, he tells C-3PO, "If there's a bright center to the universe, you're on the planet that it's farthest from." In that moment, you really feel for him. Then he attempts to use the droids as a bargaining chip with his uncle, and you can see that he just wants to get off this farm, and go somewhere and do something with his life. Rather like the young George Lucas, longing to be a race-car driver in his hometown of Modesto, California.

That is what makes Luke's arc the most compelling, even in the initial stages. Because soon he gets the call to adventure with Obi-Wan, and this sends him off on a series of daring exploits whereby he finds himself swinging across chasms, saving a princess, and being the pilot who fires the shot that destroys the Death Star. For the inner child, it is exhilarating to project oneself onto Luke.

Luke Skywalker vs. Han Solo: Who Wins the Fight? (Answer: Luke)

Again, I love Han Solo, but for the sake of argument, I think it's also worth pointing out how Luke and Han are on alternate trajectories in the original Star Wars trilogy. At the beginning, Han is the cool kid, whereas Luke is every other kid who ever dreamed of adventure. Even in A New Hope, when his character sometimes grates on the nerves, Luke still serves as a refreshing contrast to Han, his wide-eyed optimism cutting through Han's jaded, self-serving bull, like when he balks at the price Han demands for smuggling rebels, or when he chastises Han right as Han is about to take the money and run, abandoning the rebels in their hour of need.

It is interesting to note how Han's character, the skeptical space pirate, verbally reduces the other characters in A New Hope to archetypal forms, more than once referring to Luke and Obi-Wan as "kid" and "old man," as if to drive home the point of what this movie is – a fairy tale populated by stock characters. Perhaps that is why so many people latch onto Han as the coolest character, because he functions as another kind of surrogate for the audience, deconstructing and disbelieving, until finally, he becomes a believer, too.

By the end of the trilogy, Han has lost his edge. The Solo who goes into that carbon-freezing chamber in The Empire Strikes Back is not the same one who comes out in Return of the Jedi. You could argue that his romance with Leia and the experience of being frozen in carbonite mellowed him out, but whatever the case, Han's seen-it-all attitude gives way to a slightly neutered, dopier version of the character, prone to long, adoring looks at Lando Calrissian. When not functioning as a source of comic relief, Han remains clueless about the true nature of Luke and Leia's relationship. He also shows an ignorance of Luke's abilities, dismissing the intimations of Luke's Force sense as him being "jittery."

Luke, on the other hand, has come into his own as an almost fully formed Jedi. In The Empire Strikes Back, we still see glimpses of his old restless self, the impatient farmboy. On a swamp planet, he enters the mud hovel of a wizened green gnome. It turns out this gnome (for all intents and purposes, a Muppet, brought to life by Frank Oz, the voice of Miss Piggy and numerous others) is oh-so-much more than he seems. Revealed as Yoda, the legendary Jedi master, he calls Luke out on his failings, telling him that "all his life has he looked away to the future, to the horizon, never his mind on where he was, what he was doing."

Training with Yoda is the first step toward Luke becoming a mature figure. The second comes after his impetuous decision to race to Cloud City leads him into a trap, where he ends up squaring off against Darth Vader. The movie reaches the height of all despair with the revelation that Vader is Luke's father, at which point a despondent Luke literally flings himself into the abyss of the city's central air shaft.

The Luke that we see in Return of the Jedi has grown more hardened and zen-like from the trauma of this experience. Confident in his abilities, dressed in all-black and sporting a cybernetic hand, he's like some space-fantasy version of Toshiro Mifune's character in Yojimbo. The honorable ronin comes wandering into Jabba the Hutt's palace under a hood; once unhooded, he kills the Rancor and leaves Jabba's sail barge exploding over the sand dunes as he flies off in his X-wing to embark on other space-faring adventures.

In the same way that a person might eventually come to have their trust in authority figures shaken once they grow up and realize how flawed adults really are, Luke must next come to terms with Obi-Wan's white lie, that "certain point of view" BS he spouts as a justification for not revealing Luke's true parentage to him (though of course, this may have just been a clever retcon designed to tie up loose script ends, similar to the retcon of making Leia Luke's sister). With Master Yoda having faded into nothingness, Luke is now the last Jedi. In this guise, he goes to face the combined might of Vader and the Emperor on his own, embarking on a final pacifist suicide mission of sorts. Yet the Force is strong with Luke. He carries an inherent goodness with him, and in the end, however precariously, he does prove up to the task.

The ascension of Luke is sort of a meta-commentary on how geeks have inherited the Earth. If Luke can be seen, in some sense, as the young George Lucas, then by Return of the Jedi, Lucas had outgrown his mentors to become a self-made millionaire (later a billionaire). One of those mentors was Francis Ford Coppola, who took Lucas under his wing, only to wind up later being eclipsed by him. In the 1970s, a string of four cinematic achievements, The Godfather, The Conversation, The Godfather, Part II, and Apocalypse Now, crowned Coppola king of the decade. During this time, when he was still at the top of his game, Coppola's swagger is said to have inspired Han Solo's personality. But if you look at the turn Coppola's career took after Apocalypse Now — if you consider all the financial troubles he had in the years after — it is almost like he and Han Solo both followed the same track of peaking early.

In The Force Awakens, Solo reverts to roguish type as a debt-ridden space smuggler. Only now it is no longer cool because after all that happened, after all these years, Uncle Han doesn't outwardly show any real growth in the way he's living. That growth is there, of course, insofar as the guy who once said, "There's no mystical energy field controls my destiny," is now forced to confess, "It's true, all of it. The Force, the Jedi. It's all true."

It took him over 30 years, however, to get to a place where he was able to say that. In Return of the Jedi, Han Solo still had a long way to go. He was literally fumbling around blind from carbon sickness as events of larger importance played out around him. It had gotten to the point where even Harrison Ford was no longer interested in the character and was begging for him to be killed off, so that the character could have some meaning in death (which is why it was not all that surprising when Han died in The Force Awakens, since that was probably the only way they could get Ford to sign back on for the role in the first place).

Luke Skywalker: Surrogate Self to a Generation of Dreamers

When I was younger, Return of the Jedi was always my favorite Star Wars movie. I thought the ending wrung great pathos out of Luke's whole quest to redeem his father. Pre-Internet, pre-prequels, I could never understand why people compared it less favorably to the first two installments in the series. I have since come around to genuinely feel that The Empire Strikes Back is the best of the franchise, if not the single greatest motion picture ever made. Yet I also realize that I am now viewing the Star Wars movies through the prism of adulthood.

I can read interviews with people involved in the making of the original trilogy. I can note the departure of key collaborators Marcia Lucas and Gary Kurtz, and how that might have adversely affected Return of the Jedi's plot, particularly the part at the end involving an assault on "a new armored space station, even more powerful than the first dreaded Death Star." To be sure, the decision to end the trilogy this way had long-ranging implications, inasmuch as The Force Awakens recapitulated the same idea yet again with its derivative assault on the "thermal oscillator" of Starkiller Base, a.k.a. Even Bigger Death Star.

In a 2010 interview with Hero Complex, the pop culture arm of The Los Angeles Times, Gary Kurtz had this to say about the ending of Return of the Jedi:

We had an outline and George changed everything in it. Instead of bittersweet and poignant he wanted a euphoric ending with everybody happy. The original idea was that they would recover [the kidnapped] Han Solo in the early part of the story and that he would then die in the middle part of the film in a raid on an Imperial base. George then decided he didn't want any of the principals killed. By that time there were really big toy sales and that was a reason.

When I read quotes like this, I wonder what it would have been like if Return of the Jedi had given us "a more emotionally nuanced finale" to the first phase of the epic adventure that is Star Wars. No doubt the infusion of cute and cuddly Ewoks, however tactile those teddy bears might look, can be viewed historically as a foreshadowing of Binks to come. There are indeed hints laced throughout The Empire Strikes Back that the plot of Return of the Jedi could have followed a very different course. Based on some of the things Yoda says, turning to the Dark Side might have actually been a logical progression for Luke's character.

At the end of the day, however, I grew up with Luke Skywalker. He was the good guy. I came of age with him. That euphoric ending, the "teddy bear luau," nurtured my inner child. In college, it inspired my best friend and me to write mock-rock songs.

Really, if I had to cut out all the other noise and boil the essence of my pop culture love down to one thing, there would just be Luke and that inner child of mine.

Who knows? If they had killed off Han Solo and sent Luke "walking off alone like Clint Eastwood in the spaghetti westerns," my young mind might have developed differently. As it is, I grew up believing in things, thinking anything in this universe was possible because good had triumphed over evil and Luke and Leia, Han and Chewie, Lando and Artoo and Threepio all lived happily ever after, just like in a fairy tale. I think on some level I probably owe a large part of my youthful optimism to Star Wars.

There is now a whole new generation of fans who are probably having the same experience with Daisy Ridley's Rey. Rey's "hypercompetence" may have earned some criticism, but if you look at the Wikipedia definition for "Mary Sue," as quoted by Indiewire, it reads like something that could just as easily be talking about Luke Skywalker:

An idealized fictional character, a young or low-rank person who saves the day through extraordinary abilities. Often but not necessarily this character is recognized as an author insert and/or wish-fulfillment.

It remains to be seen how Luke's character will further evolve in The Last Jedi. In interviews, including one with our own Peter Sciretta, Mark Hamill has talked about how Star Wars is not his story anymore. George Lucas already tried to re-frame the Star Wars saga as Anakin Skywalker's story, only to succeed in showing how Anakin's story paralleled his own later artistic career. To paraphrase Obi-Wan Kenobi, the older Lucas "ceased to be Luke and became Anakin." Or, as one Reddit user put it, "George Lucas is Anakin Skywalker — the gifted young rebel whose fear of losing what he loved eventually led him to the Dark Side, down a path of good intentions."

Much has been made of how Star Wars follows the template outlined by Joseph Campbell for the Hero's Journey or "monomyth." When the Star Wars films finally came out on iTunes in 2015 and I re-watched them as a 33-year-old who had not seen them in several years, I was surprised by how they seemed to just tell this light adventure tale. I think part of what made them feel so much deeper to me when I was younger was because the story continued off-screen for me as I immersed myself in my own kind of expanded-universe mythology, acting out scenarios on the floor of my bedroom with a collection of action figures gathered from discount racks and garage sales back in the mid-1980s.

Luke Skywalker is a great character. On the eve of The Last Jedi, let's recognize his worth. This is a character who undergoes dramatic change, yet who is often unjustly dismissed by secular Star Wars fans (by which I mean those who are still on the fence about all this religious fan mumbo-jumbo, like Han Solo once was). As a vivid manifestation of the collective unconscious, whiny young Luke will outlive us all.

Whatever else he becomes in The Last Jedi, however sad, broken, or isolated he is, the Luke Skywalker of the original trilogy will always be the Hero With a Thousand Faces whose journey from innocence to experience — starting on the desert planet of Tatooine and ending on the forest moon of Endor — launched a multimedia empire of dreams. In his role as a protagonist, he is every kid or kid at heart who ever imbued Star Wars with his or her own flights of imagination: every toy collector, every comic book reader, every cosplayer, every dancing Stormtrooper, and yes, every mock-rock singer.

Luke Skywalker is the heart and soul of Star Wars.